|

Colorado

A Classic Western Quarrel: A History of the Road Controversy at Colorado National Monument |

|

CHAPTER FOUR:

Construction of Rim Rock Drive: 1931-1950 (continued)

The Road Project and the Community (continued)

In the meantime, Congressman Taylor received a telegram on December 15 from Robert N. Moreland, the father of one of the accident victims. Moreland requested another investigation, which Taylor assured him had been ordered by the Park Service. [344] E.B. Rogers, then superintendent of Rocky Mountain National Park, carried out the second investigation. On December 21, he met with local officials, including the chamber of commerce, the district attorney, the county certifying officer for CWA, and workers in the park. He concluded that the community generally agreed that the accident was unavoidable and that local residents still had faith in Secrest's abilities as supervisor of the road project. The workmen, however, were critical of W. Liddle, the foreman in charge of the workers involved in the accident, and C. E. McEwan, the explosives foreman. Finally, Rogers concluded that the controversy about the accident had been needlessly kept alive by people who were not directly involved in the incident, and that for the most part, the situation was finally settling down. [345]

The Half-Tunnel accident established a lasting connection between the road project and surrounding communities. Because only local men were killed, the accident was an especially sensitive issue. Nevertheless, the accident indicated that local interest in the park was still strong, and that the Park Service considered community support of the road project necessary. Congressman Taylor's intervention on behalf of Robert Moreland, which resulted in a second investigation, was a sign that public support of the road project was considered important to higher level officials. In the second investigation, E.B. Rogers emphasized the importance of community opinion as well. While his report included interviews with workmen, it was primarily an effort to measure the community's support of the road project. Finally, two editorials appearing in the Daily Sentinel expressed sympathy toward the victims' families, but also highlighted the road project's economic importance to the Grand Valley. [346] Ultimately, the Half-Tunnel accident was another example of the role that the community played in the Colorado National Monument's development. Because of nine local deaths and years of interest and money invested in the park, the people were naturally affected by the first major fatality on the road project. As the years passed, however, and Park Service road policy changed, many local residents pointed to the half-tunnel to indicate the sacrifice the community made for the road.

The availability of labor was an important gauge of local perceptions of the road project as well. Local employment levels varied. The original rosters for CCC camps 824 and 825 reveal that the majority of workers were from outside Colorado. The National Park Service was allowed to employ a certain percentage of LEMs, whose principal task was to train new enrollees. In 1934, restrictions were relaxed on the amount of LEMs hired. [347] Local men were also hired by relief groups other than the CCC. In December 1933, for instance, 50 unemployed men from Glade Park were hired by a federal civil works program to work on the road project. [348] Nevertheless, it is not clear just what percentage of workers in the Colorado National Monument was from the local area.

The community often panicked when projects were temporarily stopped due to lack of finding. Throughout the years of heavy construction, layoffs were common. In January 1934, for instance, there were 816 unemployed with 2100 dependents in Mesa County. The labor bureau urged the park to hire more workers despite already filled quotas. The park certainly could have used more labor but was not able to enroll any more men. [349] In March 1935, the closing of a Public Works project in the park put 165 men out of work. When families poured into the area from the dust-ravaged areas in Kansas and Nebraska, the already critical unemployment situation in the Grand Valley worsened. [350] The temporary closing of a CCC camp and a PWA camp in April 1935 prompted daily inquiries from local men seeking employment. Eventually 26 former employees of the camps went to the local relief office to convince officials to continue funding for the projects. [351] It is not clear if this appeal was successful, but it indicates that the local economic situation was such that the community relied upon the road project.

Roosevelt's attempt to make a permanent agency of the ECW in 1935 resulted in the closure of camps and reduction of enrollees in the Colorado National Monument and other parks. In September 1935, Roosevelt instructed ECW director Robert Fechner to reduce the ECW from its peak enrollment of 600,000 to 300,000 men by June 1936. In May 1936, he instructed the National Park Service to reduce its state and National Park camps by 20, and the number of enrollees per camp from 200 to 160. [352] Enrollment levels in CCC camps at Colorado National Monument averaged 160 as early as March 1936, and the custodian reported that "work projects suffered, because of the low company strength." [353]

