|

Cowpens

Administrative History |

|

Chapter Four:

DEVELOPMENT OF COWPENS AS A NATIONAL BATTLEFIELD

Planning for Development Activities

In 1972 congressional legislation authorized Cowpens as a national battlefield of approximately 845 acres and appropriated funds for land acquisition and development. The National Park Service thus began the lengthy process necessary to devise suitable plans to govern the project's evolution. In the meantime, South Carolina's congressional delegation pushed through legislation increasing the development appropriations for Cowpens from $3.2 million to $5.1 million. By the late 1970s, the NPS was ready to begin work under the supervision of Kings Mountain Superintendent Mike Loveless, following plans devised during the mid-1970s. [1]

Unlike many NPS battlefields that were developed as parks by private organizations or the War Department before World War II, Cowpens presented NPS planners with a relatively clean slate for development according to the agency's post-Mission 66 design policies. Under the leadership of Director Hartzog in 1964, the NPS divided its parks into three categoriesnatural areas, historical areas, and recreational areas. Administrative policies were published for each of the three categories. As revised in 1968, the administrative policies for historical areas like Cowpens spelled out various park design principles, including land management classifications, preservation of historic structures, unobtrusive visitor centers away from historic features, roads that follow the natural contours, and one-way tour roads around the historic area's core. [2]

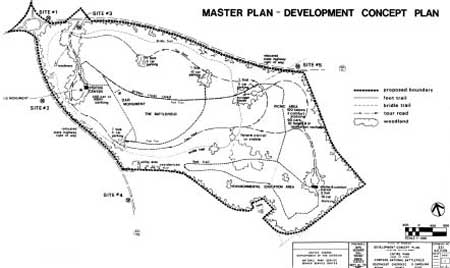

NPS planners at the Denver Service Center (DSC) produced the plans for Cowpens. The DSC plans divided the battlefield lands into three areas based on the categories in the 1968 NPS guidelines. The Class VI category for historic and cultural area lands included approximately 150 acres at the battlefield core, while Class II for general outdoor recreation lands included ninety acres. The plans classified the remaining 580 acres as Class III for natural environment area lands. The DSC plans called for an entrance road with a parking lot, a visitor center separated from the battlefield core, a walking tour trail, a one-way automobile loop tour road, a picnic area, an environmental study area, a bridle path, restoration of the Robert Scruggs House, preservation of the Richard Scruggs House Ruin, and a battlefield landscape restored to its 1781 appearance. Although planners had initially called for an observation deck or tower at the visitor center, cost considerations forced the abandonment of that idea. Before these facilities could be developed, the NPS had to remove post-battle manmade improvements and relocate Highways 11 and 110. The DSC finalized these plans in 1975. [3]

|

| Figure 11: A map of proposed developments at Cowpens from the 1975 Master Plan. |

Land Acquisition and Project

Staffing

Even though the NPS planning delayed development at Cowpens, the land acquisition program proceeded. The Service ironed out the details of relocating residents from the area, including schedules, compensatory payments, relocation allowances, arrangements for relocating houses, and condemnation procedures. Stationed at Cowpens, Realty Specialist Henry Hilliard oversaw land acquisition until September 1974 when the Southeast Regional Office took over the process. By October 1979 all land within the authorized boundary except for two acres had been acquired by the NPS. Most residents cooperated with the NPS in the land acquisition and relocation process, although some did so grudgingly. [4] As one local stated, "What are you gonna [sic] do when the government says move?" [5] Two more serious controversies arose, however, with owners of tracts included within the authorized park boundary.

One dispute involved thirty-five acres owned by the Daniel Morgan Rural Community Water District. The district argued that the property was necessary for a future water tower. In addition, the Farmers Home Administration within the U.S. Department of Agriculture held bonds that had financed the construction of the water district's infrastructure. The district expressed concern that it would be unable to repay the bonds because of the revenue loss created by the park's displacement of customers. Facing lengthy condemnation procedures and a negative image in the community, NPS officials sought a compromise solution to the dispute. After a March 1976 meeting between Kings Mountain Superintendent Moomaw, a representative of the regional solicitor's office, and attorneys for the water district, a compromise solution began to take shape. As part of the deal, the district agreed to exchange its thirty-five acres for a small NPS tract appropriate for use as a water tower site. An August meeting determined the location of the property to be deeded to the water district. In February 1977 the property exchange took place with the district acquiring half an acre on the southern perimeter of the park near the relocated Highway 110. [6]

Another problematic land acquisition effort involved a two-acre tract belonging to New Pleasant Baptist Church. The congregation voted against selling the property on several occasions. Although the NPS had originally viewed the land as a necessary buffer for the Richard Scruggs House Ruin, Loveless decided that the property was not essential and designated it as an inholding in 1979. The church property, the water district tract, and the highway rights-of-way remain the only non-NPS holdings within the authorized park boundary. [7]

