|

BIG HOLE

Commemoration and Preservation: An Administrative History of Big Hole National Battlefield |

|

Chapter Three:

Administration under the U.S. Forest Service, (1910-1936)

From 1910 to 1936 the national monument was primarily under the care of the U.S. Forest Service. Although the War Department retained jurisdiction over the five-acre site around the soldiers' monument, War Department officials supported virtually every recommendation of the Forest Service concerning the proper protection and development of the grounds. For all practical purposes, the Forest Service managed the national monument and the adjoining 115-acre Gibbon's Battlefield Administrative Site (see Chapter Two) as one unit. Although the five-acre national monument was transferred from the War Department to the National Park Service (NPS) in 1933, the Forest Service continued to have a presence until the national monument was enlarged by presidential proclamation in 1939.

Just as the War Department had largely determined the size, shape, and character of this commemorative site from the day after the battle until its establishment as a national monument 33 years later, the Forest Service put its unique stamp on Big Hole National Battlefield over the next 30 years. In contrast to the War Department's rather narrow focus on honoring the soldier dead, the Forest Service took a more expansive approach by encouraging public use of the area for historical interest and recreation. This led to the development of a year-round ranger station and public campground facilities near the battlefield.

Ranger Station Development

As with so much else the Forest Service did, the withdrawal of the Gibbon's Battlefield Administrative Site was made with multiple uses in mind. As noted in Chapter Two, the withdrawal seemed like a prudent thing to do in light of the national park proposal introduced in Congress in 1906. More to the point, Forest Service officials were motivated to make administrative site withdrawals by the Forest Homestead Act of June 11, 1906, which gave citizens the opportunity to enter upon national forest land and claim up to 160 acres provided that the land was suitable for agriculture. From the young agency's standpoint, the Forest Homestead Act produced something of a land rush on the national forests. Quite apart from the threat to the Big Hole battlefield, the many homestead claims competed with the Forest Service's ability to secure good agricultural and pasture land for its own ranger stations; officials recognized the need to make administrative site withdrawals in order to preserve the agency's ability to develop these sites in the future. Thus, in the Beaverhead National Forest and throughout the West, rangers were busy recommending and surveying hundreds of administrative sites – many of which would never be developed. [1]

The Gibbons Battlefield Administrative Site contained all the essentials for a ranger station: enough agricultural land to raise a little hay for stock and to grow a vegetable garden for the ranger and his family, and suitable pasture for a few head of horses. Forest service regulations in the Use Book defined these requirements in detail and noted that care had to be taken to select sites that did not conflict with existing mineral or homestead claims. [2]

Administrative sites functioned as staging areas for the re-supply of backcountry rangers, seasonal forest guards, and fire lookouts. Forest rangers selected administrative sites along common routes of travel – generally no more than one day's horse ride from one another. Prior to the 1920s there were few roads in the national forests and travel by horse was the ranger's primary mode of travel. Consequently, the need for stock pasture was a crucial consideration. Other considerations for a site's selection included proximity to areas with exceptional fire hazard, commercial timber, or other resources (such as the historic battlefield). Finally, administrative sites were selected to be visible and convenient to the public.

It was important to the Forest Service that the Gibbons Battlefield Administrative Site was convenient to the Big Hole ranching community. In the Forest Service's early years, the rangers' most important contacts with the public were not with lumberman as one might expect; rather, they were with stockgrowers, homesteaders, and miners, all of whom required reassurance that the Forest Service was not "locking up" resources. Many forest rangers in Montana assisted with the formation of livestock associations for purposes of regulating livestock grazing on the national forests. [3]

|

| Battlefield Ranger Station in 1920. Tom Sherrill is standing by the fence. Courtesy National Park Service, Big Hole NB. |

The Forest Service had all these purposes in view when it developed the Gibbon's Battlefield Administrative Site. Built in 1912, the ranger station consisted of a four-room frame house, horse stable, and tool house. [4] The buildings were located about 400 feet up a draw from the soldiers' monument, less than 150 feet west of the five-acre national monument boundary. In contrast to the modern-day visitor center, the development site was practically on top of ground traversed by the combatants in 1877. Other improvements were added over the years. Assorted maps and inventories from the 1920s and 1930s are unclear as to when various structures were built; however, they show a growing number of buildings associated with the ranger station complex. These included a garage, woodshed, two machine storage sheds, latrine, corrals, pasture fences, water pipe line, and yard fence. [5]

The first occupants were Ranger Arthur M. Keas and his wife Frances. [6] The Keas lived at the station until July 1917. Ranger Marshall G. Ramsey moved into the station in August 1917 and remained there until the fall of 1929 when Gibbon's Battlefield and Steel Creek ranger districts were combined to form Wisdom Ranger District and Ramsey moved his headquarters to the town of Wisdom. Ramsey remained district ranger until 1940. [7]

