|

Capitol Reef

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 11:

FROM MONUMENT TO

PARK, 1969 TO 1971

Before addressing the reaction to Capitol Reef's expansion, let us first examine the new boundaries and resources enclosed in the enormously enlarged monument. A total of 215,056 acres were added to the existing monument. This land was added to the national park system because, in the words of the proclamation,

it would be in the public interest to add to the Capitol Reef National Monument certain adjoining lands which encompass the outstanding geological feature known as the Waterpocket Fold and other complementing geological features, which constitute objects of scientific interest, such as Cathedral Valley. [1]

The key scientific qualification (required by Section 2 of 1906 Antiquities Act, which authorizes these presidential proclamations) of the Capitol Reef expansion was the same as that singled out in the initial enabling proclamation back in 1937: the unique geology of the Waterpocket Fold.

Proclamation #3888

According to the December 1968 press release that accompanied the inauguration day proclamations, "only a fraction of the dramatic structure and the geologic story" were protected within the old monument boundaries. The press release declared:

Now, with the addition of 215,056 acres, the entire Waterpocket Fold running north to south and striking downward west to east, is brought within the National Park System in order to present a complete geologic story and to preserve in its entirety this classic monocline. Seventy miles of it are now in the national monument in Wayne, Emery, and Garfield Counties [a little portion in Sevier County was also included]....Included in the north end of the enlarged Capitol Reef National Monument is Cathedral Valley. As its name implies, the valley contains spectacular monoliths, 400 to 700 feet high, of reddish brown Entrada sandstone, capped with the grayish yellow of Curtis sandstone. These colorful "cathedrals," many of them freestanding on the valley floor, provide unusually striking land forms." [2]

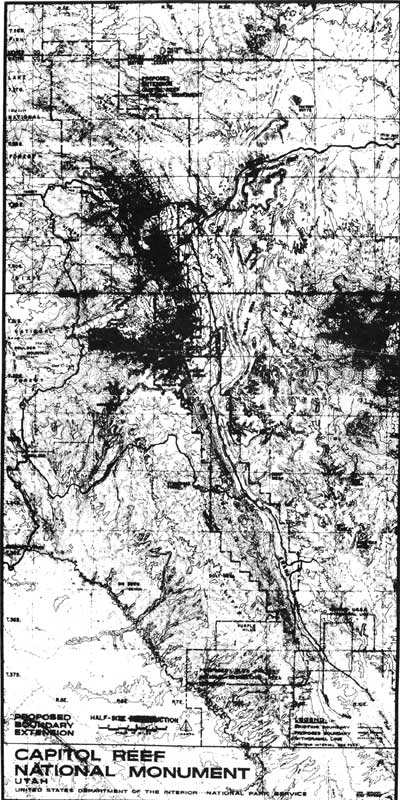

The new boundary lines were drawn along section lines and gave the monument the look of a long, jagged comma across the western Colorado Plateau, just like the geologic fold it now protected (Fig. 29). There was not a lot of land added to either side of the actual fold, but it included:

1) the Hartnet Mesa and South and Middle Deserts that make up Cathedral Valley north of the actual fold (an area Charles Kelly had argued worthy of National Park Service protection back in the 1950s);

2) a little land on the west and east of the former monument boundaries as requested by Superintendent Heyder to insure that the Scenic Drive was well within the monument and that the scenic views seen by most visitors were not compromised by any future encroachments; and

3) several dozen sections to the south were included at the eastern base of the Fold and also extended slightly onto the scenic Circle Cliffs plateaus to the west.

|

| Figure 29. Expanded boundary of Capitol Reef National Monument, January 1969. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

The eastern boundary was likely set to include the beautiful Strike Valley as well as the north-south running Notom-Bullfrog Road. It also spread onto Big Thompson Mesa, which is directly east of and above Halls Creek. It is interesting to note that the southern boundary was just below the Fountain Tanks - natural waterpockets used by travelers and stockmen for 100 years. The spectacular Halls Creek Narrows were not included in the 1969 proclamation nor in the proposed Glen Canyon National Recreation boundary, which was southwest and southeast of the new monument boundaries. [3]

