|

Chesapeake and Ohio Canal

The Making of a Park |

|

CHAPTER SIX:

EXPANDING THE PARK

The 1971 act finally gave the National Park Service the authority and means—with subsequent appropriations—to enlarge its narrow canal right-of-way into a viable park. Land acquisition was the primary purpose of the legislation and became the first priority following its enactment.

The act did not inaugurate Park Service real estate dealings along the canal, however. There had been some previous additions in the three decades since the railroad had conveyed the canal. There had also been moves to alienate some of what the Service had then acquired.

Cumberland, it will be recalled, had tried to obtain the canal property within the city limits in 1941 (page 53). Once the Service became committed to the parkway concept, it was willing to relinquish portions of this property in exchange for other lands fulfilling its needs.

In September 1953, at the request of Sen. J. Glenn Beall, Associate Superintendent Harry T. Thompson of National Capital Parks met in Cumberland with representatives of its chamber of commerce, the Maryland State Roads Commission, and Pittsburgh Plate Glass. PPG was planning a plant in the Mexico Farms area and wanted part of the canal property for a railroad siding. "The essence of the conference was to the effect that the National Park Service would cooperate fully with the Cumberland Chamber of Commerce and with the industrial firm since the canal proper between Lock 75 for a distance of approximately 1-1/2 miles upstream . . . was scheduled for abandonment as a canal, and that we would encourage the Chamber of Commerce to proceed on the assumption that all of the land between the Western Maryland Railroad and the river might be made available to the industrial plant and that the National Park Service would endeavor to locate the parkway eastward of the B & O Railroad tracks," Thompson reported. [1]

Previously, du Pont had decided against locating a plant near Hagerstown, citing complications in getting access to needed river water from the Park Service. This public relations fiasco, as Thompson characterized it, figured in Hagerstown's opposition to the parkway. Thompson's eagerness to cooperate with Cumberland and PPG was designed to demonstrate that the parkway would not impede Maryland's economic development. [2]

By the time the Corps of Engineers' Cumberland-Ridgely flood control project got underway in the mid-1950s, the Park Service had essentially written off the canal above Lock 75 (the last lift lock) at North Branch. The Corps was permitted to fill in the last mile of the canal and a former basin used as a ballpark and obliterate the inlet lock at the terminus. The Western Maryland Railway extended track across the terminus site, and a new connection between the Western Maryland and B & O railroads further altered the scene. Remaining portions of the canal in Cumberland were silted, overgrown, and laden with raw sewage; Robert C. Horne of NCP described conditions there as "frightful" in a 1956 inspection report. [3] The first national historical park bills, drafted by the Service soon afterward, provided for the disposal of canal lands above North Branch in exchange for lands desired elsewhere.

The B & O Railroad was interested in a land exchange because it had built some of its track in Cumberland on canal property and had neglected to reserve those sections when the government acquired the canal in 1938. The Park Service was most interested in obtaining an acre of B & O land in Harpers Ferry where the fire engine house occupied by John Brown and his raiders had stood. It also wanted B & O parcels totaling 25 acres at or near Tuscarora, Point of Rocks, and Knoxville, including some of the land that the railroad had reserved for additional trackage. [4]

The railroad would not part with the latter, but negotiations proceeded on the Cumberland and Harpers Ferry tracts. When the park bills containing the necessary land exchange authority stalled, Senator Beall inserted an exchange provision in pending legislation adding the Storer College property to Harpers Ferry National Monument: "To facilitate the acquisition of the original site of the engine house known as John Brown's 'Fort' and the old Federal arsenal, the Secretary of the Interior is hereby authorized to exchange therefor federally owned park lands or interests in lands of approximately equal value in the vicinity of Cumberland, Maryland, which he finds are no longer required for park purposes." [5]

This legislation was enacted without difficulty on July 14, 1960, but the exchange negotiations faltered thereafter. The B & O wanted all the canal property above North Branch and sought to replace a railroad bridge over the canal between Locks 73 and 74 with fill that would sever the canal. In June 1962 Director Conrad L. Wirth responded with the Park Service's position. The terminus of park development would be at Lock 75; therefore, the railroad would not be permitted to sever the canal below that point. The Service would require additional land from the B & O for its park development at North Branch, and it was unwilling to cede all its land above that point to the railroad, preferring to transfer or lease land not needed for actual railroad development to Cumberland or Allegany County for recreation. [6]