The Forest Service administrative presence provided protection for the national monument. To NPS inspectors in the 1930s, the unoccupied ranger station detracted from the historical integrity of the battlefield. But to visitors in the previous two decades the government buildings may have contributed something to the place's charm. When it was occupied, the ranger station was landscaped with flower beds and a public drinking fountain and the lawn in front of the house was fenced and well tended. Local writer Ella C. Hathaway, describing the Big Hole section of the designated scenic route known as the Park-to-Park Highway in 1919, commented that "one of the beauty spots along the route is the ranger station at the Gibbons battlefield." The government, she noted, had "extensive plans for making this popular resort even more popular." [8]

|

| Ranger Marshall Ramsey, who occupied the Gibbon's Battlefield Administrative Site and Ranger Station in the late 1920s. Courtesy National Park Service, Big Hole NB, n.d. |

Some time between 1912 and 1919 the Forest Service built a summer cottage in Battle Gulch for Tom C. Sherrill, a former Bitterroot volunteer and caretaker of the battlefield. Sherrill developed a rapport with visitors to the national monument, regaling them with his own colorful stories of the battle. He and his family spent many summers at the battlefield, housed in what Ella Hathaway described as "one of the coziest bungalows in the hills." [9] Sherrill "retired" about 1923. Assistant Forester Will C. Barnes described Sherrill's position to the War Department in 1925:

For several years we maintained a civil employee who acted as guide to the field but for want of funds we were forced to drop him about two years ago. He was one of the survivors of the battle and told a very good story to the visitors. [10]

There were proposals to reinstate this position but nothing came of it. With improvements in communications and transportation, the trend in the Forest Service was toward consolidation of ranger districts and reductions in the number of summer employees or "forest guards." One official suggested that the battlefield caretaker position "would be a very nice assignment for some ranger who is approaching retirement age, and might be provided for in that way." But the caretaker's cottage remained empty. [11]

Visitor Access and Use

Access to this remote location improved in the years after the national monument's establishment. About 1915, a graded road was completed from the Bitterroot Valley over the Sapphire Mountains by way of Gibbons Pass to the Big Hole, and south through the Big Hole to Dillon. It was designated the "Park-to-Park Highway" connecting Glacier and Yellowstone national parks. The original location of the road brought it down the left bank of Trail Creek to a point just west of the battlefield and ranger station where it crossed the creek, climbed the bench, and continued east to Wisdom. [12] The road brought the battlefield within easy weekend distance of Missoula, the Bitterroot Valley, Helena, Butte, Deer Lodge, and Dillon and made the site a popular destination for picnics and overnight camping trips. By 1919, the Forest Service had installed outdoor fireplaces for the use of recreationists. [13]

Accurate statistics on the visitation in this era do not exist. The Forest Service placed a guest register at the national monument some time before 1925, but no visitor tally or compilation of registered names has been found. In a 1925 memorandum, one Forest Service official noted that "about 3500 people registered there this year, which probably is somewhere between 50 and 70 per cent of the actual number of visitors." [14] In 1932, Forest Supervisor Alva A. Simpson provided the following remarks on visitor use:

The Battlefield National Monument attracts a considerable number of visitors each year. Many of them camp for from one night to a week, since there is good fishing and other recreational attractions. Annually, one and one-half standard registration books are filled by visitors. These books have room for 2000 signatures and this indicates that not less than 3000 people register. Assuming the registration is 75 per cent, about 4000 people visit the Battlefield each year. Probably 15%, or 600, camp overnight or longer. It is evident that use is heavy and that our facilities are woefully inadequate for proper sanitation, fire protection, or comfort of the visitors. [15]

Estimates of visitor use remained about the same through the 1930s. In 1935, Forest Supervisor E. D. Sandvig stated the number as 3,000 to 4,000 people annually. [16] In 1939, the first year in which monthly travel statistics were kept, the NPS recorded a total of 4,005 visitors – more than 1,000 per month in July, August, and September, 450 in October, and 200 in November. [17] These numbers corroborate the earlier Forest Service estimates.

|

| Visitor register at Soldier's Monument, 1920. Courtesy of U.S. Forest Service. |

Recreational Development

Recreational development at Big Hole National Battlefield was made in response to local demand, but it also reflected broader patterns in national forest administration. Throughout the West, recreational use of the national forests increased dramatically with the spread of the automobile and the growth of a highway system. The Forest Service began to weigh aesthetic forest values against the dollar figures attached to timber sales, mineral leases, and grazing permits. Such a reorientation, Chief Forester William B. Greeley explained in 1924, was consistent with the Forest Service's goal of managing the forests for "the greatest good of the greatest number over the long run." Greeley emphasized that the Forest Service was responding to popular demand. "The American people," he wrote, "have taken possession of the National Forests as one of their great playgrounds." [18]

The Forest Service had good reasons for welcoming recreational use of the forests. One reason was to obtain broad-based political support for the development of the forests. Public demand for access to the forests translated into federal dollars for road construction, which in turn increased the value of all other natural resources with which the forests were endowed. Another reason was the establishment of the National Park Service in 1916. The creation of this agency gave a considerable boost to the national park movement. Since most national parks were created from lands in the national forest system, the Forest Service found itself in an interagency struggle over land. The Forest Service promoted recreational use of the national forests partly to squelch the argument that the NPS was uniquely suited to manage lands for public recreation.

