![]()

MENU

Eruption and White Bird Canyon

Looking Glass's Camp and Cottonwood

Kamiah, Weippe, and Fort Fizzle

Cow Island and Cow Creek Canyon

Bear's Paw: Attack and Defense

![]() Bear's Paw: Siege and Surrender

Bear's Paw: Siege and Surrender

|

Nez Perce Summer, 1877

Chapter 13: Bear's Paw: Siege and Surrender |

|

Chapter 13:

Bear's Paw: Siege and Surrender (continued)

Despite the arrival of the tents and supplies, the night of October 1 seems to have been even more miserable for the soldiers than the previous night. One man was killed and another wounded during the day's action. [50] These two represented the last army casualties at Bear's Paw. Seventh Cavalry Sergeant Stanislaus Roy, who arrived with the train, recalled the scene that evening: "The Troops were all on the skirmish line and the fight was still on. . . . Coffee was made for the troops and carried on [the] skirmish line to the men, and I took charge of the Troop on the line that night." [51] "The wagon train . . . brought little fuel and it snowed that night and some of the wounded had their feet frozen." [52] Lieutenant McClernand recalled that "that night I suffered more than I ever did in my life."

At nine o'clock it commenced raining, and this at midnight turned into snow. The men in our squadron did not have their blankets, I had not even an overcoat. Under the circumstances we did not find the bare ground especially warm, . . . and the next morning, being unable to mount my horse, I was taken to the hospital tent. Here a fire was made from pieces of wagons which had been broken up after the arrival of the train. [53]

And Tilton observed that "the men's blankets are wet and they are cold and uncomfortable." [54]

During the night, the infantry and cavalry units again shifted positions, with Snyder's battalion of the Fifth occupying a tract "in front of the village," and Tyler's Second battalion, now short one officer in Lieutenant Jerome's absence, moving inadvertently closer to the north side of the Nez Perce camp. [55] "We could distinctly hear their voices in ordinary conversation," said McClernand, who described the activity on the line that night:

The command was dismounted, the horses led a little to the rear, and the men, after being deployed as skirmishers, were directed to lie down. Occasionally some Indians would try to escape, when the skirmishers in their front would open fire, directing their fire by the noise made, as it was too dark to see. A few of the Nez Perces succeeded in dashing through between our skirmishers, followed by a perfect volley of wildly directed shots. However, several dead Indians were found in our front next morning. One horse in my troop was killed, and my own horse stampeded and fell into the hands of the Indians. As there were only two officers present, we were obliged to pass frequently from one end of the line to the other. Each man was required to call softly to his neighbor at intervals of about five minutes. It was in this way one man was found to be dead, having been shot through the body—probably by the Indians who broke through our lines. Even this frequent calling to each other was not sufficient to prevent some of the men from falling asleep, they were so worn out with fatigue and benumbed by cold. [56]

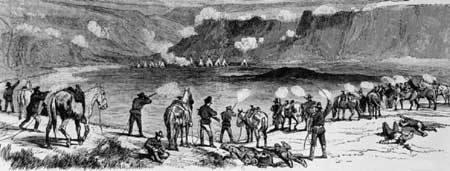

An artistic, and not altogether accurate, view of the Bear's Paw battlefield, as represented to the American public in Harper's Weekly, November 17, 1877. |

Along the encircling line of rifle pits, army cooks made their rounds only after darkness fell. The unsteady truce continued through the night and all day Tuesday, October 2, with but occasional shots being fired on both sides. Early that day, a crew of six soldiers and six civilian packers started with sixteen pack mules for the foothills to get firewood, returning in the afternoon with mules and horses fully loaded. [57] On the lines, the prolonged lulls provoked interesting colloquies between the soldiers and the warriors, and it was reported that at one point during the fighting, when Miles was heard to yell, "Charge them to hell!" an informed Nez Perce called back in English: "Charge, hell, you God d—n sons of b——s! You ain't fighting Sioux!" [58] Meantime, Sergeant McHugh worked to prepare his ordnance for service, with earthworks being raised to protect the gun crews. "We will see what tomorrow will bring forth," wrote Private Zimmer. [59] On the evening of October 2, the Second Cavalry troops moved "from the extreme right flank to the [extreme?] left, covering a field gun poised so as to command the place where the Indians came down in the evening to get water." [60] Similarly, Zimmer noted that "our battalion was supporting the big guns [sic] on the north [sic—west] side of their camp." [61] This position of the twelve-pounder lay approximately fifteen hundred yards directly west of the noncombatant-occupied ravine and afforded the gun a clear and direct access with its projectiles into the entire east-west alignment of that ravine. Supporting rifle pits to be manned by Second cavalrymen were raised while the cannon was emplaced. [62] In the camp, the people used the prolonged reprieve to improve their defenses. For warmth, they burned some tipi poles dragged over from the village. [63] Joseph broached the issue of surrendering, but the people remained divided. He later remarked: "We could have escaped from Bear Paw Mountain if we had left our wounded, old women, and children behind. We were unwilling to do this. We had never heard of a wounded Indian recovering while in the hands of white men." [64]