The most significant problems with this ambitious expansion concerned land use. The new monument boundaries now embraced an additional 25,280 acres of state land and 1,080 acres of private land, as well as an estimated 11,000 mining claims, 26,000 acres of oil and gas leases, and 62 grazing permits allowing as many as 6,000 AUMs (Animal Units per Month, or as much as a cow and her calf or five sheep can eat in one month). [4] The proclamation specified that all valid, existing rights, such as mining claims, would be protected. In addition, the proclamation reiterated Capitol Reef's previous proclamations of 1937 and 1958:

Nothing herein shall prevent the movement of livestock across the lands included in this monument under such regulations as may be prescribed by the Secretary of the Interior and upon driveways to be specifically designated by said Secretary. [5]

The new monument boundaries now protected a great deal of geologic and scenic splendor and an abundance of high desert resources. The problem was that, by expanding the monument at the relatively late date of 1969, any remotely promising mining or grazing land was already claimed. Thus, the National Park Service would be forced to allow mining and grazing in the new monument lands until either the claim or permit could be proven invalid, phased out, or purchased.

Managing these additional resource uses has proven to be at least as difficult as protecting the unspoiled, natural resources of older national parks and monuments. Yet, even before the staff at Capitol Reef could venture into managing its new lands, attacks from neighbors, multiple-use advocates, and the Utah congressional delegation put the National Park Service on the defensive just to save the newly expanded monument.

Initial Reaction To Capitol Reef Expansion:

Jan.-Feb. 1969

That third week in January 1969 saw a flurry of questions and responses that plunged Capitol Reef management into chaos. As mentioned earlier, Superintendent Heyder was unsure of the exact placement of the new boundaries. Thus, when the news leaked, Heyder could do no more than stall for time. The problem was exacerbated by the fact that copies of the specific proclamation and boundary map were not sent directly to the regional office or to the park. Heyder had to wait several days after the inauguration (January 24) to get a copy of the Federal Register with the exact expansion boundaries. [6]

Heyder recorded a number of information requests from ranchers, miners, reporters, forest service, and Utah highway officials, who all wanted information on the new boundaries. [7] The superintendent could only promise to let them know the specifics as soon as he, himself, knew them. In a January 23 editorial, the local Richfield Reaper reported, "Capitol Reef personnel were aware of some type of expansion plans, but indicated that what had been talked of and what the proclamation would include will be two different things." [8]

The failure to inform Superintendent Heyder immediately of the expanded boundaries enabled the opposition to spin out of control with unsubstantiated rumors. It also didn't help that Heyder and his staff had no idea what grazing and mining claims existed in the new addition.

According to Heyder, George Hatch, president of the KUTV television station in Salt Lake City and supporter of the expansion, borrowed a detailed grazing allotment map from the BLM, ostensibly for his own research. Hatch loaned the map to Heyder for two days before it had to be returned. All this happened after the proclamation had been issued. The lack of information from the Washington and regional offices was very frustrating for the superintendent. The Richfield Reaper quoted Heyder as saying:

It's embarrassing to us at Capitol Reef to be asked about the proposal when we can't give any answers. Rumors are flying at a brisk pace, including one which states that the west boundary will go to Bicknell [22 miles away]. [9]

The most celebrated initial act of opposition came from the town of Boulder, where resident ranchers and speculative miners had claims to the southern half of the Waterpocket Fold. The day after the inauguration, before any specific boundary information had been released, the five-member Boulder Town Board passed a resolution changing the name of the town to "Johnson's Folly." According to Board President Cecil Griener, the Capitol Reef addition would eliminate winter grazing for cattle raised by Boulder ranchers, thereby creating a ghost town surrounded by ghost ranches. [10] Apparently, Griener and the Boulder Town Board were under the impression that the entire Circle Cliffs area east of Boulder was to be included. This inaccurate rumor continued to spread and could not be quashed by National Park Service officials because they themselves did not know the exact boundaries. Until they did, there was plenty of grist for the opposition rumor mill.