The Forest Service now set aside a certain portion of funds for recreational development. In the 1920s these funds were supplemented – often surpassed – by contributions from local communities and organizations. Still, they represented a beginning for recreation funding. An important part of recreational development was recognizing the need for planned campgrounds at all. The purpose of campgrounds was to concentrate campers in prepared areas and minimize their impact on the forest.

|

| Picnickers on Battle Mountain, overlooking the Encampment Area and the troop withdrawal area. Courtesy National Park Service, Big Hole NB, n.d. |

Campers at Big Hole Battlefield National Monument used two sites in 1925: one directly uphill from the national monument fence, the other farther uphill above the road. The Forest Service had installed fireplaces, garbage cans, and two toilets, the latter inside the battlefield enclosure. [19] Forest service officials found two shortcomings with the existing facilities. First, they needed more fireplaces, garbage cans, and water spigots to accommodate the large number of people. Second, they wanted to move things around so that each campsite would be more self-contained and so that the whole camping area would be less conspicuous in relation to the battlefield. [20]

Improvements were slow to happen in part because the Forest Service tried unsuccessfully to persuade the War Department to bear some of the cost. [21] In 1930, Assistant Regional Forester M. H. Wolff directed Forest Supervisor J. C. Whitham to prepare a comprehensive recreational plan for the battlefield. Given the campground's popularity and close proximity to a "historical attraction," Wolff thought the campground development should receive "high priority" for funding. "Is there not opportunity to expand the camp space in a northerly or northeasterly direction from the ranger station," Wolff prodded, "perhaps even going down upon the flat below the site of the monument, if that is not too moist during the usual season of camping and picnicking." [22] Two more years passed before the Forest Service completed the recreational plan.

The projected improvements were extensive. In a 1931 draft plan, Ranger Ramsey and Forest Supervisor Whitham proposed to develop seventeen campsites, each with stove and table, at two locations that they called the upper and lower campgrounds. In addition they wanted seven garbage pits and two new toilets. [23] In their final "Unit Recreational Plan," Whitham and Ramsey reduced the number to ten: five in the timber above the national monument and five in the willows below the national monument. These campsites would be "adequately screened from each other." Existing toilets were to be improved "to make fly-proof and sanitary." Water supply for the upper campground would come from the existing pipe line, and for the lower campground from wells or pitcher pumps. The area in front of the entrance to the national monument would be devoted to parking and tent space for overflow crowds. [24]

The Forest Service never implemented the recreational plan, probably due to the fact that the five-acre national monument was transferred to the National Park Service the following year. Forest service officials insisted there was still a great need for campground improvements, and recreational development became the major issue between Forest Service and NPS officials in the transition years from 1933 to 1939.

Resource Protection

Its enthusiasm for recreational development notwithstanding, the Forest Service had little experience protecting historic sites or interpreting historic resources for the public. The Forest Service's accomplishments in this field at Big Hole Battlefield National Monument were principally due to the personal initiative of three individuals who took a keen interest in the site. These individuals were battle veteran and caretaker Tom C. Sherrill, District Ranger Marshall G. Ramsey, and Assistant Forester Will C. Barnes.

Sherrill was an old man by the time he assumed the role of caretaker at the battlefield. He had a keen memory and could recite many details of the battle. If some people questioned the accuracy of what he said, others were willing to accept him as a reliable eyewitness or even an authority. Sherrill gave many visitors guided tours of the battlefield. He sometimes shared his personal collection of artifacts from the battle, which included his own hat with a bullet hole, a bloodstained deerskin sleeve torn from the jacket of a dead Nez Perce, and a scalp-lock taken from another Nez Perce killed on the battlefield. [25]

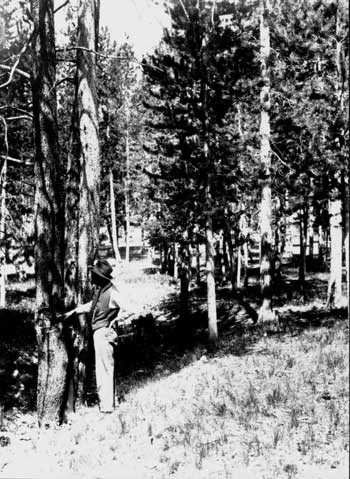

|

| Forest Guard Tom Sherrill pointing to spot on tree where souvenir hunters removed bullets. Courtesy National Park Service, Big Hole NB, n.d. |

