|

Capitol Reef

Cultural Landscape Report |

|

HISTORY (continued)

| |

|

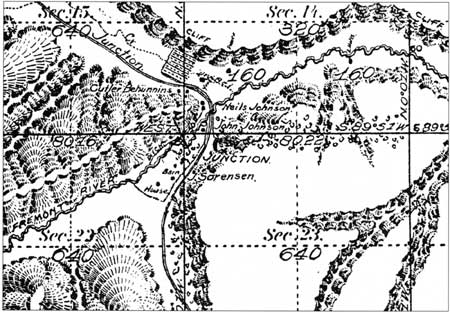

Fruita Township Map, 1896, showing small

settlement of Junction. Including roads, buildings, orchards, fences,

and an early irrigation ditch. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) | |

MORMON SETTLEMENT AND EARLY AGRICULTURE, 1880-1920

Under the leadership of Brigham Young, members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter day Saints (LDS) immigrated to the valley of the Great Salt Lake beginning in 1847. In the following years, Young laid down the principles that would govern the development of new settlements established by LDS members, referred to as "Saints" or "Mormons." A land system was established based on the principle that the welfare of the social group transcended that of the individual. The methods employed to allot land and water represented a high degree of cooperation, rare among most other frontier settlements. The Mormons' achievements in desert agriculture enabled permanent settlement of the Great Basin and subsequent expansion into surrounding territories. By 1870 the most desirable areas of the Mormon region were occupied, and only marginal niches remained to be settled. Mormons then expanded out from the St. George-Salt Lake "corridor" into the Colorado Plateau country to the east. In south-central Utah. this movement of peoples occurred after 1875 when large herds of horses and cattle were driven to Rabbit Valley, about 30 miles west of the Waterpocket Fold. The ranching communities of Fremont, Loa, Lyman, Bicknell, Teasdale, Grover, and Torrey developed on the high plateau just west of present-day Capitol Reef National Park (CARE).

Mormon occupation of the Capitol Reef area followed the pattern of prehistoric peoples, clustering in the river valleys. Located at the confluence of the Fremont River and Sulphur Creek, and first called "Junction," the Fruita area was first occupied by Mormon settlers in the early 1880s. A few early arrivals claimed squatter's rights, selling their land within a few years after their arrival. Between 1897 and 1904, four individuals, Nels Johnson, Leo R. Holt, Elijah Cutler Behunin, and Hyrum Behunin (Elijah's son), filed on, and received title to, homesteads in the area, claiming virtually all its arable land. [1] The first homestead title of 160 acres was granted to Nels Johnson in 1897. In his final affidavit, Johnson stated that he constructed a house in 1886 at the junction of the two watercourses, taking up residence at the site in 1887. In 1888, he began cultivating 17 acres, 7 of which were in orchards. In an 1896 affidavit, Johnson stated that his property included 3 one-room houses, a granary, a corral, and 100 rods (1,650 feet) of fencing. Johnson also noted that the property was most valuable for the production of fruit. The Homestead Act final proof papers indicate that at least 11 acres of Johnson's land were planted in orchards by 1901.

| |

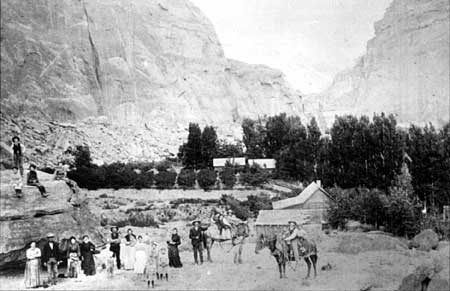

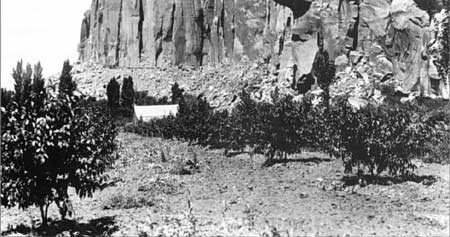

| View of the Holt Farm, showing small orchard and garden looking east, ca. 1890s. | |

Less than a year after taking title to his homestead, Johnson and his wife, Mary, sold more than 37 acres to Susannah Pendleton, wife of Calvin (Cal) D. Pendleton, who resided on the property at the time of sale. The same year they sold 6 acres to Amasa E. Pierce and more than 24 acres to Johnson's father-in-law, Elijah C. Behunin. The 1896 Fruita Township Map shows that J. Sorensen had built a house and barn on the southern portion of Nels Johnson's homestead.

Just west of Johnson's claim, Elijah Behunin settled his 120-acre homestead claim in 1893. [2] Two years later he had approximately 12 acres in cultivation, 4 of which were devoted to orchards. His son, Hyrum, established residency to the south on another 120-acre claim in 1895 and, beginning in 1896, cultivated 35 acres. Like other residents, Hyrum Behunin noted his land was valuable chiefly for farming and raising fruit. By 1904, when he received title., his claim was completely fenced and included a lumber house, corral, stable, and undefined outhouses.

