Historical Background

The Spanish Conquistadors and Padres (continued)

THE FIRST INLAND PENETRATION

Cortés' one-time rival for command, Pánfilo de Narváez, made the first inland exploration in the area of the present United States. In 1526, he obtained title to all lands between the Rio de las Palmas and the Cape of Florida, and the next year left Spain. After stopping at Spanish bases at Santo Domingo and Cuba, in 1528 his expedition of 5 ships and more than 600 colonists, including friars and Negro slaves, landed on the west coast of Florida, probably in the region of Tampa Bay. Narváez split his command and sent his vessels along the shoreline while he led the main body of the expedition by land toward an intended rendezvous point up the coast. The two parties never met. The sea party missed the rendezvous and, after a futile search, returned to its home base.

Harassed by hostile Indians and scourged by privation and disease, the overland group struggled along the coast. Reaching the vicinity of Apalachicola Bay, the men, greatly reduced in numbers as well as strength, built crude rafts on which they courageously launched themselves westward toward Spanish settlements in Old Mexico. They sailed along the coast to Texas, where storms sank some of the rafts and drove others onto a low-lying, sandy island, probably Galveston Island. Thus began one of the most amazing adventures that has ever befallen any group of men.

The 80 or so survivors were so weak from starvation they could scarcely pull themselves out of the water. They scattered in small groups. Some wandered off and others joined the Indians; many died of hunger and disease. Winter hardships took more lives. The natives, at first friendly, turned belligerent and enslaved the remaining Europeans. Months of miserable captivity stretched out to 5 unbearable years.

Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, the treasurer and second officer of the Narváez party, obtained a reputation as a medicine man—his knowledge of medicine being a little more advanced than that of the Indians. In 1534, he and three others, including a Negro slave, Estévan, escaped and began an arduous 3-year trek across Texas and into Old Mexico that represented the first exploration by Europeans of any part of the present Southwestern United States. Their reports of great riches were to excite the imagination of men in the Viceroyalty of New Spain and stimulate exploration of the unknown area of New Mexico, to the north.

|

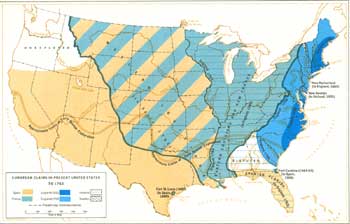

| European claims in present United States to 1763. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

TO THE MISSISSIPPI AND BEYOND

|

| Hernando de Soto led the fourth Spanish expedition to Florida. He explored much of the present Southeastern United States, and his survivors penetrated Texas. From an 18th-century engraving, probably conjectural. |

On her fourth expedition to "Florida," Spain scored a major success. Hernando de Soto and Luís de Moscoso, during the years 1539-43, explored extensively throughout the present Southeastern United States and obtained a wealth of information about the lands and peoples of the interior—beyond the Mississippi and as far west as Oklahoma and Texas. De Soto was perhaps the most determined and successful of all Spanish explorers. He had made a fortune as one of Pizarro's lieutenants in the conquest of Peru. As a further reward, Charles V granted him the right to conquer—at his own expense—the land of "Florida," which had not yielded to De León, De Ayllón, and Narváez before him.

In May 1539, De Soto and more than 600 men landed on the west coast of Florida. Marching north, they spent the winter of 1539-40 in the region of Apalachee, in the Florida Panhandle. In the spring, De Soto led his men northeast through present Georgia to the Savannah River. He then turned northwest, traversed part of South Carolina, fought his way through the mountains, circled back across northern Georgia and central Alabama, and in October reached the head of Mobile Bay.

There a severe battle with the Indians occurred, but the indefatigable De Soto would let nothing deter him. In a remarkable tribute to his leadership, after 18 months of fruitless wandering and the loss of more than 100 men to disease and Indians, De Soto's men continued to follow him when he turned his back on the sea and the outside world and plunged once more into the unknown continent. Moving northwest into present Mississippi, the explorer set up winter quarters.