Sherrill staked the ground where he recalled certain people to have been killed, wounded, or buried. Eventually he prepared a series of texts, which were printed on white signboards and placed at appropriate locations around the site. These texts had a rustic character and were written utterly from the soldiers' point of view. For example, one sign noted "Where the Indian was killed that craweled the closest to our breast works," and another "Where the Indian was killed that sang his death chant for thirty minutes before he died." Some displayed a gritty sense of humor: "Jack Bear held this riffle pit for thirty-six hours, thru the fight, he was well entertained by Indians under the hill." Significantly, some of the signs marked the spot where soldiers were buried. There were some 37 signs altogether. Although they were removed in the 1930s, the locations and texts of each sign were preserved in a memorandum prepared by Sherrill and Ranger Ramsey titled "Points of Interest," dated October 7, 1921. [26]

Sherrill and Ramsey also sought to protect the battlefield from relic hunters. In 1928, several years after Sherrill's position was eliminated, Ramsey built a rough picket fence of lodgepole pine around portions of the battlefield, and a pole fence around the rifle pits. Photographs of these improvements show that they were highly intrusive on the scene. With no caretaker at the site, however, Ramsey believed the fences were necessary to protect the resources. [27]

The third official to take an interest in the battlefield was Assistant Forester Will C. Barnes, a former cattleman and veteran of the campaign against the Apaches in Arizona in the 1880s. Having risen to one of the senior positions in the Forest Service, Barnes developed an interest in the national monument after taking the opportunity to inspect the battlefield on a trip to Montana in 1925. Upon returning to Washington, D.C., Barnes served as the Forest Service's liaison with the War Department. His chief interest was to recover and rehabilitate the 12-pounder mountain howitzer used by Colonel Gibbon's command.

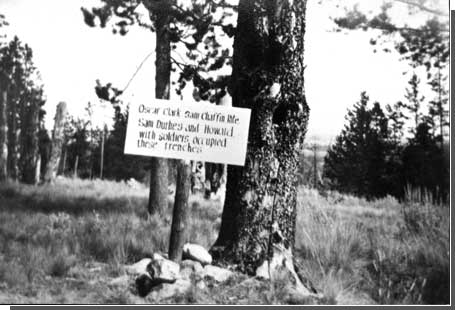

|

| U.S. Forest Service interpretive sign. Courtesy National Park Service, Big Hole NB, n.d. |

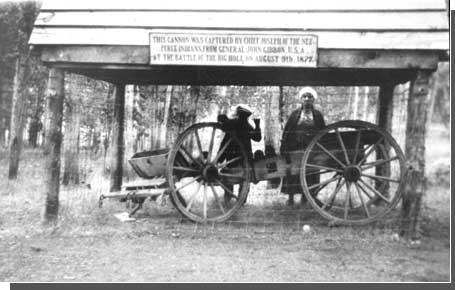

According to the best information available in the 1920s, Nez Perce warriors had overrun the howitzer and had disabled the weapon by hacking spokes from the wheels and rolling the carriage into the river. Some weeks after the battle in the fall of 1877 a party from Deer Lodge hauled the cannon out of the river and took it back to Deer Lodge. The wheels were repaired and for many years the cannon sat in front of the State Penitentiary in Deer Lodge. In 1923, Governor Joseph M. Dixon ordered the cannon returned to the battlefield. [28]

During 1926, Assistant Forester Barnes corresponded with Maj. L. D. Redington of the Quartermaster Corps, U.S. Army, as to the proper repair and maintenance of the cannon. Redington provided specifications and material for painting the metal and wood parts of the cannon based on the War Department's experience with preserving cannons in the national cemeteries and national military parks in the East. Redington also facilitated a transfer of $500 from the War Department to the Forest Service for construction of a wood shelter for the cannon and a museum building. The transfer of funds was accomplished in 1928. [29]

The museum building was built in 1928 or 1929. Its walls were made of lodgepole pine peeled logs and the gable roof was covered by hand-split cedar shakes. Measuring 14 by 18 feet, the building housed the cannon as well as other relics of the battle. In 1929, an inspector reported that the building conformed "very well to the surroundings," and that local citizens had agreed "to return articles in their possession which will add great interest to the collection." [30]

No sooner was the museum built than the Forest Service had another resource at risk. The lodgepole trees around the Siege Area were attacked by insects. By 1932, some 80 "historic trees" were dead. [31] The trees were significant because they dated back to 1877 and related to the combatants' positions; many also bore battle scars. Three years later, Ranger Ramsey and Forest Supervisor E. D. Sandvig estimated the number of insect-killed trees in the area at 2,000. The dead trees occasionally toppled over, presenting a hazard to visitors. Moreover, they were aesthetically displeasing. To Sandvig, the dead trees presented "a picture of untidiness and forlorness [sic]," and needed to be cut down and removed. [32]

