|

Chesapeake and Ohio Canal

The Making of a Park |

|

CHAPTER TEN:

USING THE PARK

A park, according to standard dictionary definitions, is a tract of land set aside for public recreational use. This primary purpose is what distinguishes parks from other land reservations, such as wildlife refuges, set aside primarily for the protection of particular resources. This is not to say that other reservations cannot also accommodate recreational use, and it is certainly not to say that parks need not protect resources. The language of the 1916 act of Congress creating the National Park Service still obtains: the Service is to conserve park features and provide for their enjoyment by the public "in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations." While not for everyone doing everything they wish everywhere at every time, parks are indeed for people.

The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal served public recreation long before it became a park. At the beginning of the century the McMillan Commission noted its use "by pleasure seekers in canoes, and by excursion parties in various craft." In 1934, a year after the Park Service assumed responsibility for the national capital park system, a Service historian reconnoitering the canal reported considerable recreational activity: "The canal towpath is much used by hikers. On weekends, at any season of the year, people may be seen singly and in groups walking along the canal, particularly between Great Falls and Washington." [1]

|

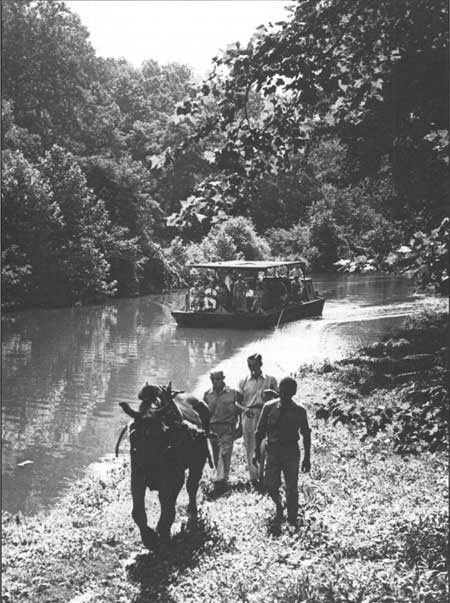

| The first Canal Clipper. |

Recreational use there surged after the Park Service acquired the canal in 1938 and restored and rewatered the portion below Seneca. The damage from the 1942 flood and the closing of the canal in the Great Falls area during World War II sharply curtailed towpath traffic, which was never high along most of the canal. Service leaders saw the lack of public use above Seneca as a threat to the canal's viability as a park in the face of conflicting development pressures. This concern figured heavily in the 1950 parkway proposal.

The highly publicized hike led by Justice William O. Douglas in 1954 to mobilize opposition to the parkway succeeded both in achieving that goal and in stimulating more of the public to follow the hikers' example. After the Service dropped the canal parkway scheme in 1956 and sought to win support for national historical park legislation, it did much more to improve the towpath for hikers and cyclists and provide recreational facilities along the way. These improvements enabled the park to capitalize on the soaring public interest in backpacking, bicycling, and physical fitness during the next decade.

The canal helped launch this movement, still with us, in early 1963. On February 9, a month after President John F. Kennedy established the President's Council on Physical Fitness and challenged Americans to become more physically active, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy set out from Great Falls at 4 a.m. and hiked fifty miles in 17 hours. He took the towpath as far as Point of Rocks, then headed inland toward Camp David. (Four other administration officials fell by the wayside.) The attorney general's feat attracted much notice, and a fifty-mile-hike craze swept the country. In later years other government notables would exercise regularly on the towpath. President Jimmy Carter ran once or twice a week from Fletcher's Boathouse to Lock 5 and back. Vice President George Bush, sometimes joined by Barbara Bush and their dog, often ran from Lock 10 down to Lock 6 in the mid-1980s. [2]

The C & O Canal Association, an outgrowth of the C & O Canal Committee formed at the end of the Douglas hike, was organized in 1956 as a general membership group open to all with an interest in the canal. Under its aegis, Douglas led a one-day hike along a section of the towpath each spring to generate support for the park legislation. Association-sponsored commemorative hikes continued after 1971. On the twentieth anniversary in 1974 and every five years thereafter, participants have gone the full length of the canal. Justice Sandra Day O'Connor kicked off the 35th anniversary hike, completed by 29 participants, in 1989. [3]

Orville Crowder, one of the canal association's early leaders, hiked the towpath with a measuring wheel to help position mileposts and locate features in canal company records. Crowder established the association's level walker program, wherein members volunteer to walk prescribed levels or other segments of the canal at least twice a year to collect minor trash and report other deficiencies and conditions to the association and the park superintendent. Following tropical storm Agnes in 1972, the level walkers, then led by Thomas F. Hahn, helped report the flood damage. The level walker program has continued active in the early 1990s under the leadership of Karen M. Gray, an association vice president.

Members of the C & O Canal Association, the Friends of Great Falls Tavern, and other park users have donated time and effort in many more ways. In 1990, 961 volunteers contributed 7,256 hours of service to the park. They cut brush, cleared vegetation from historic structures, picked up litter, led nature walks, staffed information desks, and presented musical programs during special events. The Girl Scouts' weekend interpretation of 19th-century canal life at Rileys Lock, led by Joan Paull, was sufficiently popular with participants and visitors to be repeated at the historic Knode house at Lock 38.