Competing requests for canal property in Cumberland and the B & O's merger with the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad led to another hiatus in negotiations. They resumed in 1965 but soon encountered further obstacles. Richard L. Stanton of the NPS Lands Division discovered what he termed a fraudulent appraisal equating the value of the lands to be exchanged. As reappraised by Stanton, the property to be given the railroad was worth far more than that to be received by the government. In November 1966 John M. Kauffmann, a chief planner for what would become the Potomac National River proposal, discouraged alienation of canal land above North Branch because of its expected role in that project. The Park Service was now willing to quitclaim only those lands actually occupied by the railroad (three sections totaling about 15 acres) in exchange for the engine house site, while the railroad continued to press for additional canal lands for its future expansion. By 1969 the negotiations had again reached an impasse. [7]

That January the Service exchanged the ballpark tract in Cumberland, comprising 16.2 acres, for 183.55 acres of Maryland land under State Roads Commission jurisdiction. With Rep. Charles McC. Mathias's support, Cumberland had sought the ballpark tract for industrial development since 1964. The Service stalled on this request because its negotiations with the B & O for Cumberland lands had priority; meanwhile, the SRC encroached upon the tract for an approach to the Cumberland Thruway. This led to its exchange in 1969 for land the SRC had acquired for Interstate 70 between Great Tonoloway Creek and Millstone. [8]

Efforts to acquire a 338-acre tract between the canal and MacArthur Boulevard below Great Falls got underway in 1958. This Maryland Gold Mine tract, so called from the name of a gold mine there sporadically active from 1867 to 1940, lay within the authorized jurisdiction of the George Washington Memorial Parkway. The parkway road was still expected to extend to Great Falls, and the tract was needed for the purpose. In addition, the U.S. Geological Survey, with the support of the Park Service and the National Capital Planning Commission, planned to use part of the tract for a new headquarters and research center. [9]

The Service sought a donation from Paul Mellon's Old Dominion Foundation to acquire the tract in 1959, but that effort failed. In 1964 Margaret Johnson, the owner, sold it to Herman Greenberg's Community Builders, Inc. Greenberg applied for rezoning to develop the property, whose value had increased with the construction of the Potomac Interceptor Sewer through it. The Service began purchase negotiations; when agreement could not be reached, the government condemned the tract on July 14, 1965, and was assessed $2,012,111 for it by the court. [10]

The government did not use the tract as planned. The parkway road was not built beyond a junction with MacArthur Boulevard more than a mile to the east. The Geological Survey headquarters proposal was successfully opposed by the Civic League of Brookmont, Maryland, and Rep. Henry S. Reuss of Wisconsin, who noted that the national capital area's Policies Plan for the Year 2000 prescribed such development in corridors away from the Potomac. [11] (The Geological Survey subsequently built in Reston, Virginia.) The undeveloped tract was included within the George Washington Memorial Parkway and remained there after establishment of the C & O Canal National Historical Park, but it has been managed as part of the latter in practice.

Along much of the canal, the uncertain status of boundaries and land titles severely impeded park management. The C & O Canal National Monument (above Seneca) had more than three hundred miles of boundary, of which less than a third had been surveyed and even less had been marked. "This has given rise to an untenable situation with respect to management, development and use of canal lands, and has allowed encroachments, trespass and overlapping claims to land ownership to continue at the expense of our public image and in defiance of our public responsibilities," Superintendent W. Dean McClanahan complained in 1967. [12]

McClanahan was especially concerned about the lack of title data. "In spite of 29 years of public ownership, we still do not know exactly what the Federal Government's rights, titles and interests in and to these lands actually amount to," he noted. "In some instances there is real doubt that the Government has sufficient title to adequately administer or even claim ownership to various tracts of land that are essential to provide continuity of public access and use." [13] Above Dam 4 where the towpath ran along the riverbank, for example, riverside properties owned by William B. McMahon and Jacob Berkson were unencumbered by recorded deeds to the canal company. In the absence of land acquisition authority above the George Washington Memorial Parkway limits, however, title searches or litigation that might bolster private claims to canal lands had low priority. Resolution of boundary and title issues awaited enactment of the national historical park legislation.