Removal of the dead trees was no ordinary salvage logging operation, however, because the trees in the Siege Area constituted historic resources. Many bore scars from the hail of bullets during the battle. Souvenir hunters also saw them as historic objects; they had been chopping away at the trees for years, taking splintered sections out of the trunks and carrying them home for use as desk fixtures or mantle ornaments. [33]

|

| Shelter built for mountain howitzer and limber. Courtesy National Park Service, Big Hole NB, n.d. |

The "Unit Recreational Plan" of 1932 stipulated that "historic trees that are killed will be taken down and sections preserved in the Museum." [34] Since the plan was never formally adopted, however, Ramsey readily deviated from the policy in 1936 when historian Lucullus V. McWhorter asked to be sent a splintered section of the tree that had sheltered Nez Perce warrior Peo Peo Tholekt. Ramsey packaged and shipped the chunk of tree to Forest Service employee K. D. Swan of Missoula for McWhorter's son to pick up and take to McWhorter's home in Yakima. Although McWhorter purportedly wanted the section for safe keeping, his motivation hardly differed from that of other collectors who took an avid interest in the battle. [35]

Unit managers would later describe the entire timbered area as a historic resource because it had provided a strong defensive position to which Gibbon's command had retreated in the course of the battle. It is worth noting that managers in the 1930s regarded the trees as objects or historic artifacts rather than part of a historical landscape.

|

| Yellow Wolf, a veteran of the battle and key informant on the Nez Perce positions. Courtesy National Park Service, Big Hole NB, n.d. |

Interpretation: The McWhorter Era

Lucullus V. McWhorter brought to light the Nez Perce side of the battle just when it was in danger of dying with the last of the Nez Perce war veterans. On five separate occasions between 1927 and 1937, McWhorter visited the Big Hole Battlefield with his Nez Perce friends and elicited their recollections of what happened on August 9, 1877. Accompanied by a surveyor, McWhorter and the Nez Perce veterans staked the battlefield in 1928 and again nine years later. The staking superseded the earlier staking done by Tom Sherrill and greatly amplified the Nez Perce perspective of the battle. McWhorter also presented a Nez Perce "voice" in two books that were based on his extensive interviews with tribal members: Yellow Wolf: His Own Story (1940) and Hear Me, My Chiefs! Nez Perce History and Legend (1952).

McWhorter was a cattle rancher and historian who had an abiding interest in Indians. According to his biographer, McWhorter's reading of frontier history "convinced him that the American Indians had been 'cold-decked' . . . and their heroic defense of their homes and families constituted a true American epic." Moving his family from Ohio to central Washington in 1903, McWhorter sought to befriend Indians and to write their story. His early endeavors focused on the Yakama tribe who lived near his ranch outside of North Yakima, Washington. In 1907 he met a Nez Perce named Hemene Mox Mox, or Yellow Wolf, who had just finished his seasonal job in the nearby hop fields and was returning to his home on the Colville Reservation. McWhorter's friendship with Yellow Wolf became his point of entry to the Nez Perce people. [36]

Over the years McWhorter struck up friendships with a number of Nez Perce veterans of the War of 1877. On the fifty-year anniversary of the war, he made his first automobile trip to the Montana battlefields accompanied by Yellow Wolf, Peo Peo, and Sam Lott (Many Wounds). They camped at the Big Hole battlefield. McWhorter's biographer has described this first visit:

Since 1908, McWhorter had been listening to veterans describing the Battle of the Big Hole; now everything was exposed with clarity. There was the open hillside, surrounded by timber, where the bands had kept the horse herd. Below, along the base of the hillside, ran the meandering stream – the North Fork of the Big Hole – which separated the horse pasture from the tipi village. Across the north side of the river and upstream from the encampment, rose the low timbered hill where the warriors surrounded Colonel John Gibbon's troops and held them under siege. A little farther up the drainage, Peo Peo showed McWhorter where he had helped capture Gibbon's mountain howitzer. He found the spot where he had buried the howitzer barrel, but it no longer was there. As McWhorter looked to the south, he could see the open country across which the retreating bands escaped with their wounded. With this on-site investigation of the Battle of the Big Hole, McWhorter could document individual acts by warriors, and recreate a clear and comprehensive historical picture of the battle from the Nez Perce point of view. [37]

The party did not have time to stake the battlefield on this brief visit. (Later in the trip, at the Bear's Paw Battlefield, the party did place stakes to mark the veterans' memories of events.) The following July, however, McWhorter returned with Peo Peo, Sam Lott, another veteran named Black Eagle, an unnamed surveyor, and Seattle sculptor Alonzo S. Lewis. Three other veterans who had hoped to go (Joe Albert, Jefferson Green, and Yellow Wolf) did not make the scheduled rendezvous in Lapwai. On this trip the party staked and surveyed the entire battlefield including the Nez Perce Encampment Area, and it placed a small memorial shaft with a bust of Chief Joseph on the head near the soldiers' monument. [38]

McWhorter returned to the Big Hole battlefield for a third time in July 1930 accompanied by Yellow Wolf, Sam Lott, Peo Peo, Lewis, and his son Virgil. As his biographer explains, McWhorter was interested in recovering more details about the battle, believing that "Indian narrations are entirely different from that of the average white person." It was McWhorter's experience that an Indian informant "seldom branched from the line that he may have in mind, but later some trend of mind might bring it to him." Consequently, each new visit to the battlefield elicited new facts from each individual, and "then comes another enstallment [sic]." [39] Moreover, McWhorter made repeated visits with the aim of acquiring an understanding of the battle from many individual points of view.