Mule-drawn barge trips have catered to the more typical park user. Canal Clipper, operated by the Welfare and Recreational Association, began service in Georgetown in July 1941. As many as eighty passengers boarded the barge above Lock 3, rose through Lock 4, and traveled as far as Lock 5 before returning. Canal Clipper was replaced in the spring of 1961 by the larger John Quincy Adams, holding up to 125 people and featuring a snack bar, built and operated by GSI (Government Services Inc., successor to the Welfare and Recreational Association). It lasted only eleven years, being destroyed by Agnes in 1972.

A second Canal Clipper built of reinforced concrete was launched in Georgetown in the fall of 1976. During the 1977 season (May through October) it made 305 trips and carried 17,751 passengers. Prolonged canal repairs in Georgetown beginning in 1979 prompted its relocation to Great Falls. There it succeeded the small John Quincy Adams II, which had operated from 1967 through the early 1970s. The Morris and Gwendolyn Cafritz Foundation donated $180,000 for a new Georgetown barge, launched in September 1982 after completion of the repairs there. Georgetown, as it was christened, and the second Canal Clipper remain in service at this writing. Both are operated by the Park Service, which charges fees to make them self-sustaining. The two barges carried 35,974 visitors in 1990, 16,190 in Georgetown and 19,784 at Great Falls.

The barges became excellent vehicles for interpreting canal history. Standard narrative talks ultimately gave way to "living history" presentations in which costumed employees reenact 19th-century life on the canal. Of course, no description of how a lock worked can match the first hand experience of floating from one level to another.

Yet another boat materialized at the other end of the canal in the mid-1970s. With the encouragement of the park, a private group called C & O Canal, Cumberland, Inc., began raising funds in 1973 for a 93-foot boat. A naval reserve unit prefabricated it the next year at the Allegany County Vocational-Technical Center. It was intended to float on a rewatered section of the canal between Candoc and Wiley Ford, but when the prospect of rewatering that section dimmed, the sponsors completed its assembly on private land opposite Lock 75 at North Branch, where rewatering appeared more likely. The Cumberland was dedicated there on July 11, 1976. The park later acquired the land on which the boat sat and issued a special use permit to C & O Canal, Cumberland, for its "operation." Rewatering never occurred and the boat remained high and dry (after holes were drilled in its bottom to drain collected water). The Cumberland has nevertheless served a useful interpretive purpose, for it more nearly approximates a historic canal packet than do the floating barges downstream. It is the centerpiece of "Canal Days," an annual festival sponsored by C & O Canal, Cumberland.

In 1973 the park opened a small visitor center in Hancock. In 1985 it acquired space in the former Western Maryland Railway Station in Cumberland, close by the buried canal terminus. Both visitor facilities received good historical exhibits and have been effective dispensers of information to upper canal users.

Park visitors have been served by several concessions. GSI (now Guest Services Inc.) operated the Georgetown barge until 1972. It continues to rent canoes, boats, and bicycles at the Harry T. Thompson Boat Center, next to the canal tidelock at the mouth of Rock Creek, and it operates a food concession at Great Falls. Fletcher's Boathouse, between the canal and river above Georgetown, has long rented canoes, boats, and bicycles to park patrons. So has the Swain family at Swains Lock, the next above Great Falls. The Parks and History Association, a nonprofit cooperating association serving most National Capital Region parks, sells publications and other park-related items at the Georgetown, Great Falls, Hancock, and Cumberland visitor centers. The proceeds help support park interpretation and other visitor services.

The Park Service works hard to compile visitor statistics, which help buttress requests for funds and staff by showing how many people are using the parks. The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park poses a major challenge in this regard, for its elongated nature and abundance of uncontrolled access points make accurate counts impossible. The park's counting method in the mid-1980s resulted in figures of 4,900,841 total visits in 1986 and 6,048,335 in 1987. The method was then revised, producing presumably more realistic figures of 2,074,721 in 1988, 1,991,207 in 1989, and 1,965,828 in 1990. (All figures are for visits rather than individual visitors, who may be counted repeatedly as they appear at different times and in different places.)

Whatever the totals, there is no doubt about the continuing disparity of public use within the park. In 1990 the Palisades District, extending only one-sixth of the park's length, counted 1,499,028 visits—more than three quarters of the total. Palisades had 48,360 visits per mile (concentrated most heavily in Georgetown and at Great Falls), while the rest of the park had 3,030 visits per mile. Although some might wish for a more equitable dispersion of visitors, this pattern is to be expected given Palisades' relationship to the Washington metropolitan area and the special scenic and recreational appeal of the canal's restored section. And for those seeking a different kind of park experience, the relative solitude of the upper canal is highly desirable.

A few visitors travel the full length of the canal, using the hiker-biker campgrounds en route. More travel over extended distances, some of them also camping for a night or two. Other campground users are drawn primarily by the river's recreational opportunities. The park recorded 42,998 overnight stays by such visitors in 1990. Of course, the great majority of visitors come for less than a day at a time to walk, cycle, fish, boat or canoe, watch birds, and otherwise enjoy small segments of the park.

All of them, from the casual day-tripper to the full-length tramper, are beneficiaries of an extraordinary public commitment to preserve 184 miles of canal and riverfront in largely undeveloped condition. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Justice Douglas played key roles leading to this outcome, as did farsighted members of Congress, Interior Department officials, and conservation groups. Like most great things, the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park was achieved only with great effort. Recalling the opposition and envisioning what might have befallen Maryland's Potomac riverbank, Gilbert Gude, who sponsored the successful park bill in the House, still marvels at the park's existence. Others involved with the struggle and those who just enjoy this special place today might well echo Gude's assessment: "Amazing." [4]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

choh/history/history10.htm

Last Updated: 11-Oct-2004