With the Service ready to begin developing Cowpens, the first full-time staff members on site reported for duty in January 1978. Administrative offices were located in a house near the original NPS site. To head up the on-site staff, the NPS stationed Patricia Stanek at Cowpens as the unit manager reporting directly to Superintendent Loveless. Stanek held degrees in communications and psychology, and her early background was in the development of a school curriculum media and environmental education. Stanek had also served in the Southeast Regional Office as an environmental education specialist and interpretive planner. During the development process, she oversaw park operations and later served as the first superintendent of an independent Cowpens NB. [8]

|

| Figure 12: This house served as a temporary visitor center at Cowpens during the park's development |

Physical Development of the National

Battlefield

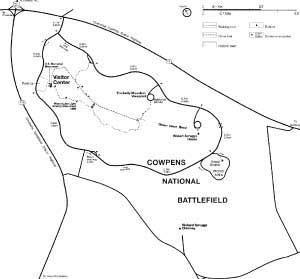

Between 1978 and 1981, the NPS developed the national battlefield at Cowpens in three phases. The first phase involved relocation of Highways 11 and 110, clearance of all intrusions from the battlefield, relocation of the U.S. Monument, construction of an entrance road and parking lot, and installation of an automobile tour road and a walking tour trail. The contract for this phase was awarded to Champion Landscaping and Excavating Company of nearby Kings Mountain, North Carolina. [9]

Between October 1978 and September 1979, the first development phase was gradually completed. After relocating Highways 11 and 110 around the park, Champion removed manmade intrusions on the battlefield, including the old highway beds, water mains, buildings, and other structural remains. Workers relocated three houses to the periphery of the battlefield for park use. Under subcontract to Champion, the firm of Trotino and Brown disassembled the U.S. Monument piece-by-piece and reassembled it at the site of the planned visitor center. The contractor constructed a parking lot at the visitor center site and an entrance road connecting the parking lot to the new Highway 11. Workers built and paved the one-mile interpretive walking trail through the battlefield core area. The trail included ten wayside exhibits and seven audio units with recorded messages. In addition, Champion completed the interpretive loop road around the core area with overlooks and exhibits at the Robert Scruggs House and two areas of the battlefield. With the completion of the first phase, the NPS had removed the post-battle developments and established the layout of the new park. [10]

|

| Figure 13: The new interpretive walking trail at the battlefield, 1979 |

|

| Figure 14: The U.S. Monument being disassembled in preparation for relocation to the new visitor center site |

|

| Figure 15: The groundbreaking ceremony for the visitor center, October 29, 1979. The woman with the shovel is Edith Fort Wolfe, a NSDAR supporter of Cowpens since the 1930s. To her left holding shovels are South Carolina Representatives Bryan Dun and Sam Manning and Congressmen James Mann and Ken Holland |

The second development phase involved the construction of a visitor center to house the park's museum, visitor facilities, and administrative offices. Initial DSC plans were rejected by the regional director as too large, expensive, and wasteful of energy. The revised plans called for a smaller visitor center with a price tag of $425,000 rather than the original $950,000. The building was to include museum exhibit space, a meeting room for presentations, and administrative offices. The DSC designed the low profile building to blend in with the landscape and conserve energy. This design reflected both the NPS planning emphasis on unobtrusive visitor centers and the federal government's energy concerns in the wake of the 1970s energy crisis. With plans finalized, the NPS awarded the visitor center contract to the Spartanburg firm of Christman and Parsons Construction Company. The final cost of the visitor center was $457,855, or less than half of the amount assessed for the original plan. [11]

The NPS held a groundbreaking ceremony for the new visitor center on October 29, 1979. The brief event attracted South Carolina politicians, including Manning and Congressmen William J. Bryan, Kenneth L. Holland, and James Mann. In addition, the list of participants included Edith Fort Wolfe, the local NSDAR member who had been lobbying for the Cowpens expansion since the 1930s. The NPS performed its final inspection of the completed visitor center on October 21, 1980, nearly a year after ground was broken. [12]

The third development phase at Cowpens involved the construction of picnic and maintenance areas. Located off the interpretive loop road, the new picnic area had one covered shelter. The NPS completed the maintenance building and surrounding parking lot on the periphery of the park near the relocated Highway 110. Last, workers placed the utility lines underground to remove the visually intrusive above-ground lines. By the beginning of 1981, the development program at Cowpens was essentially complete. [13]