McWhorter made yet another trip in August 1935, this time with Sam Lott and Chief White Hawk. The main purpose of the trip was to restake the Bear's Paw battlefield. The original stakes from 1927 were in poor condition. The local chapter of the Lion's Club in nearby Chinook, Montana raised funds to defray the travel expenses of the two Nez Perce veterans, and a Blaine County engineer named Noye helped with the surveying. [40] While visiting the Big Hole battlefield on this trip, McWhorter was saddened to find that the tree which sheltered Peo Peo in 1877 had died since their previous visit. It was after this trip that he asked Ranger Ramsey to preserve a section of the tree for him.

|

| Chief Joseph monument placed at Big Hole Battlefield in 1928. Courtesy National Park Service, Big Hole NB. |

Yellow Wolf, Peo Peo, and Sam Lott all died in the following months. Perhaps it was this news, which McWhorter relayed to Ramsey the following August, that prompted the ranger to urge McWhorter and his Nez Perce friends to make yet another trip to the battlefield and stake some additional ground. "There are many things we talked about," Ramsey wrote, referring to the original staking in 1928, "that I figured at the time I would never forget, but as I try to recall some of the instances that occurred in different places I find that by not writing them down they are not as clear to me now as they could be." [41]

To this letter McWhorter replied:

I can get two of the warriors, and a first class interpreter, one who is deeply interested in the work that I have on hands [sic], who will go with me and point out the places of particular historic interest, both in the lower meadow where the village was attacked, as well as where the howitzer was captured, and also confirm the mistakes pointed out to me by both Peo and Yellow Wolf, in the staking of the park field, relative to the Indians killed there. I am satisfied that Mr. Sherrill had those stakes incorrectly placed. [42]

Significantly, McWhorter saw the role of his Nez Perce informants as not merely to augment, but to correct or reinterpret information that had come from white participants in the battle. McWhorter's efforts at Big Hole supported his larger goal to retell the story of the Nez Perce War from an Indian point of view.

|

| Peo-Peo Tholekt, another veteran who helped mark Nez Perce positions on his return to the battlefield in 1928. Courtesy National Park Service, Big Hole NB, n.d. |

Ramsey was supportive. On the occasion of McWhorter's earlier visits in 1927 and 1928, Ramsey had given the party a hearty welcome. Although he did not see McWhorter and his Nez Perce companions in 1930 or 1935, he put some effort into arranging the last trip in 1937. Ramsey tried to obtain financial support from both the local Lions Club and the National Park Service before securing private donations through the Big Hole Road Association. With the help of the "wide awake women" of this organization, Ramsey sent McWhorter a check for $75 in July to pay expenses to the battlefield. [43] McWhorter returned in September 1937, accompanied by two elderly Nez Perce, Camille Williams and Phillip Williams, to restake the battlefield and to map various points of interest. [44]

By 1937, McWhorter had been collecting material on the Nez Perce for thirty years. Although he had no official capacity, he had become a major asset to the national monument. Forest Supervisor W. B. Willey, anticipating Park Service administration of the site, informed Yellowstone Superintendent Edmund B. Rogers of McWhorter's efforts in December 1936:

Mr. McWhorter is in the last stages of preparation on a book delineating the details of the Nez Perce War. He has made his home among or near the Nez Perce Indians for many years and is in possession of facts that probably can never be gathered again. . . . Ranger Ramsey tells me that Mr. McWhorter speaks the Nez Perce language fluently besides having acquired a great deal of background and confidence while preparing his manuscript among the Indians. It is my opinion that you will be taking advantage of a rare opportunity if you include in your program the surveying and marking of the Big Hole Battlefield with the help of this historical researcher. [45]

McWhorter published Yellow Wolf: His Own Story in 1940. He died in 1944. Another book, Hear Me, My Chiefs! Nez Perce History and Legend was published posthumously in 1952.

McWhorter's contribution was enormous. Without his organizing efforts it is doubtful whether any Nez Perce war veterans would have returned to the battlefield, much less imparted their knowledge to non-tribal members in a way that could be preserved for posterity. McWhorter recovered the voice of the Nez Perce in the 1920s and 1930s just as the last of the warriors were dying. As a result, recollections of Yellow Wolf, Peo Peo, and other Nez Perce came to inform interpretive efforts at the battlefield just as much as recollections of Tom Sherrill and written accounts by Colonel Gibbon, Amos Buck, Will Cave, and other white battle veterans.