This Civil War-era model 1857 bronze twelve-pounder Napoleon cannon weighed more than twelve hundred pounds. It was mounted on a wooden carriage and used by Miles's command to send fuse-detonated explosive shells against Nez Perce noncombatants at Bear's Paw. Courtesy Paul L. Hedren. |

At daybreak Wednesday, the white flag still floated over the Nez Perces' line. Miles used the time to move his camp a bit more upstream "so as to be better protected from the rifle pits of the Indians." [65] He also sought to ready his twelve-pounder, decreeing that if the tribesmen did not come to terms by midmorning he would turn his artillery on them. [66] While the breech-loading Hotchkiss was a new addition to the command, Miles had earlier used the Napoleon gun against the Sioux and Northern Cheyennes at Wolf Mountains, Montana, the previous January, an engagement that resulted in the surrender of many of those tribesmen. Named for Emperor Louis Napoleon, under whom its use became popular in France, the gun with its wooden carriage and limber weighed thirty-two hundred pounds and was drawn by six mules. It delivered explosive shells with pronounced effect against targets as far off as seventeen hundred yards, and its principal benefit lay in its capability to vary its trajectory from flat to arcing like a howitzer. Although prized during the Civil War as an effective anti-personnel weapon over quarter-mile distances, the great weight and lack of easy maneuverability of the Napoleon made it a cumbersome field component on the plains frontier. [67]

Because of space limitations posed by the wagon transportation, only twenty-four shells had been carried with the train and were available for use at Bear's Paw. [68] Yet when the gun opened on the morning of the third, it quickly had a deadly physical and psychological impact among the tribesmen. "At 11 o.c. a.m.," wrote Tilton, "firing began on the village with both field pieces and small arms." [69] Lieutenant Romeyn said of the twelve-pounder, "its boom told the Indians that a new element had entered for their destruction." Describing the effect of the Napoleon's fire, Romeyn continued:

It was almost impossible, owing to the shape of the ground, to bring it to bear on the pits now occupied by the hostiles, who . . . took refuge in the banks of the crooked "coulees" where no direct fire could be made to reach and where the shells, if burst over them, were likewise liable to injure our men on the high ground behind. A dropping or mortar fire was, however, obtained by sinking the trail of the gun in a pit dug for it and using a high elevation with a small charge of powder. This made the fire effective. [70]

The cannon fire, however, must have occurred sparingly because of the small number of rounds on hand. As the shooting went on, the sun briefly appeared, but then it clouded over and snow fell intermittently. [71] The artillery fire had an immediate impact among the people. A packer remembered that "when that big gun went off you never heard such howling from squaws, dogs and kids." [72] Other than this, there was little response. The warriors fired only a few shots in return. "They are either short of ammunition or else we are too well entrenched for them to waste ammunition upon us," wrote Captain Snyder. He believed that the tribesmen would not surrender and "we will have to starve them out. To charge them would be madness." [73] Zimmer recorded that despite "a good shelling" of their camp, the Nez Perces "are well fixed & intend to wear us out." [74] That night Miles started a courier to Fort Benton with dispatches for Terry describing his action to date, his casualties, and the Nez Perces' situation. "Joseph gave me a solemn pledge yesterday that he would surrender," he wrote, "but did not, and they are evidently waiting for other Indians. They say that the Sioux are coming to their aid. . . . They fight with more desperation than any Indians I ever met." [75] Miles also took the opportunity to send a letter to his wife with an optimistic notation: "At present we have them closely surrounded and under fire, and they may yet give up." [76] Dr. Tilton prepared an account of casualties for delivery to department headquarters and noted that in anticipation of removing the wounded to Fort Buford he was already constructing litters and travois. [77]

The musketry and artillery fire continued the morning of the fourth, "a disagreeable, raw, chilly, cloudy day," said Tilton. [78] The twelve-pounder continued its discharge, delivering a harrowing impact among the people. Yellow Wolf told how one shell burst in a shelter pit, burying a small boy, a girl about twelve years old named Atsipeeten, and four women. The girl and her grandmother both died, while the others were rescued. [79] On the army line, an enlisted man described his unit's activities at getting wood and herding the captured stock. "Some were in the rifle pits popping at the Indians whenever one made his appearance." [80] This morning, Company F, Fifth Infantry, which had been on the line continuously since the thirtieth, was relieved by Brotherton's Company K. Miles later called on his battalion commanders to account for their men, animals, and equipment, with surplus horses and supplies to be delivered to First Lieutenant Gibson. Several attempts were made to open talks with the Nez Perces, but they were not so inclined. [81]

Continued >>>

Top

Top|

History | Links to the Past | National Park Service | Search | Contact |

Last Modified: Thurs, May 17 2001 10:08 pm PDT

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/greene1/chap13b.htm

![]()