Along the Fremont River east of Johnson's land, Leo R. Holt took title to 120 acres in 1899. Holt did not provide detailed information on his homestead in testimony and affidavits. He and his wife, Anna Laurina (Rena), apparently settled in Junction about 1892-1893. Nearly six months before receiving title to the property, Holt sold more than half of the homestead acreage to Amasa E. Pierce (27 acres) and H. J. Wilson (38 acres). Amasa E. Pierce would become the presiding elder in Fruita for the Mormon Church after the turn of the century.

| |

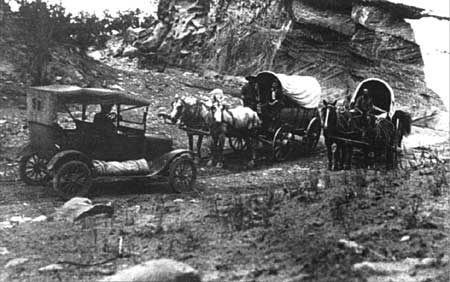

| Automobile and horse-drawn wagons confront each other on the narrow road through Capitol Gorge. (undated) | |

In 1883 a wagon road was cleared through Capitol Gorge by early residents to provide a link to other settlements downstream. The road was later extended to Hanksville. Known as the "Blue Dugway," it served as the primary route through the region until 1962. This route was used by ranchers to move sheep and cattle between winter pastures in the northeast and southeast of the Fremont River valley and summer pastures in the higher plateaus to the west. Livestock production assumed increasing importance in the Utah Territory in the 1880s and 1890s, particularly in those areas with marginal value as farmlands. Most farms in Fruita included a small number of horses, mules, and either cattle or sheep, or both. Crops were grown in the valley bottoms while livestock were grazed on the surrounding hillsides.

By 1900, 46 individuals (14 adults and 32 children) lived in the Junction Precinct. School-age children attended a log schoolhouse that was completed in 1896. Because Fruita had no church building, its devout settlers attended "sacrament meetings" (holy communion) in private homes or in the schoolhouse, presided over by the visiting bishop from Torrey. With the establishment of a post office about 1900, residents of the valley were required to give up the name "Junction," which was already held by another town. In recognition of the importance of the valley's orchards, the name of the community was changed to "Fruita." Fruita's location in a sheltered valley with a milder climate than the surrounding area encouraged the cultivation of fruit trees, vineyards, and certain types of garden produce (such as tomatoes) that were difficult or impossible to grow in the plateau towns of higher elevation to the west and deserts to the east. Fruit orchards in particular comprised a unique feature of the local landscape. Fruit was in high demand within the local economy and could be sold for cash or bartered for supplies not produced in Fruita. Vineyards were valued for providing grapes for wine-making and all fruit was prized as a trade commodity, sometimes used to acquire grains from the upland areas to produce distilled liquor (clandestinely). The sale of wine and grain-based hard liquor provided a significant source of income for some of Fruita's residents. [3]

Virtually all cultivation in Fruita required irrigation. Farmers used the field-ditch system of irrigation, with ditches painstakingly redug or cleaned annually. Field-ditch flooding was labor intensive, requiring cooperation between families to divert water from the two water courses to fields and orchards that varied in average total size from about 90 to 110 acres during the historic period. [4] The fact that seven or eight families were able to divert water from two streams at several different points and deliver it to such a large acreage of fields and orchards is testimony to the effectiveness of the Mormon cooperative ideal and the importance of water in the arid landscape.

From its initial settlement, floods were troublesome to residents of Fruita, as well as to the downriver settlements of Aldridge, Caineville, Blue Valley (Giles), Clifton, and Elephant. Because Fruita stood a little higher along a more deeply incised watercourse, the damage was not usually as heavy as in some of these other towns. Mrs. Evangeline Godby of Caineville recalled the flood of 1909:

. . . the flood came so heavy through Fruita that it carried trees, still full of apples, all the way to Caineville. The fruit trees were just tumbling over and over in the mud. There were fat pigs still swimming in it when they got to Caineville. [5]

Thus, in addition to the routine maintenance of the ditches, farmers were forced to contend with flood damage to diversion dams and ditches on a frequent basis. Wagon roads covered with boulders or plant debris also required clearing after floods.