The Nez Perce "voice," literally engraved in many of the signs around the battlefield, drew the attention of the battlefield visitor to the village Encampment Area where so many Nez Perce women and children had lost their lives in the initial attack. This was, of course, a section of the battlefield that greatly impressed "tourists" soon after the battle – it featured prominently in Granville Stuart's sketch of May 1878, and in Andrew Garcia's haunting memories of his visit to the battlefield later that same year. Yet for more than fifty years after the Nez Perce surrender, the Big Hole battlefield was commemorated primarily through the placement of a war memorial to the U.S. soldiers. The soldiers' monument as well as the many signs and splintered trees throughout the Siege Area put the interpretive focus squarely on the plight of the white soldiers and volunteers. Although the soldiers' monument would continue to be a focal point for picnics, reunions, and commemorative events (often involving relatives of the Bitterroot volunteers), these activities gradually became more muted. As early as 1935, one Forest Service official urged that "purely recreation activities, particularly those of a more frivolous nature such as organized group picnics and camping," should be discouraged. Rather, it was "fitting and essential that an air of quiet dignity be preserved about it." [46]

It is not too much to say that McWhorter and the Nez Perce veterans preserved what was most vital to the national monument not just for the Nez Perce people but for the nation. Even while the Nez Perce War was in progress the renegade bands had aroused the sympathy of many Americans, and their long fighting retreat through Idaho and Montana had long since entered the annals of American history as one of the epic tragedies of Indian defeat. As one travel magazine writer described the visitor experience at the Big Hole battlefield some years later, "There slumbers a valley in southwestern Montana so impregnated with silence that the spirit of the visitor seems to hear sorrow...as if the sound waves of a once great misery enacted here moved on but left sad ghosts behind." [47]

Transfer to the National Park Service

On July 28, 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order No. 6228, transferring jurisdiction of the five-acre national monument from the War Department to the National Park Service. The executive order placed a total of 48 national monuments, battlefields, and military parks in the national park system. Most of these sites related to the Revolutionary and Civil wars and were located in the East. Only one site – Big Hole Battlefield National Monument – commemorated a battle fought in the West. It would be joined by a second, the National Cemetery of Custer's Battlefield Reservation, seven years later. Both of these battlefields of the Indian Wars were relatively inaccessible in the 1930s, and of the two Big Hole was the less renown. [48]

Following the usual procedure when a national monument was proclaimed in a remote location, the NPS assigned the area to a "coordinating superintendent" in the nearest national park. This was Yellowstone Superintendent Roger W. Toll, whose headquarters at Mammoth Hot Springs was a day's drive from the battlefield. It seems that Toll had but one opportunity to visit Big Hole Battlefield National Monument before his tragic death in an automobile accident in New Mexico in February 1936. Toll sent Ranger Maynerd Barrows to inspect the national monument in August 1935 – two years after the transfer. His report on Barrows' inspection to Forest Supervisor E. D. Sandvig, dated August 8, 1935, is the earliest known document by an NPS official concerning the Big Hole battlefield. [49]

Superintendent Toll's memorandum offered the first clues as to changes of management that the Forest Service could expect following the transfer of the five-acre national monument. Toll provided an itemized list of recommendations:

1. The dead trees in and around the national monument should be cut at ground level, sawed in 15-inch lengths, and split in four blocks. Sections containing bullet marks should be preserved for museum pieces.

2. Any historic trees still standing should be left if they had a good chance of remaining upright for a number of years.

3. The two old latrines just outside the national monument should be removed, since adequate toilet facilities were provided in the Forest Service campground.

4. The bridge near the entrance to the national monument should be repaired.

5. The NPS would try to employ a summer caretaker, who would be quartered in the Forest Service caretaker's house. [50]

Toll's memorandum indicated that the NPS was interested in the land surrounding the five-acre site. It shared the Forest Service's interest in providing visitor facilities. Clearly, on the basis of Toll's memorandum, the Forest Service had to redefine its role in managing the area around the national monument.