On December 23, 1970, a day after the Senate cleared the legislation for the President's signature, Dick Stanton, then chief of the Office of Land Acquisition in the Park Service's Eastern Service Center, outlined an acquisition strategy for the park: "Except for approved development areas, we do not feel that there should be any roadblocks to an orderly, scheduled land acquisition program. It should simply begin on either end of the 184-mile strip and proceed up or down the canal. The title, access, and squatter problems will be systematically eliminated through direct purchase acquisition or condemnation. . . . One of the matters which the Directorate feels very strongly about, is to absolutely avoid any tendency to buy out of priority by serving special interest groups or individuals who, through some means or other, manage to create a great deal of heat." [14]

Following enactment of the park legislation, the Park Service's legislative office held an "activation meeting" on January 25, 1971, to identify responsibilities and procedures for implementing it. Land acquisition was a major topic. The legislation required that "the exact boundaries of the park" be established and announced within 18 months. Because a metes and bounds description could not be completed that soon, it was decided to depict the boundary on portfolios of tax maps to be filed with the land records of the affected counties by May 1. Stanton's office would draft letters for NCP General Superintendent Russell E. Dickenson to send to each landowner on the berm (inland) side of the canal indicating generally what part of his or her land fell within the boundary. Dickenson would tell Stanton's office what interest was desired in each tract (fee simple or easement) and which purchases were of highest priority. Stanton agreed to set up a lands office in the area by May 1. [15] George W. Sandberg, appointed land acquisition officer, found quarters at Fort Detrick in Frederick, Maryland.

That September the Park Service informed Maryland's congressional delegation of its acquisition policy and plan for the canal. Of 47 planned developments, 34 would need additional private lands. These lands would be purchased in fee, with the owners allowed to retain occupancy pending development. All lands between the canal and river (except those containing public utility plants) would be purchased in fee; here improved residential property owners could retain 25-year or life tenancies and clubs could retain rights for 25 years. Farmlands between the canal and river could be retained for a period of years or leased back for agricultural purposes; compatible commercial properties could be leased back under special use permits.

Owners on the berm side would be given the option of fee or easement purchase. Easements would restrict their properties to their present uses or low-density residential development removed from the canal, flood plains, and steep slopes. Where there was less than a hundred feet of public ownership on the berm side, the Park Service would seek sufficient interest in adjacent private land to permit public access and the maintenance of screening vegetation. The Service hoped to protect about 25 percent of the private lands within the authorized park boundary by less-than-fee interests. [16]

Land acquisition did not move as swiftly and methodically as hoped. Progress was slowed by difficulties with a mapping contract and public opposition to the many development areas in the park's master plan that were to receive priority. The proposed level of development was sharply criticized by the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park Commission after it was organized in December 1971; as a result, the master plan was scrapped and a major new planning effort inaugurated. Affected landowners were not notified until the spring of 1972. When acquisition finally began thereafter, it proceeded on an "opportunity purchase" basis: land was bought first from those who were eager to sell. [17]

Some thought purchases should continue to be made only from willing sellers. At a public meeting on the new park plan in Brunswick in June 1972, landowner John Staub of Dargan Bend argued that the Park Service should take better care of what it had before taking property from those who wanted to keep it. "What we don't approve of is dealing with our federal government on a take it or leave it basis, bargaining, so to speak, with a gun at our heads or our backs. . .," he said. "We don't like the idea, and we do not intend to kiss the boot that kicks us from our land." [18]

Previously, Mary Miltenberger, a park commission member from Allegany County, had proposed that counties be encouraged to set up historic districts along the canal to control development and thereby lessen the need for land acquisition. Goodloe E. Byron, western Maryland's congressman, introduced a bill incorporating both viewpoints in April 1972. It would suspend the government's power to condemn improved properties for the park where local authorities had approved protective zoning satisfactory to the secretary of the interior. [19] The Park Service opposed this "Cape Cod formula" (so called from its initial use at Cape Cod National Seashore) on the canal, fearing that it could prevent the acquisition of lands needed for park development. Byron's bill made no progress then or in the next Congress, after which he dropped it.

