![]()

MENU

![]() Eruption and White Bird Canyon

Eruption and White Bird Canyon

Looking Glass's Camp and Cottonwood

Kamiah, Weippe, and Fort Fizzle

Cow Island and Cow Creek Canyon

Bear's Paw: Attack and Defense

Bear's Paw: Siege and Surrender

|

Nez Perce Summer, 1877

Chapter 2: Eruption and White Bird Canyon |

|

Chapter 2:

Eruption and White Bird Canyon

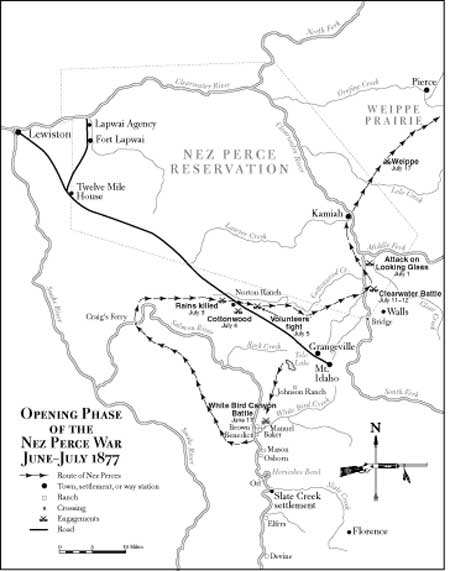

Following the council at Fort Lapwai with General Howard, the Nez Perces started for their home areas to gather in their livestock and prepare for the move onto the reservation. Joseph and Ollokot crossed the Snake River at Lewiston and ascended the Grande Ronde River to their camp near the mouth of Joseph Creek in the Wallowa Valley. White Bird and Toohoolhoolzote led their bands south to the Salmon River. Looking Glass headed east to his home on the Middle Clearwater above the subagency of Kamiah and within the reservation boundary. In returning home, the people traced the geography that became the setting for the opening stage of the war. Oddly enough, the Wallowa region that so prominently comprised the crucible of dispute lay beyond the zone through which they traveled. In its configuration, the area formed a rough, left-leaning trapezoid with sides about forty miles long that encompassed some sixteen thousand square miles in west-central Idaho between the Snake River and the Clearwater Mountains, and that ran from slightly north of the Middle Clearwater River south to include the mountainous terrain between the Snake and Salmon rivers. Its northern part comprised the Nez Perce Reservation, as reshaped according to the 1863 treaty, while to the south lay the broad and undulating Camas Prairie, favorite rendezvous point for all the Nez Perce bands.

Several white communities dotted the scene. From Lewiston, in the extreme upper left corner of the trapezoid, the line of settlement followed east along the Middle Clearwater to the Lapwai Agency and Fort Lapwai, ten miles away, and diagonally southeast some sixty-six miles to the town of Mount Idaho, with approximately a hundred inhabitants, and the adjacent hamlet of Grangeville. The road running between Lewiston and Mount Idaho passed through the low-lying Craig's Mountain range before splitting the Camas Prairie. At a point forty-eight miles from Lewiston and nineteen from Mount Idaho, and near Cottonwood Creek, stood an inn, or halfway house, known as Norton's Ranch or Cottonwood Ranch, where travelers sought rest and sustenance. Several miles south of Mount Idaho, the terrain began a sharp seven-mile descent to the Salmon and its tributary, White Bird Creek, named after the Nez Perce leader whose band inhabited the area. Below White Bird Creek, and along several eastern affluents of the Salmon, stood many scattered homesteads of white farmers and stock raisers. Militarily, the entire area lay within the District of the Clearwater, a part of Howard's administrative domain within the Military Division of the Pacific. [1]