The Youth Conservation Corps

As part of the Cowpens development process, the NPS undertook projects through the Youth Conservation Corps (YCC). Created by congressional legislation during the Nixon Administration in 1970, the YCC was a program that employed teenagers during the summer to work on outdoor projects at properties administered by the Departments of the Interior and Agriculture. Reminiscent of the Civilian Conservation Corps that contributed greatly to the development of national parks during the Great Depression, the YCC allowed various national parks, national forests, and national wildlife refuges to undertake physical improvements. [14]

During each summer from 1978 to 1980, around two dozen YCC enrollees worked at Cowpens. The participants were local teenagers hired to work on park projects for thirty hours a week. In addition, enrollees spent ten hours a week engaged in environmental education through classes and field trips. The park's YCC projects included removing fences, clearing peach orchards, filling wells, laying gravel, planting, cleaning dump areas, digging drainage ditches, and constructing nature trails. Park staff estimated that the cost of these projects would have doubled without the YCC program. [15]

Besides the economic benefits, Cowpens staff recognized the value of the YCC program as a public relations tool. The park recruited participants each spring through schools, churches, and libraries in nearby Cherokee and Spartanburg Counties. After seeing the battlefield's operations first hand, the enrollees usually became strong supporters of the park's mission as well as potential future seasonal staff. According to Stanek, the public relations impact of the YCC was "its greatest achievementover 24 per annum newly created ambassadors opening doors that previously had been shut." [16]

|

| Figure 16: Map of Cowpens NB as developed by 1981 |

Plans for an Environmental Study Area and A Living

History Farm

When the development of Cowpens was completed in 1981, the park still lacked two interpretive facilities originally called for by park planners in the 1970san environmental study area and a living history farm. Both of these planned areas resulted from new directions in NPS interpretation during the 1960s. Across the land environmental issues had begun to receive significant attention, especially after passage of the National Environmental Policy Act in 1969, a landmark in federal legislation. Within the NPS, policy leaders showed an increased interest in developing environmental study areas at parks to educate the public on the environment. Between 1968 and 1975, the Service took up the cause of environmental education by creating an office of environmental education at the Washington headquarters, developing environmental study areas at eighty parks, and initiating programs for schools, interpreter training, and urban outreach. The establishment of environmental study areas extended beyond the natural parks to include historical parks like battlefields. [17]

An environmental study area was envisioned as an important interpretive facility at Cowpens from the earliest planning stages. Furthermore, Stanek had an extensive background and interest in environmental education. DSC planners envisioned an environmental study site near the park's picnic area. This facility was to include a parking lot, a shelter, restrooms, and trails through the surrounding wooded areas. School groups were to be the primary users of the site, and the main interpretive focus was to be the natural environment of the South Carolina backcountry at the time of the battle. [18]

In the end, however, the environmental study area failed to materialize. The primary obstacle was fundingthe park could not afford the facility and the accompanying interpretive staff to support it. In addition, environmental education within the NPS lost momentum. The notion of historical parks educating the public on environmental issues had always been controversial. By the early 1980s, NPS Director Russell E. Dickenson was steering interpretive programs away from environmental education, especially at the historical parks. In the end, the interpretive programs and visitor facilities at Cowpens focused on the 1781 battle, colonial life in the backcountry, and general recreation. [19]

The second planned interpretive facility that failed to develop was a living history farm. Like environmental education, living history first became popular during the mid-1960s under Director Hartzog. In addition to military weapon demonstrations and encampments, NPS living history programs involved operating farms. By 1968 over forty parks included living history components in their interpretive programs. Within this context the 1970 master plan and the 1973 interpretive prospectus recommended a living history farm to emphasize the fact that the site was a "cowpens" at the time of the battle. Unfortunately, cost considerations forced the DSC to drop the farm concept from its development plans in 1975. Likewise, the bridle path and the horse rental concession appeared in both planning documents but were not developed due to limited congressional appropriations. Nevertheless, living history programs involving military demonstrations have been a constant part of the park's interpretive program. [20]

National Battlefield Dedication and Independence

from Kings Mountain

The new park facilities at Cowpens were dedicated during the two hundredth anniversary of the battle on Saturday, January 17, 1981. NPS Director Russell E. Dickenson attended the formal dedication ceremony. Nearly a decade after Congress authorized the national battlefield, the NPS had developed Cowpens into a full-scale unit of the national park system. Recognizing this fact, as of March 22 the regional director removed Cowpens from the administration of Kings Mountain and placed Stanek in the superintendent's position. With development of the battlefield completed, the NPS focused on managing the park's resources and interpreting the story of Cowpens to the public. [21]

|

| Figure 17: The stage during the dedication ceremony for Cowpens NB, January 17, 1981. Among the many political dignitaries are NPS Director Russell Dickinson, fourth from the left, and Kings Mountain Superintendent Andrew M. Loveless, in uniform |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

http://www.nps.gov/cowp/adhi/adhi4.htm

Last Updated: 10-Dec-2002