Tropical storm Agnes, which devastated the canal soon after the Brunswick meeting, had a positive effect on the land acquisition program: those who were flooded out were less inclined to resist the government's purchase offers. By the end of 1972 acquisition was well underway. The Service had then identified 1,009 private tracts totaling 11,513 acres and had purchased 104 of them totaling 1,732 acres for $2,494,819. John G. Parsons, an NCP planner who was leading the new park planning effort, played a key role in deciding what property interests should be acquired based on projected park development, topography, existing uses, and other such criteria. [20]

Dick Stanton, now associate director for cooperative activities at NCP and Parsons' boss, helped resolve many policy issues as they arose. It was decided that the Service would not purchase land up to the authorized boundary if doing so would entail major severance costs and meet no real need. Properties between the canal and river would be appraised as if their owners had legal access across the canal, but the NPS reserved the right to adjust such access for the benefit of the park where the owners retained occupancy or use. Properties accessible only via the towpath would be acquired without retained rights to avoid vehicular use of the towpath. [21]

Riverfront land acquisition was complicated by the uncertainty of ownership between the high and low water lines. The government sought to purchase to the low line, but title companies would only insure private sellers' titles to the high line because of possible claims by Maryland beyond that point. To resolve the problem, Stanton arranged to have sellers warrant titles to lands above the high line and quitclaim titles below. The Service would thereby control the intervening strip unless a court later decided that Maryland owned to the high line, in which case the state might be persuaded to donate its holding. [22]

The NCP lands division set terms for all scenic easement acquisitions in September 1972. On lands subject to scenic easements, only permanent single-family residences could be constructed and occupied, although camping vehicles were permissible for temporary occupation. No new structure could rise more than forty feet or be built on slopes steeper than twenty percent. Except for basement excavations and footings, wells and septic facilities, and required road construction, no change in the character of the topography or disturbance of natural features would be allowed. There could be no cutting of non-hazardous trees larger than six inches in diameter at breast height. There could be no "accumulation of any trash or foreign material which is unsightly or offensive" and no signs exceeding certain specifications. All existing buildings could be maintained; if damaged or destroyed, they could be rebuilt or replaced in the same locations after approval of plans by the secretary of the interior or his designee if they were at least two hundred feet from the inland edge of the canal prism. [23]

Certain of these and other easement terms were amended and interpreted in the light of experience. Mrs. Drew Pearson's house in Potomac was less than a hundred feet from the canal prism. She was permitted to replace an appurtenant structure there in February 1973, and a general policy of reviewing such requests was adopted. At the same time, swimming pools and patios were added to the list of allowable improvements. [24]

Easements were often difficult to enforce. Edwin M. ("Mac") Dale, canal superintendent from 1957 through 1965, had worked on the Blue Ridge Parkway, where the Park Service had pioneered this method of land-use control. "Don't ever get involved with scenic easements—they are a snare and a delusion," he later told Dick Stanton. "You either own it or you don't." William R. Failor, superintendent from 1972 to 1981, found it hard to educate his staff about easement terms and limits and to maintain sufficient contact with landowners, especially new ones, to remind them of restrictions. [25]

Enforcement of the tree cutting restriction was especially difficult. As Failor admitted, many owners violated it with impunity over the years. Ultimately, one went too far. In March 1985 park rangers discovered that 134 trees had been cut down on government property in fee ownership and adjoining property covered by a scenic easement in Potomac. The latter belonged to Isaac Fogel, who had hired a tree service to improve his view of the river. Fogel was indicted in August 1988 and convicted in February 1989 on two counts: aiding and abetting the conversion and disposition of United States property, and aiding and abetting the removal of timber. He was fined $25,000, sentenced to 3-1/2 years in prison (all but 15 days in a halfway house was suspended), and made to perform three hundred hours of community service. [26] The conviction was important for its deterrent effect on others who might be tempted by the high premium on riverview properties in Potomac to follow Fogel's example.