General Howard arrived back at Fort Lapwai on June 14 to be on hand when the nontreaty Nez Perces moved onto the reservation. "The officers, the government employees at the agency, and the friendly Indians," he reported, "all expressed the belief that the 'non-treaties' intended to comply with the promises made to the agent and myself the month previous." [2] Earlier, troops of the First Cavalry from Fort Walla Walla had arrived to support those at Fort Lapwai in anticipation of the Indians' arrival. Visiting the Lapwai Agency on June 4, Sergeant Michael McCarthy of Company H found it lifeless and littered with trash. "The only semblance of animation about the whole agency [was] a few Indian boys catching minnows in a sluggish millrace." Eight days later, it was generally felt that the nontreaties were coming and that the soldiers would have no trouble with them. "A few days and we will return to Walla Walla," penned McCarthy. "Quiet peace reigns. Joseph has put his pride in his pocket and is now I hear crossing his stock and coming in." Unconcernedly, the sergeant recorded that White Bird, "a grand looking Indian whose headdress is decorated with an eagle's wing, is present at our morning drills nearly every day for a week. He is attended by an orderly who rides the regulation distance behind him. We must be of interest to him, so punctual is his attendance." As late as June 14, McCarthy commented on the tedium at Fort Lapwai, noting that there "is not a thing to break the monotony except mosquitos." [3]

On that day, Howard received a letter from a Mount Idaho resident stating that the citizens of that community were becoming increasingly suspicious of the tribesmen gathered nearby. [4] The general instructed Captain David L. Perry, commanding the two companies of First Cavalry at Fort Lapwai, to prepare a detachment to go the next day and ascertain the intentions of the Nez Perces known to be camping just off the edge of the reservation. Since returning to their home areas from the Fort Lapwai council, Joseph, Ollokot, White Bird, and the other band leaders had readied their people for moving onto the reserve. Under the watch of Captain Whipple and his cavalrymen, the Wallowas had spent much of the interval packing their possessions and corralling hundreds of free-grazing horses and cattle and fording all, as well as themselves, across the raging and freezing waters of the Snake, now swollen from the spring runoff. Many animals escaped the roundup and were later confiscated by white settlers, while others were swept away and drowned. On May 31, most of the tribesmen crossed at a point called Dug Bar, near the mouth of the Imnaha and opposite the mouth of the Salmon, then traveled east for ten miles before fording the Salmon and moving north through a defile known as Rocky Canyon. They left their cattle below the Salmon, intending to return for them before the deadline.

Around June 3, the people began converging at the sacred grounds of Tepahlewam (Split Rocks, or Deep Cuts) on Camas Prairie near a large pond at the time referred to as "the lake," but today called Tolo Lake, about six miles west of Grangeville. Those assembling included the five recognized nontreaty bands, as follows: The Wallowas, with Joseph, Ollokot, and other leaders, included 55 men; the Lamtamas, or so-called White Bird band, under their principal chief, White Bird, included 50 men; the Alpowais of Looking Glass included 40 men (all were not present at the assembly); the Pikunans of Toohoolhoolzote, who had travelled over from the Wallowa with Joseph and Ollokot, included 30 men; and Husis Kute and the Palouses included 16 men, for a total of 191. Only half of these, say 95, were warriors, the rest being either too young or old for that designation. There were also approximately 400 women and children in all the bands, so that the total nontreaty Nez Perce population at Tolo Lake stood at slightly less than 600. [5]