Other immediate local resistance was voiced in regional newspapers such as the Richfield Reaper, and in a Utah House of Representatives resolution introduced by Royal Harward of Wayne County. These objections were not surprising, given Southern Utah's customary land use habits. The objections coming from Utah's congressional delegation, however, were of greater concern.

In the weeks preceding the proclamation, both Utah senators were active in Utah tourism and land use issues. Sen. Moss introduced two bills to aid tourism and the southern Utah parks. This legislation would create a Canyon Country National Parkway from the Glen Canyon Dam to Grand Junction, Colorado, and sponsor a large-scale development survey for the Colorado Plateau parks and monuments. [11] Meanwhile, Sen. Bennett was resisting efforts by the interior department to raise grazing fees, as well as other plans that he believed would "have a serious negative economic impact on ranchers and their communities in Utah." [12]

Then, on Friday, January 17, Udall met with the entire Utah congressional delegation, informed members of the impending proclamations affecting Arches and Capitol Reef National Monuments, and then "swor[e] them to secrecy." According to Moss,

Secretary Udall said his department's examination showed no working mining claims in the two areas and very little grazing. He said there might be some 'tailoring' of the boundaries but that this will be up to Congress to decide. [13]

As mentioned in the previous chapter, Udall was optimistic that he had persuaded the Utah delegation that the monument expansions would be good for their state. Once the news leaked late that same day, however, Moss issued a statement calling for field hearings similar to the ones he'd conducted for his Canyonlands National Park legislation several years earlier. Also on January 17 (whether before or after the Udall meeting is unknown), Bennett reintroduced his bills to create Arches, Cedar Breaks, and Capitol Reef National Parks within their old monument boundaries. Bennett also warned, "I will insist on field hearings on my bills and I want to make certain that mining rights and the likes are fully protected." [14]

Two days after the proclamation, Moss introduced Senate Bills 531 and 532, which would "designate these enlarged areas as national parks." The purpose of this action, according to Moss, was to insure that Congress had a major role in deciding the areas' future that local opinion was considered, and that, in the long run, tourism would increase. As a Democrat who had previously guided the Canyonlands National Park legislation through Congress, Moss seemed generally supportive of the proclamations. [15]

The Utah congressional delegation's reaction to the proclamations split along party lines, lone Democrat Moss supporting expansion and the Republicans opposing any expansion at that time. Yet, they all supported changing Capitol Reef's status from a monument to a national park, primarily because national parks attracted more tourism.

By January 31, the overwhelmingly negative reaction from within Utah fueled Bennett's offensive against the "land grab." On that date, Bennett introduced into the Congressional Record several newspaper articles and editorials in opposition to the Arches and Capitol Reef expansions. [16] Moss, on the other hand, introduced a newspaper article from The Ogden Standard-Examiner that supported the monument expansions and urged national park designation for the areas. [17] Yet Moss was the lone vocal supporter in those first few weeks.

On February 5, Bennett sent a letter to 16 leaders or advocates for multiple-use, including the state directors of lands, natural and water resources, and the heads of the state mining and livestock lobbies. Bennett spelled out his plan to eliminate the expanded boundaries and make the former national monument lands into national parks. He added, however, that "maybe there is other land, less in volume than the amount taken, which perhaps should be added." He desired information, "guidance and a frank expression of the problems... that this action ha[d] created." He sought details on potential grazing and mining possibilities in the lands included in the Arches and Capitol Reef proclamations, as well as sites for future roads and facilities. This letter was an effort on Bennett's part to get additional facts on the growing controversy. Since the letter was sent only to multiple-use advocates, though, one could conclude that the senator's mind was already focused toward continued opposition. [18]

The first official step in opposition was taken when Sen. Bennett and fellow Republican Rep. Lawrence Burton introduced bills on February 7 to limit the size of any future national monument to 2,560 acres. According to Bennett, this would "preclude future unilateral executive action involving thousands of acres of land." [19] This was followed by some inflammatory testimony at the Republican-sponsored Lincoln Day meetings conducted by Bennett and Burton in Moab and Escalante one week later.