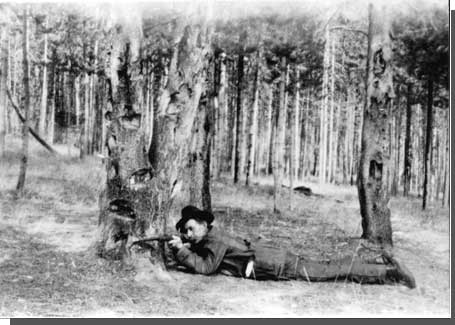

|

| Forest Guard Tom Sherrill demonstrating soldier's position in the Siege Area. >One of the last surviving veterans of the battle, Sherrill served as battlefield custodian, circa 1915-1923. Courtesy National Park Service, Big Hole NB, n.d. |

Local Forest Service officials, meanwhile, were impatient for the NPS to do more – or at least they wanted the two agencies to negotiate what kind of presence the Forest Service would maintain there. The general appearance of the place had declined since the abandonment of the ranger station in 1929. The recreational plan completed in 1932 had never been implemented. By 1935, the ranger residence and outbuildings were partially dismantled and the structures that remained were supposed to be burned down. Forest Supervisor Sandvig described the "deplorable condition" of the station to the regional forester: "It now has the appearance of an abandoned dryland farmers' abode and presents a despicable picture to all who view it." [51] From the standpoint of local Forest Service officials, it was an awkward time to find the battlefield in limbo between two agencies.

After receiving Superintendent Toll's memorandum, Forest Supervisor Sandvig consulted with the regional forester on the prospect of an NPS employee occupying the caretaker residence. He had no objection other than the fact that he had wanted to replace the cabin with a log building farther away from the national monument. Now it seemed necessary to coordinate with the NPS before proceeding further with his improvement plan. [52]

Superintendent Toll also expressed the need for coordinated planning. In a second letter to Sandvig on August 17, 1935, Toll noted the Forest Service's longstanding effort to work for the preservation of the area even though it was not under the direct jurisdiction of the Forest Service. "We appreciate deeply the fact that you are continuing this same service now that the jurisdiction of the area has been transferred to the National Park Service," he wrote, "although our Service has as yet been unable to take any active part in administering the area." [53]

At the same time that Toll and Sandvig were establishing a connection between their two agencies, the Forest Service was moving a crew of Civilian Conservation Corps enrollees into the battlefield area to "do a general cleanup job." Toll urged Sandvig to make sure that any artifacts discovered during the cleanup were turned over to the government. "It is suggested that relics be adequately labelled together with the name of the man by whom it was found and turned in," Toll wrote. [54]

In the following months, Forest Service officials sensed that it was a propitious time to suggest boundary changes for the national monument. Ranger Ramsey advised his superior that he would be in favor of extending the boundaries of the national monument to the north, south, and west – all within the national forest. He pointed out the importance of the Nez Perce Encampment Area but noted that the land currently belonged to the Huntley Cattle Company and would have to be purchased. The landowner had cut hay in this area for a number of years and had used it for pasture since 1932. [55]

Assistant Forester V. T. Linthacum offered his views on the boundaries after inspecting the site with Ramsey in September 1935. Like Ramsey, he was in favor of transferring national forest land to the national monument so that the NPS would be responsible for all recreational development associated with the battlefield. "It all forms a single natural unit," he explained. "National Forest recreation should be found elsewhere." As for including the Nez Perce Encampment Area, Linthacum advised that that should be left up to the NPS. [56]

Linthacum offered more pointed remarks in a second memorandum. He believed the Forest Service should completely withdraw from the old Gibbon's Battlefield Administrative Site so that the two agencies would not be in each other's way. "The present monument area is entirely too restricted, both for the purpose intended and as an inducement to the Park Service to make something out of it and give it proper administration," he wrote. "If the Park Service will propose to make this a National Monument that we can all be proud of let's help things along in every possible way which does not involve or seriously inconvenience our Forest administration." [57] Forest Service actions after 1935 followed in this spirit – the following spring, Forest Supervisor Sandvig directed Ranger Ramsey to remove remaining improvements and Forest Service signs as rapidly as possible. [58]

As Forest Service involvement in the site waned, National Park Service development did not take place the way Forest Service officials had hoped and anticipated it would. Despite an enlargement of the site in 1939, Big Hole Battlefield National Monument would acquire the dubious honor of becoming a backwater unit in the national park system, a "sleepy hollow" in the words of a later superintendent. [59] That disappointment notwithstanding, the transfer of Big Hole National Monument to the Park Service was a model of interagency cooperation. In contrast to the larger scheme of Park Service-Forest Service competition in this era, Beaverhead National Forest officials hastened to facilitate a turnover of land, improvements, and visitor services to the other agency. NPS intentions for the site, and the factors that would make Big Hole of low priority in the national park system, are detailed in Chapter Four.

|

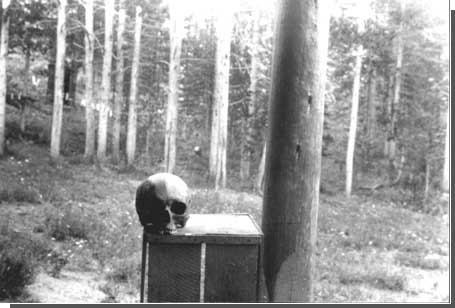

| Human skull found in Battle Gulch. Courtesy National Park Service, Big Hole NB, n.d. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

/chap3.htm

Last Updated: 22-Feb-2000