The land acquisition program proceeded vigorously through the mid 1970s, with the occasional protests common to government takings of private property. The owners of a subdivision lot on Praether's Neck (the area within the large riverbend bypassed by Four Locks) complained to Representative Byron in October 1973 about the Service's "land grab." They had been told that they had to sell and could rent back for only two years thereafter, whereas the Potomac Fish and Game Club below Williamsport would be allowed to remain for 25 years. NCP Director Manus J. (Jack) Fish, Jr., explained that continued residence in the subdivision would be incompatible with Park Service plans for restoration of the historic scene and a visitor use and environmental study area. In acting on the park legislation, he noted, Congress had favored special consideration for sportsmen's clubs, most of which were removed from planned visitor facilities. [27]

In November 1974 Maryland's two U.S. senators wrote the secretary of the interior to urge that 25-year leasebacks negotiated thereafter contain an option for an additional 25-year period at fair market rental. The primary intended beneficiary was the Potomac Fish and Game Club, with which negotiations were about to begin. Acting Secretary John C. Whitaker replied that the granting of such options would be unfair to previous sellers and would unduly impede future park management. He promised that the government would be liberal with Potomac Fish and Game: while limiting it to 25 years on the river side of the canal, the Park Service would acquire only a scenic easement on the club's inland property. Dissatisfied, the club again brought its considerable influence to bear, with the result that acquisition of its riverside property was deferred "for lack of funds" in October 1975. Ultimately, Dick Stanton concluded an agreement with the club in 1986 whereby the Service would not acquire the riverside property as long as the club did not increase its development. [28]

Whites Ferry, near Poolesville, became another exception to the policy of acquiring fee title to all land between the canal and the river. The proprietors of the ferry, the last on the Potomac, indicated that they would leave if the Park Service took the 2.62-acre tract containing the operation, and the Service had no desire to go into the ferry business. "I really feel that the best thing we could do on Whites Ferry would be just to bypass the whole proposition," Stanton told John Parsons in 1976. "The public is being served and we always have the option at some later date to buy the land if the ferry is discontinued or a bridge built by the State." Acquisition of the ferry tract was not pursued. The operators had an informal arrangement with the Service beginning in 1975: they maintained one of their two picnic areas, for which they charged a fee, on canal property; in return, they mowed the grass and picked up trash along the canal. The Service formalized this arrangement in a special use permit in the mid-1980s, when the operators built a large picnic pavilion on park property. [29]

The park's annual report for 1975 described the land acquisition program as "near completion." As of that May, 1,205 tracts had been identified for fee or easement acquisition, of which only ninety remained to be negotiated. Condemnation proceedings were underway on 189 tracts. About a quarter of these were "friendly" condemnations to clear titles; the rest were forced by owners holding out for higher prices or better occupancy or easement terms than the government was willing to offer. [30]

By the end of 1977 the Park Service had spent the $20.4 million authorized for land acquisition in the 1971 park act and obtained most of the lands and interests that it had planned to acquire under the act. It then held 12,640 acres in fee and scenic easements on another 1,164 acres, for a total of 13,804 acres. Not included was most of Praether's Neck, which remains the largest privately held area between the canal and river within the authorized park boundary. A small but critical exclusion was 2,200 linear feet of towpath along the slackwater above Dam 4 claimed by Jacob Berkson, owner of the adjoining property. After protracted negotiations, Berkson finally donated the strip for tax purposes in 1986. [31]