Burton and Bennett's opinions were, by now, well known. Both were adamantly opposed to what they now consistently called "that illegal land-grab," but they showed a willingness to negotiate on some land increases and/or national park status. The first stop on their southern Utah tour was Monday, February 10 in Moab, where some 200 people gathered to express their opinions on the proclamations. According to newspaper reports, the only voice in favor of the proclamations was that of Superintendent Bates Wilson of Arches and Canyonlands. He informed the senators that the expansion was needed to give the monuments enough protection to justify national park status. [20]

The overwhelming concern at the Moab meeting was the anticipated effect of the additions on the local economy. While it was reported that most in attendance favored a guaranteed phase-out of grazing and mining interests within the new boundaries, the director of the Utah Geological Survey argued that Capitol Reef National Monument should be reduced back to its previous size to free oil and tar sands deposits that were "one of Utah's greatest economic potentials." [21]

After a day touring Arches, Burton and Bennett flew over Capitol Reef before landing in Escalante for a Lincoln Day dinner and town meeting. Heyder and Chief Ranger Bert Speed drove over to Escalante and, at first, could not find the dinner site since both the gas station attendant and grocery store butcher refused to talk with National Park Service officials. Once at the dinner, Heyder was asked by Bennett and Burton to sit at the head table and provide answers at the next day's town meeting. [22]

According to Heyder, the predominant concern of those at the Escalante town meeting was the expected impact on grazing. When Heyder attempted to reassure ranchers that existing stock driveways would not be affected and that grazing privileges within the addition would be addressed in time, Burton said sarcastically, "Well, folks, that's the Department of Interior answer for you." Heyder was upset by this obvious put-down, but after the meeting Burton assured him that it was only politics and that Heyder had answered all the questions quite well. [23] There are no transcripts of these informal meetings, and the Ogden Standard-Examiner was the only Utah paper to report on the Escalante segment of the trip. After the dinner on February 11, Bennett stated:

What I heard tonight is similar to what I heard in Moab last night. These people are not so much concerned with the withdrawal as with the way it was handled. No hearings were held. No people were contacted. It was merely a last minute land-grab by the Johnson administration. [24]

With their congressmen backing it up, the local resistance rhetoric only increased. To demonstrate the negative impact Capitol Reef's expansion would have on the neighboring economies, 41 families claiming at least partial grazing rights within the new boundaries gathered at the Wayne County seat of Loa to publicize their plight. Don Pace, rancher and Wayne County commissioner, testified:

Most of us have been in the ranching business here all our lives. Our fathers and grandfathers pioneered this part of the state, long before there were any national monuments or parks. We have worked all our lives to improve the cattle industry here and have built our homes and lives on this business. Now with a stroke of the pen, all this is headed for doom. [25]

According to Pace, the families were willing to accept the new monument boundaries so long as traditional winter grazing was allowed to continue. In late February, however, the National Park Service had yet to decide what to do about the grazing privileges. Left hanging, Pace and the others pressed their case and voiced their pessimism:

We just don't know what we will do or where we can go....It's a real problem because most of us are full-time ranchers and don't have any other business to fall back on. We are just hoping that Congress will realize that we are people and not statistics, and that just because there are only 200 of us, we shouldn't have to be written off for some political whim. [26]

The outcries against expansion were inevitable in such an isolated, conservative region historically dependent on multiple-use land. No matter when or how the proclamation was announced, the monument's enlargement would have been seen as another high-handed act by a federal government oblivious to struggling local economies. Nevertheless, the political struggles that delayed the proclamations until the final hours of the Johnson administration, and the uncertainty and secrecy that left the field personnel so unprepared, fueled panicked rumors among Capitol Reef's neighbors and rhetorical attacks from Washington politicians.