Shown on the Fruita Township Map is an extensive irrigation ditch that ran along the north side of the Fremont River to Nels Johnson's lands. In 1900 Leo Holt's brother, Aaron, settled 40 acres west of Elijah Behunin's homestead. In 1902 he diverted water from Sulphur Creek to irrigate his property on which he grew wheat, oats, alfalfa, potatoes, corn, apples, peaches, apricots, and cherries. This is thought to be a representative list of farm products grown at Fruita in the early twentieth century. The area's relative isolation encouraged residents to be self-sufficient by cultivating basic food crops.

| |

| From left to right, Clara, Cora, and Carrie Oyler, 1912 | |

| |

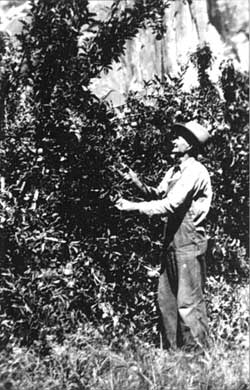

| 'Tine Oyler in his orchard, about 1920. | |

The realities of life in remote Fruita during the early part of the twentieth century could be harsh. The closest doctor and midwife lived in Loa, 27 miles away. Mothers often died in child birth (or shortly after), with relatives or neighbors informally adopting the motherless infants. When Alma Chesnut's wife died after giving birth, brother William and his wife, Dicey, took in and raised Alma's motherless older boys; the Oylers took in the newborn. 'Tine and Marie Oyler had three daughters (Carrie, Clara, and Cora), only one of whom survived beyond childhood. Clara died at age 8 of "typhoid," and Carrie at age 18 of appendicitis. [6]

By 1910 there were 9 families in Fruita, totaling 61 people (19 adults and 42 children). Only Cal Pendleton and Leo Holt remained from the earlier census, although Amasa Pierce continued to own and farm land, while having moved his residence to Torrey. In addition to absentee landlord Pierce, four of the nine families in Fruita operated fruit farms. Between 1910 and 1920 a number of properties changed hands. Michael Valentine ('Tine) Oyler bought 112 acres and Jorgen Jorgensen purchased 45 acres from Cal Pendleton.

Prior to World War I, all the farms in Fruita had orchards ranging in size from .5 to 3 acres. [7] During the war years, increasing acreage was planted in fruit, and several properties changed ownership, resulting in the concentration of large orchard acreage by a few individuals. By 1917 the following property owners had emerged as the most prominent fruit growers of this era: 'Tine Oyler, Cal Pendleton, and Don Carlos Pendleton, each owning orchards reported to be 4 to 7 acres each. Oyler's purchase of George Carrell's orchard in 1916 elevated him to being one of Fruita's most prominent fruit growers, a position he held until the sale of his land to Max Krueger in 1941. Prior to World War I, Oyler formed a brief partnership with a young teacher named Cliff Barton, who lived for a time with the Oylers. According to Cora Smith ('Tine Oyler's daughter), Barton wanted to start a business and had no difficulty interesting Oyler in his plans. Barton bought the first truck in Fruita, and then Olyer bought one, planning to haul fruit to markets in the upper plateau towns. Together they planted more fruit trees. The joint venture was short-lived, as Barton was drafted into the army during World War I and subsequently died in Germany. [8]

| |

| 'Tine Oyler's new orchard, looking west, about 1917. | |

Early homes constructed in Fruita were log cabins or small, wood frame, gable-roofed houses. They started out as one large room, and when circumstances improved, lean-tos were added to the rear (bedrooms), side (kitchen), and front (porch). According to Cora Smith, "all the houses were like that." [9] Few families in Fruita and the surrounding communities could afford the extravagance of painting their homes. Smith took great pride in relating that her father had a house built of finished lumber that was painted "white with green trim." [10]

In 1914-1915 the town received tri-weekly mail. Private residents served as postmasters and their homes as "post offices" until about 1918, when the post office was abolished. [11] Oral tradition has it that, at the large cottonwood tree located at the bend of the present-day Scenic Drive, the postal carrier from Torrey transferred the mail to another carrier who then carried it to upriver settlements. [12] At some point in time, mail boxes were attached to this tree (most likely after the post office was discontinued). Referred to as the "mail tree," it is now about 120 years old.

| |

| Early view of Fruita, looking south. (undated) | |

A number of other trees were planted by early settlers and are noteworthy features of the landscape. There is a prominent stand of mature walnut trees located on land which was once part of the Nels Johnson homestead. They are situated in a row along the Scenic Drive, bordering the Johnson Orchard, and may date to the early period of settlement. [13] Just south of 'Tine Oyler's vineyard are located a row each of mature pecan and walnut trees, reportedly planted by Oyler [14] A single mature walnut tree also grows in front of the Gifford house. Another mature walnut tree stands prominently on the edge of the Mulford Orchard. The Mulford family refers to it as the "Brigham Young walnut tree." [15] Also worthy of note are the isolated Lombardy poplars scattered throughout the district. It is likely that some are remnants of poplar rows that once marked boundary lines or created windbreaks in early Fruita. [16]

During this period and throughout its later years, Fruita was not only significant as home to the handful of families who lived in the valley, it was a welcome oasis to those travelling through the arid region. The valley offered green fields, orchards, and shade against the dramatic backdrop of the canyon. Fruita attracted those who lived in the plateau towns to the west and the canyonlands to the east, and was (and still is) a traditional gathering place for holidays, family reunions, and fruit harvests.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

http://www.nps.gov/care/clr/clr3a.htm

Last Updated: 01-Apr-2003