In March 1541, Indians launched a sudden and catastrophic attack. Although they killed only 11 men, they burned the expedition's clothing and destroyed 50 horses and a large drove of swine. Though many of his followers were clad only in skins, De Soto resumed the march in a northwest direction and on May 8, 1541, discovered the Mississippi River. A month later, he crossed the swollen river on specially constructed barges and set out across present Arkansas. After several months of hard marching, the expedition may have penetrated as far as Oklahoma—at the same time as Coronado, who from a base in New Mexico had reached the same general region and was probably only 300 or 400 miles to the west. De Soto then turned back east and set up his third winter quarters, in southwestern Arkansas.

That spring the expedition started down the Mississippi—not to return home, but for the purpose of sending to Cuba for badly needed supplies. De Soto, however, sickened and died on May 21, 1542, and the men sank his body in the middle of the great river he had discovered so that the Indians would not find it and realize that he was mortal. Command devolved upon Luís de Moscoso, who promptly agreed with the men that it was time to abandon the wild venture.

The party decided to strike overland toward Spanish bases to the southwest rather than follow the Mississippi to the coast. Moscoso penetrated Texas, perhaps as far as the Trinity River, before becoming discouraged and returning to the Mississippi. Then, during the fourth winter, 1542-43, the men built small brigantines and prepared for a precarious voyage down the river and out into the gulf. They butchered and dried all the pigs and most of the remaining horses and filled barrels with fresh water. Liberating some 500 Indians whom they had enslaved, they embarked on July 2, 1543. Sixteen days later they floated out into the gulf, and on September 10 landed near Tampico. At the end of the amazing 4-year expedition, only half of the original members were still alive.

|

| Artist's rendition of De Soto at Tampa Bay, Florida, in 1539. From an engraving by James Smillie, after a drawing by Capt. S. Eastman. (Courtesy, Library of Congress.) |

THE SETTLEMENT OF FLORIDA

Four times had the Spanish Crown given patents to its bravest adelantados to conquer and settle Florida—De León, De Ayllón, Narváez, and De Soto. Each had lost his life in the attempt. But the importance of the Florida peninsula in controlling the Gulf of Mexico could not long be overlooked. Three more Spaniards were to make futile attempts to tame the region before a permanent settlement was at last accomplished.

In 1549, Friar Luís Cancer de Barbastro led a group of missionaries, supported by a few friendly Indians, from Vera Cruz to the vicinity of Tampa Bay, where hostile Indians massacred them. Only little more successful was the expedition of Tristán de Luna y Arellano a decade later from Vera Cruz to the Pensacola Bay area. It consisted of 1,500 colonists, soldiers, and friars, and 1 year's provisions. A hurricane nearly destroyed the fleet shortly after it landed; more than half the supplies were ruined; fever decimated the group; and the Indians, if not openly hostile, were zealous thieves. But some of the colonists survived. In 1561 Angel de Villafañe replaced De Luna, who proceeded to Havana. That same year Villafañe, at the direction of the Spanish authorities, set out to found a colony on the Carolina coast. After landing temporarily, probably at Port Royal Sound, in present South Carolina, and later at the mouth of the Santee River, the group sailed for Old Mexico by way of Pensacola Bay.

|

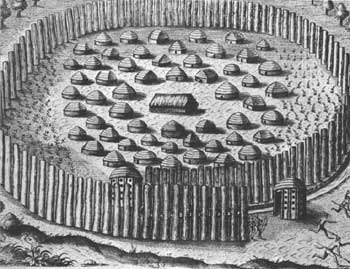

| A Florida Indian village. From a 1591 engraving by Theodore de Bry, after an on-the-scene drawing by Jacques le Moyne de Morgues. (Courtesy, Library of Congress.) |

The prospect of a permanent settlement in "Florida" must then have seemed remote to Spanish officials. But the establishment of French settlements there caused Spain to react with urgency. In 1562, Jean Ribaut and a small party of French Huguenots put ashore at Port Royal Sound to found the religious refuge that the farsighted Adm. Gaspard de Coligny was planning. Before the year ended, Ribaut abandoned the settlement, Charlesfort, but neither he nor Coligny was discouraged. In 1564, a second Huguenot expedition, under Rene de Laudonnière, landed at the mouth of the St. Johns River and erected a small stockade, Fort Caroline. Discipline soon broke down. Thirteen men stole the only vessel and set out to raid Spanish shipping in the Caribbean. Laudonnière immediately put the remainder of the men to constructing another vessel; when finished, it, too, was stolen by would-be buccaneers.