Roosevelt continued his push for a smaller, permanent agency in January 1937 when he presented his annual budget message to Congress. He eventually hoped to decrease the ECW to 300,000 men and war veterans, 10,000 Native Americans, and 7,000 from U.S. territories. Congressional input was necessary because the ECW had only been authorized until June 1937. Roosevelt again pitched for a permanent agency in March 1937; under this plan the CCC would be an independent agency, new employees would be subject to Civil Service guidelines, and enrollees would be between the ages of 17 and 23 with evidence of proven need. Instead of creating a permanent agency, however, Congress passed a bill in which the ECW officially became the CCC and was extended until 1940. Despite the obvious changes in his plans for the CCC, Roosevelt signed the bill. [354]

This bill signaled a turning point for the CCC. Cuts in the program continued through 1937 and 1938. As more camps closed, officials in Washington received complaints from park superintendents who felt that certain projects and necessary park functions were interrupted and postponed. A measure to stabilize the CCC passed both the House and the Senate in 1938. In an effort to prevent the closure of 300 camps, $50 million was allotted to work relief programs. In addition, the number of National Park camps increased to 77 and state programs increased to 245. [355] Even after this effort, the CCC increasingly lost its effectiveness. By the time the U.S. entered World War II, its termination was inevitable.

|

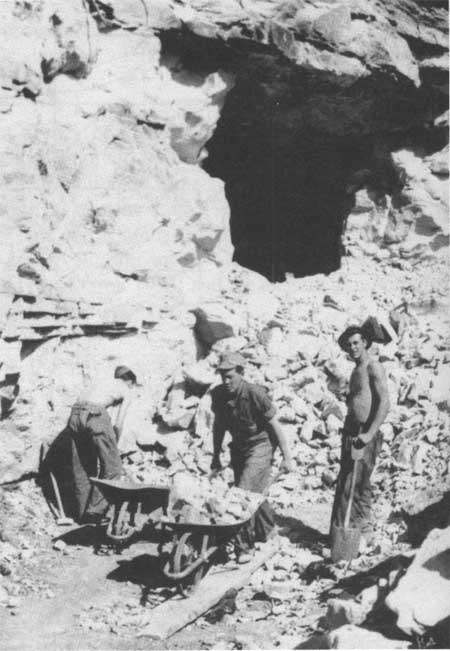

| Figure 4.10. Workers remove blast rubble from coyote hole or pilot bore in one of the road's three tunnels. Colorado National Monument Museum and Archive Collection. |

|

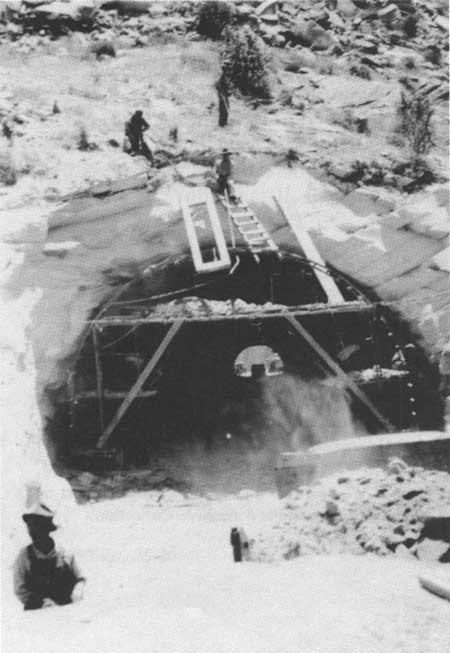

| Figure 4.11. North portal of tunnel #3 on east Rim Rock Drive. Colorado National Monument Museum and Archive Collection. |

Despite the uncertainty of the CCC's future, work camps in the Colorado National Monument accomplished a great deal. The years from 1937 to 1942 reflected not only the problems associated with labor cuts, but also the effectiveness that the work camps were capable of displaying. By June 7, 1937, 20 miles of Rim Rock Drive, including two tunnels, were opened for visitor use. [356] Numerous other projects were completed as well. The work camps built visitor facilities, an employee residence, and planned an administration area. Acting custodian Jesse Nusbaum commented in his monthly report for the park that "Colorado National Monument is beginning to shape up and looks more like a monument should. There is a far better spirit of cooperation between all agencies working on the Monument." [357]

Nevertheless, once the attack on Pearl Harbor occurred on December 7, 1941, work strength in the CCC decreased as national defense needs increased. In February 1942, all CCC projects were terminated but were picked up by the WPA until June 1942, when construction in the camp ended. Even the custodian and rangers at the park were called to active duty. [358]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

colm/adhi/adhi1-4d.htm

Last Updated: 09-Feb-2005