Of course, not all opinion opposed the proclamations. Shortly after the Bennett and Burton town meetings, Sen. Moss met with Utah conservation leaders and tourism promoters to discuss the enlargement issue. Moss told the group that he had asked the Bureau of Land Management and the National Park Service to investigate the multiple-use potential of the areas in question. He also appraised them of the Bennett and Burton legislation proposals and of his own plans to hold Utah hearings in the near future. The group agreed that the people of the area simply didn't realize the long-term benefits the enlargements and national park status would have for tourism business. Some also pointed out that the increased grazing fees from the previous year "helped stir the emotions of the opponents of the enlargements." The group felt that the hearings should be delayed for at least another month to let resistance subside. [27]

Once the immediate furor over the proclamation died down, it was up to Bennett, Burton, and Moss to orchestrate legislation that would finalize Capitol Reef's boundaries and status. That it took an additional two years to pass the Capitol Reef National Park bill signifies the continued controversy over the initial proclamation, the strength of the multiple-use argument, and the complex resource issues involved.

The Proposals Of Bennett, Burton, And

Moss

Bennett, Burton, and Moss each had his own plan for Capitol Reef National Monument. On March 17, Sen. Bennett introduced amendments to his bills to make Capitol Reef and Arches national parks. The amendments clarified the boundaries as being those as of January 1, 1969--prior to the expansion proclamations. [28] Fellow Republican Burton also favored reducing the monument's size, but would be willing to include some of the newly added lands with no grazing or mineral potential. [29]

If these Republican-sponsored bills became law, they would supersede President Johnson's proclamations. The problem Bennett and Burton faced was that theirs was the minority party. Because there was little chance of their bills passing without significant amendment, the legislation introduced by the Utah Republicans was clearly intended to represent local opposition to the "land-grab."

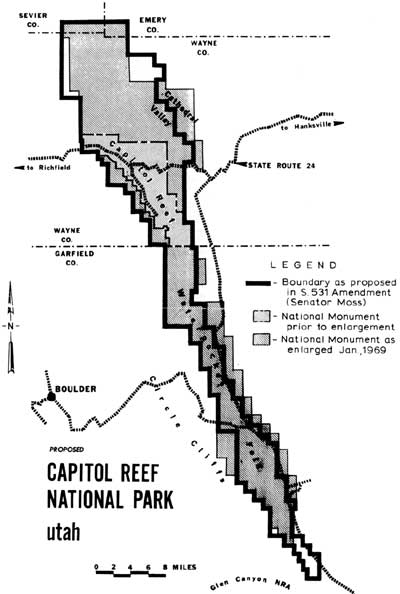

Meanwhile, Moss' plan was to eliminate 56,000 acres in favor of 29,000 acres not included in the January 20 proclamation, for a net decrease of 17,280 acres. After an inspection tour of Capitol Reef and consultations with National Park Service, Bureau of Land Management, and University of Utah geologists, Moss established "what areas should be included and what might reasonably be excluded because of their unsuitability for national park status and the need to use them for other multiple-use purposes." [30]

Moss' bill, S.531, as amended, would trim lands from either side of the southern half of the fold and in the eastern Hartnet and Blue Valley areas northeast of Fruita. The goal, according to the senator, was to "remove much of the land under grazing permit." Moss also introduced amendments that would allow grazing permits to continue under the present holders and their heirs. [31] In return, Moss proposed to add land in the lower and upper Cathedral valley and extend the monument boundary to include the Halls Creek Narrows (Fig. 30). To gather support for his bill, Moss scheduled hearings in Salt Lake City on May 15, in Richfield on May 16, and in Moab the following day.

|

| Figure 30. National park boundary as proposed by Sen. Frank Moss, 1969. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

http://www.nps.gov/care/adhi/adhi11.htm

Last Updated: 10-Dec-2002