|

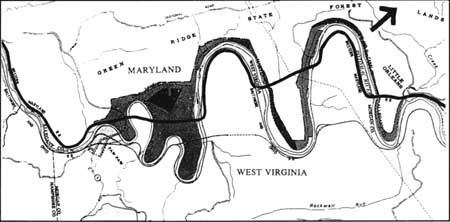

| The Western Maryland Railway in West Virginia. |

A significant addition to the park beyond the boundary authorized in 1971 was a 34-mile stretch of the Western Maryland Railway between Woodmont and North Branch. The merger of the Western Maryland with the parallel B & O Railroad in the Chessie System eliminated the need for this stretch, and the Interstate Commerce Commission approved its abandonment in February 1975. About four miles of the abandoned section, which traversed the sweeping Potomac bends below Paw Paw, West Virginia, lay within the park boundary—in places directly alongside the canal. Six of the remaining thirty miles lay in West Virginia, in three discrete segments reached by six Potomac bridges. Three tunnels, one nearly a mile long, cut through mountain ridges on the Maryland side of the bends.

The Park Service wanted the abandoned right-of-way primarily to prevent private parties from acquiring and developing it. It could also be used for a scenic bicycle trail, and parts of it would enable better access by patrol and maintenance vehicles to isolated portions of the towpath. The Service obtained authority to acquire the right-of-way in the omnibus National Parks and Recreation Act of 1978, which revised the park boundary "to include approximately 600 additional acres" and authorized another $8 million for land acquisition—enough for other outstanding purchases as well as the right-of-way, which the Service had appraised at $650,000. [32]

The legislation did not specifically mention the Western Maryland Railway or expansion of the park into West Virginia, where opposition to federal acquisition had been instrumental in blocking the Potomac National River. Riverfront landowners and officials in Morgan County, West Virginia, did not become fully aware of the Service's plans until 1980, when final purchase negotiations were underway with the railroad. They were not pleased.

Jack Fish, regional director of the Service's National Capital Region (as the National Capital Parks office was retitled in 1975), attempted to mollify them at a meeting of the Morgan County Commission that August. He claimed that the Service was acquiring the West Virginia segments of the right-of-way only because of the railroad's desire to sell the abandoned route in toto. (In fact, the Service had never sought less than the entire stretch.) Two landowners voiced concern about people crossing the railroad bridges from Maryland and trespassing on private lands. Another feared that the government would be able to condemn existing crossing easements over the right-of-way, thereby acquiring effective control of lands between it and the river. Viewing the acquisition as an entree to the Potomac National River—never officially dropped—they were not satisfied by Fish's promise to barricade the bridges, "mothball" the West Virginia segments, allow present access across them by adjoining owners to continue, and work toward their management by the state or county under a cooperative agreement.

Dayton Casto, a county leader, summed up local feelings about the Service's acquisition plan: "Let me tell you, it was the best kept secret since the atom bomb. . . . This thing didn't come up until just the last three months that we have known. . . . You have the Park Service over in Hancock saying we're going to make a hiker-biker across here, and then you are saying you are going to mothball it. Now which one do we believe? You say you are not going to get any more land, and yet you have an official position that says you are preparing legislation on the Potomac National River. These things are confusing us and making us unhappy." [33]

Under continued political pressure, the Service was forced to agree to relinquish fee title to the West Virginia segments to adjoining owners. When it acquired the right-of-way from the railroad on January 2, 1981, the deed and payment for the West Virginia segments were placed in escrow for ninety days, during which it negotiated terms with the owners. But the Service placed restrictions on what could be done with the land and required that all of it be conveyed simultaneously. The owners were unable to act in concert, and the Service took title on April 1. Thereafter it offered special use permits to the owners, under terms that none found sufficiently advantageous to accept. The Service barricaded the bridges, making them difficult but not impossible to cross; a proposal to remove them in 1983 after one person was killed and another badly injured in falls was not seriously pursued. [34] The 34-mile right-of-way, although overgrown, remains intact, requiring only several millions in federal funds and a revolution in West Virginia attitudes to fulfill its outstanding potential for a scenic bikeway.

Nearly a decade after the Western Maryland acquisition, the Park Service obtained another railroad right-of-way at the other end of the canal. The B & O's Georgetown Branch discontinued service in May 1985 when its last customer, the General Service Administration's West Heating Plant in Georgetown, shifted to delivery of coal by truck. The line ran along the river side of the canal from Key Bridge west to its bridge over the canal and Canal Road near Arizona Avenue, thence along the heights above the canal en route to Bethesda and Silver Spring, Maryland. There was much discussion of using the Bethesda-Silver Spring segment for light rail passenger service and some thought of extending this to Georgetown, but most interested parties favored only a hiking and biking trail for the Bethesda-Georgetown segment.

