Historical Background

The War of 1812: Military Stalemate and National Awakening (continued)

LAND CAMPAIGNS—BATTLE OF THE THAMES AND THE "ROCKET'S RED GLARE"

If the "War Hawks" and others wanted military action, they might have given thought to preparation for war. Its financing alone would be difficult. The Treasury was nearly empty, and Congress hesitated to enact new taxes. The First Bank of the United States had expired in 1811. Furthermore, the most prosperous section of the country, New England, opposed the war and would contribute as little as possible to its support.

In 1812 the Army consisted of 10 regiments, most of them on garrison duty in the West. Many of the ranking officers had seen no action since the War for Independence. To supplement the Regular Army, Congress authorized the recruitment of 25,000 5-year volunteers and 50,000 1-year militiamen. But the Army never achieved authorized strength, and for the most part it was inadequately supplied and poorly led.

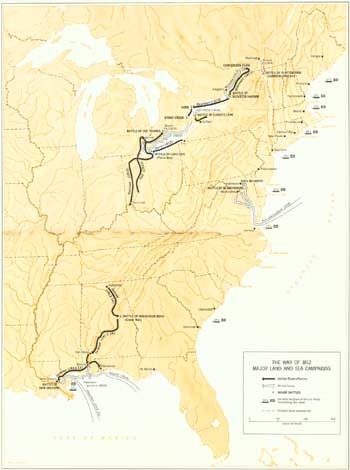

|

| The War of 1812 Major Land and Sea Campaigns (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

During the 2-1/2 years of the war, events seemed to conspire against the conquest of Canada by the United States. In 1812, before the United States could get an offensive underway, the British and their Indian supporters captured outposts at Detroit and Fort Dearborn (Chicago). The British had temporarily closed the western invasion route to Canada. To the eastward, the invasion of Canada went little better. Claiming that the terms of their enlistments did not require them to cross national boundaries, most State militiamen refused to join Regulars in thrusts across the Canadian border near Buffalo and over Lake Champlain toward Montreal.

The next year, 1813, gave the country some encouragement. William Henry Harrison, commander in the Northwest, with a small force endeavored to recapture Detroit, the gateway to western Canada. But he was unable to advance beyond Fort Meigs, near Toledo, as long as British ships controlled Lake Erie. Then, in September 1813, he received a message that began "We have met the enemy and they are ours." On September 10, 1813, a U.S. fleet commanded by the author of the message, 29-year-old Oliver Hazard Perry, had defeated a British squadron at the Battle of Lake Erie, near Put-in-Bay. Perry's victory forced the British to abandon Detroit and opened the way for Harrison's force to march into Canada.

|

| Artist's version of the Battle of the Thames (October 5, 1813), Canada, one of the major battles of the War of 1812, in which the Shawnee chief Tecumseh died. From a lithograph by John Dorival. Courtesy, Library of Congress. |

Harrison moved quickly. His army pursued the retreating British and Indians 100 miles into Canada to the Thames River, where they made their stand. The Battle of the Thames, in October of 1813, was a decisive defeat for the British in the Northwest. Among the battlefield dead was Tecumseh, leader of the Indian resistance to the advance of the frontier. Harrison's men had destroyed the British strength in the old Northwest and opened the way to settlement of lower Michigan and Illinois country. Elsewhere in 1813 the land war was indecisive. Gen. James Wilkinson, a veteran of the War for Independence, failed in his effort to capture Montreal.

|

| This cartoon, satirizing the Hartford Convention, depicts the Massachusetts delegate urging the Connecticut and Rhode Island representatives to leap into the arms of the King of England. At the Hartford Convention representatives of some of the New England States opposed U.S. participation in the War of 1812. From an etching by William Charles. Courtesy, Library of Congress. |

In 1814 the impending defeat of Napoleon in Europe allowed the British to turn more attention and divert materiel to the war with the United States. Red-coated British veterans, fresh from European triumphs, boarded transports bound for North America. The British planned to take the offensive. They would invade the United States from Canada. One force would drive southward over the Lake Champlain route and another cross the Niagara River into western New York State. An amphibious force would also attack the east coast of the United States and later seize New Orleans to gain control of the mouth of the Mississippi River.

By 1814 more than 1 year of war had hardened and improved the U.S. Army and permitted several excellent officers to rise to positions of command. Two of these were Gen. Jacob Jennings Brown and young Gen. Winfield Scott. They showed courage and talent in stopping the British invasion attempt in the Niagara region at the bloody Canadian battles of Chippewa and Lundy's Lane. To the east, the success of the British invasion over the Lake Champlain route required the capture of Plattsburgh, N.Y. There the 30-year-old Thomas Macdonough earned a place in the hall of naval heroes and the gratitude of the Nation by leading a hastily assembled flotilla of 14 ships against the British at the Battle of Plattsburgh (Cumberland) Bay, in September 1814. Macdonough's victory saved Plattsburgh and ruined the most promising opportunity of the British to invade the United States.

|

| James Madison, one of the authors of The Federalist Papers and fourth President. From a lithograph by John Pendleton, after a painting by Gilbert Stuart. Courtesy, Library of Congress. |

More spectacular, if less important to the outcome of the war, was the British diversionary raid in the Chesapeake Bay region of August and September 1814. By then ships of the Royal Navy were ranging along the entire east coast of the United States virtually at will. U.S. naval vessels, hopelessly outnumbered by the largest fleet in the world, remained helplessly blockaded in port.

In August the British repaid the Americans for the burning of York (Toronto), Canada, earlier in the war. A combined military and naval force entered Chesapeake Bay and sailed northeastward. The main force of soldiers and marines under Gen. Robert Ross left their ships at the mouth of the Patuxent River and marched overland toward Washington, D.C. The defenses of the Capital were inadequate. The British raiding force, about 3,000 men, easily defeated a makeshift defensive force at the Battle of Bladensburg, August 24. Of the 7,000 defenders of the Capital, only a few were Regulars. The latter gave a good account of themselves, especially a force of several hundred sailors, under Commodore Joshua Barney, who stymied the British advance for half an hour. But the sailors finally yielded, and the redcoats entered Washington. They set fire to the Capitol, White House, and other Government buildings. The Government had fled. A sudden rainstorm helped douse the fires but not before they had caused more than $1 million in damage. Then the British moved on to attack Baltimore.

|

| "The Taking of the City of Washington in America," a British version of their attack on Washington (August 1814). The letters indicate key actions. From a wood engraving by an unknown artist, published by G. Thompson. Courtesy, Library of Congress. |

The situation was different at Baltimore. The U.S. militia stood firm behind earthwork defenses south of the city, and the British attempt to flank the militia by water was met by the garrison of Fort McHenry at the entrance to Baltimore harbor. For 24 hours, on September 13 and 14, the British poured shot, shell, and rockets into the fort. Watching the bombardment from a U.S. truce ship detained by the British was a young Maryland lawyer, Francis Scott Key. As he watched, the giant American flag continued to wave above the fort. The British could not conquer Fort McHenry, and the attack on Baltimore failed; they moved back down the Patuxent, toward the sea. The defense of Baltimore helped to soften the humiliation of the burning of the Capital, and the bombardment of Fort McHenry gave the Nation "The Star-Spangled Banner."

|

| The British bombardment of Fort McHenry. From an aquatint by John Bower. Courtesy, Library of Congress. |

|

|

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/founders-frontiersmen/intro9.htm

Last Updated: 29-Aug-2005