Tolo Lake, formed at least ten thousand years ago and the sole natural lake on Camas Prairie, had historically afforded a popular early summer rendezvous where the Nee-Me-Poo could observe their Dreamer ceremonies, greet friends and relatives in other bands, race their ponies, exchange gifts, and gather the popular camas bulbs. At Tolo Lake, too, the Nez Perce leaders of the different bands represented their people in the council, and the decisions of the council regarding peace and war became binding on all. Generally, war leadership evolved based on a warrior's record and commensurate ranking status and his ability to attract and maintain a followership. Joseph, a civil leader and descendant of a popular chief, was not regarded as such among the people, and he was, moreover, apparently without extensive military experience. Nonetheless, as co-leader of the large Wallowa band, Joseph stood as an influential force in multi-band councils. Conversely, the other Wallowa co-leader, Ollokot, was highly regarded in military matters, and he provided skilled counsel during the subsequent struggle. Other noted war leaders included White Bird, chief of the Lamtamas, who in his mid-fifties was well past warrior age but possessed considerable knowledge accrued during his many years and was viewed as a senior adviser; Chuslum Moxmox (Yellow Bull), a war leader, also of the Lamtamas; Looking Glass, the Alpowai, fortyish and well respected for his war prowess, and who emerged as perhaps the dominant military leader as the conflict wore on; Toohoolhoolzote, chief of the Pikunans; Koolkool Snehee (Red Owl), an Alpowai headman of Looking Glass's band; Wahchumyus (Rainbow) and Pahkatos Owyeen (Five Wounds), who were not present at Lake Tolo but who shortly joined White Bird's people. [6]

The Lake Tolo councils in 1877 witnessed prolonged and rancorous debate among the leaders of the different bands regarding their imminent movement onto the reservation. Despite the agreements made at Fort Lapwai in May, many tribesmen bridled at giving up their freedom and their lands, and the growing furor over the issue produced much dissension, building resentment and second-guessing over the earlier decision. Against the backdrop of this tense and emotional convocation occurred an incident that further obscured past consensus, intensified the fractiousness and sense of rage among the people, and in the end provoked irrevocable armed conflict. On June 13, shortly before the deadline for removing onto the reservation, White Bird's band held a tel-lik-leen ceremony at the Tolo Lake camp in which the warriors paraded on horseback in a circular movement around the village while individually boasting of their battle prowess and war deeds. According to Nez Perce accounts, an aged warrior named Hahkauts Ilpilp (Red Grizzly Bear) challenged the presence in the ceremony of several young participants whose relatives' deaths at the hands of whites had gone unavenged. One named Wahlitits (Shore Crossing) was the son of Eagle Robe, who had been shot to death by Lawrence Ott three years earlier. Thus humiliated and apparently fortified with liquor, Shore Crossing and two of his cousins, Sarpsisilpilp (Red Moccasin Top) and Wetyemtmas Wahyakt (Swan Necklace), set out for the Salmon River settlements on a mission of revenge. [7] On the following evening, Swan Necklace returned to the lake to announce that the trio had killed four white men and wounded another who had previously treated the Indians badly; Lawrence Ott, however, had not been found. Inspired by the war furor, approximately sixteen more young men rode off to join Shore Crossing in raiding the settlements.

The news of the killings electrified the assemblage, and now anticipating inevitable confrontation with Howard's soldiers, the bands started moving away from the lake. The so-called treaty people present in the camp, afraid of being implicated in the murders, hurried back to the reservation while the nontreaties traveled to Cottonwood Creek. Seeking to avoid trouble with the soldiers, Looking Glass led his people back to their tract near the mouth of Clear Creek on the Middle Clearwater, while Husis Kute camped with his Palouses a short distance away on the South Fork of the Clearwater. Joseph and Ollokot had been away from the Nez Perce assembly at Tolo Lake when these incidents happened. They had gone below Salmon River to butcher some cattle and were sent for immediately after the assembly received news of the murders. Hoping to avert war, the two rejoined their band along the Cottonwood, but by then the tragic course of events precluded further discussion of restraint among the bands. When the two leaders sought to bring their camp near that of Looking Glass for security, that chief—incensed at White Bird over the killings—resisted the approach. They instead withdrew to the Lamtamas camping ground at the mouth of White Bird Creek on the Salmon. The killings—and the schisms they were creating among the Nez Perces themselves—dashed any hope that Joseph and Ollokot might still have retained for a peaceful movement onto the Lapwai reservation. [8]

Continued >>>

Top

Top|

History | Links to the Past | National Park Service | Search | Contact |

Last Modified: Thurs, May 17 2001 10:08 pm PDT

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/greene1/chap2.htm

![]()