As with the Western Maryland, the Service was eager to acquire the right-of-way along the canal to prevent its private acquisition and development and to install a paved bicycle trail, which would be especially valuable here to separate bicycle traffic from pedestrians on the heavily used towpath just above Georgetown. Working with the Service and the National Park Foundation, Kingdon Gould III, a wealthy Washington businessman, bought the Washington portion of the right-of-way for $11 million in November 1989. Having obtained $4 million for the acquisition in fiscal 1990, the Service and the foundation arranged to lease the right-of-way from Gould until Congress appropriated another $7 million the following year. On November 20, 1990, Gould transferred 4.3 miles of the line totaling some 34 acres to the Service. [35]

The park boundary legislated in 1971 authorized no land acquisition beyond North Branch, some eight miles below the historic canal terminus in Cumberland. The Service's prior decision to terminate park development at North Branch, the extent of residential and industrial development on lands bordering the canal property beyond that point, and the recurring pressures from the railroad and Cumberland interests to cede rather than enlarge park holdings made this decision a logical one.

Mary Miltenberger, one of Allegany County's two representatives on the park commission, did not agree. At the commission's first meeting in December 1971, she complained that the Service's plan to make North Branch the western gateway to the park would deprive Cumberland of much-needed tourist income. With her encouragement, Cumberland's city council passed a resolution in May 1972 favoring a boundary expansion above North Branch, a position endorsed by the park commission that July. That December Maryland's U.S. senators, J. Glenn Beall, Jr., and Charles McC. Mathias, Jr., held a hearing on the matter at Allegany Community College. Those present were generally supportive. [36]

In December 1973 Senators Beall and Mathias and Gilbert Gude, Montgomery County's representative in Congress, introduced legislation to include within the park boundary above North Branch an additional 1,200 acres, of which not more than half could be acquired in fee. The bills also directed a visitor center to be established at or near the canal terminus; the Western Maryland Railway station there was envisioned to serve this purpose. But Goodloe Byron, western Maryland's congressman, declined to cosponsor the legislation without assurance that all affected landowners were in agreement—a virtual impossibility. [37]

Asked to comment on the legislation in August 1974, Jack Fish avoided taking an explicit position but called attention to the developed nature of the area in question, implicitly questioning its suitability for addition to the park. He suggested a study of the proposal by an outside planning group that did not share NCP's ties to the expansion proponents. In response, Russell Dickenson, then NPS deputy director acting for the Service, recommended against the expansion bills while expressing support for a study authorization. Although Beall and Mathias reintroduced their bill in July 1975, Congress never moved further to expand or study expansion of the park above North Branch. [38]

The Chessie System still wanted title to at least those canal lands in Cumberland occupied by its tracks, and the Park Service still wanted the railroad's property at Harpers Ferry where the engine house occupied by John Brown had stood. Negotiations resumed in 1986 with Chessie's successor, the CSX Corporation. As of 1991, the Service was willing to transfer four tracts used by the railroad totaling 15.04 acres and grant a perpetual easement for the railroad's bridge over the canal at North Branch. In return, it sought all of the historic U.S. Armory site at Harpers Ferry, including the land occupied by the existing railroad station. A controversial proposal for a new parkway along the canal in Cumberland that would use part of the land involved there complicated matters somewhat, but the exchange authorized by Congress in 1960 appeared closer than it had for some time. [39]

At the end of 1990, the boundary of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park encompassed 19,237 acres. The Park Service held fee title to 12,713 acres and scenic easements on 1,356 acres, for a total of 14,069 acres under its ownership or control. The state of Maryland and other public jurisdictions held another 2,528 acres, much of it in Green Ridge State Forest and Fort Frederick and Seneca Creek state parks. The balance, 2,640 acres, remained in private hands. [40]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

choh/history/history6.htm

Last Updated: 11-Oct-2004