The French settlement aroused Spanish fury. Philip II, ruler of Spain and Europe's strongest monarch, allotted 600 troops and 3 ships to Pedro Menéndez de Avilés and ordered him to drive the Frenchmen out of his domain. Menéndez furnished a party of colonists and obtained De León's old patent to "Florida." Menéndez and his King were convinced that the Huguenot colony was intended as a base for French piracy. Ten years earlier, French pirates had sacked and burned Havana. Such a New World base as Laudonnière's could not be tolerated—and to add insult to the defenders of the Catholic faith, the Frenchmen were Protestant heretics. Late in August, Ribaut arrived from France with reinforcements.

On September 8, 1565, the Spaniards put ashore and began constructing a fort, around which grew the city of St. Augustine—the oldest permanent European settlement in the United States. Then, Menéndez marched northward and wiped out the settlers at Fort Caroline, which he renamed San Mateo. He next moved southward below St. Augustine, attacked a French party under Ribaut that had set out to fight the Spanish but had been shipwrecked, and put the few survivors to work constructing St. Augustine.

Despite the tireless energy of Menéndez, the Spanish colony in Florida grew slowly. From 1566 to 1571, determined Jesuit missionaries strove to bring Christianity to the reluctant natives in the region. They founded a number of small and temporary missions, but were not too successful in their overall effort. In 1566, they established San Felipe Orista on the Carolina coast, and a few years later may have reached as far north as Chesapeake Bay with other evanescent missions. After 1571, brown-robed Franciscan friars carried the word of God into the marshes and forests of the Florida region. At the height of their success, about 1635, they were ministering to thousands of neophytes at a number of tiny missions, mainly in the provinces of Guale, Timucua, and Apalachee, in northern Florida and coastal Georgia.

|

| This fanciful artist's rendition of St. Augustine, pioneer Spanish settlement, is of interest despite its historical inaccuracies. The Castillo de San Marcos at no time resembled the fort as portrayed. The artist probably included the high hills because he mistook the Spanish word for thick forests to mean hills. From the 1671 engraving "Pagus Hispanorum," by an unknown artist, probably prepared in Amsterdam. (Courtesy, Chicago Historical Society.) |

None of these missions proved to be permanent, and few of the "converted" Indians could actually be counted as Christians. When, in 1763, Spain surrendered Florida to England, little more than a feeble colony at St. Augustine evidenced two centuries of occupation. Besides the missions, two small outposts in the region called Apalachee, on the northwestern fringe of the peninsula, had been established to help supply St. Augustine: San Marcos de Apalache on the gulf coast, which originated in 1660 but was abandoned and reestablished several times thereafter; and San Luis de Apalache, a few miles north, the center of a temporarily flourishing mission field that was later relinquished during Queen Anne's War.

Over the years, Spanish Florida had suffered countless vicissitudes. In 1586, only 2 years before England ravaged Spain's mighty armada, Sir Francis Drake almost destroyed St. Augustine. Less than a century later, in 1668, another English force again nearly decimated it. Before many more years passed, British settlers from the Carolinas began a series of raids on the Spanish settlements in Florida. During Queen Anne's War, in 1702 the English captured and burned St. Augustine, although they failed to conquer the redoubtable Castillo de San Marcos, constructed in 1672. In 1704, Col. James Moore, attacking from the Carolinas, destroyed five mission settlements in Apalachee and later that year drove the Spanish out of the province. From then on, Spanish Florida was almost constantly in a state of war with the Carolinas and, after 1733, with Georgia. Attacks on St. Augustine by Gen. James Oglethorpe, the founder of Georgia, resulted in the construction of Fort Matanzas in 1743 as a part of Spain's last desperate effort to hold the region.

Even as British intrusion began to threaten Spanish Florida in the east, the French again encroached on the empire—this time in the west. To meet the threat of France's advance to the mouth of the Mississippi, the Spanish founded an impotent post—Fort San Carlos de Austria—at Pensacola in 1698 and undertook to settle Texas.

|

|

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/explorers-settlers/intro3.htm

Last Updated: 22-Mar-2005