|

BIG HOLE

Commemoration and Preservation: An Administrative History of Big Hole National Battlefield |

|

Chapter Two:

Administration under the U.S. War Department (1883-1910)

Federal recognition and administration of Big Hole battlefield developed slowly in the decades after the battle. A monument to the U.S. soldiers was erected at the site in 1883. A bill to establish a national park was considered in 1906. After the Antiquities Act of that year, officials in the War Department, the U.S. Forest Service, and the General Land Office moved cautiously to set aside a small area under executive order.

Early Interpretation of the Battle

The Battle of the Big Hole generated immediate and widespread interest. Even more than the Nez Perces' long retreat over the Bitterroot Mountains into Montana, the hard-fought battle turned the Nez Perces' struggle into an epic, sensational event. That these Indians had been ambushed in their tepees and had still managed to escape seemed to confirm the military genius of the Nez Perce chiefs. Even as the war continued, newspaper writers spawned the legend of Chief Joseph's superb military leadership. The timing of the battle was important, too. "Coming within fourteen months of the Custer Massacre," historian Merrill D. Beal has written, it "aroused the whole nation and attracted the attention of the world." Some observers predicted that the Nez Perces' resistance could lead to a general Indian uprising. [1]

Survivors of the Battle of the Big Hole began to interpret what had happened as soon as the campaign was over. Colonel Gibbon wrote an "after action" report of the battle on September 20 from his hospital bed in Deer Lodge, detailing his actions and those of his adversary. General Howard also filed a report that fall. Gibbon and Howard each described the encounter in retrospect – Gibbon in an article published in Harper's Weekly in 1895, Howard in Nez Perce Joseph (1881) and again in My Life and Experiences among Hostile Indians (1907). Several soldiers and volunteers published accounts of the battle in various national magazines during the 1880s and 1890s. Even if these many accounts by survivors of the conflict varied in detail and reliability, they all contributed to making the Battle of the Big Hole perhaps the most well-documented battle of the Indian Wars.

No sooner was the war over than contemporaries sought to draw moral lessons from the episode. A New York Times editorial charged that "the Nez Perce War was, on the part of our government, an unpardonable and frightful blunder." The Nez Perce had been "goaded by injustice and wrong to take the war path." [2] Chief Joseph corroborated this view. Following his exile to Oklahoma, he recounted his people's story to a writer who published it in The North American Review in 1879. [3] Significantly, the piece was titled "An Indian's View of Indian Affairs" – it used the story of the Nez Perce War to draw larger lessons about federal Indian policy. Similarly, when members of Congress held hearings on the conduct of the Nez Perce War in 1878, they asked Colonel Gibbon not only to provide analysis of the Army's poor showing in the battle and the campaign, but to expand on the problems of federal-Indian relations. [4]

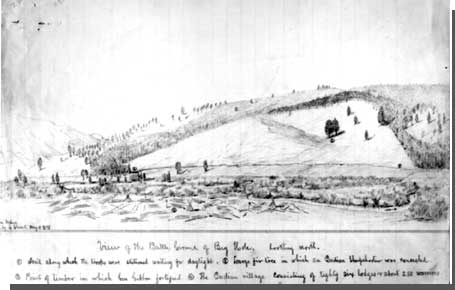

The lively interest in the Battle of the Big Hole extended to the battlefield itself. Montana pioneer Granville Stuart visited the battlefield on May 11, 1878, and made two sketches of what he saw. The first was a panorama looking toward the mountainside, with numbered annotations describing the soldiers' approach, the Nez Perce Encampment, the Twin Trees, and the Point of Timber to which the soldiers fell back. Stuart must have been accompanied by a veteran of the battle when he made this drawing. His second drawing was an artistic rendering in birdseye perspective. The litter of human skulls, horse skeletons, and tepee poles in the foreground of the picture suggested a moral censure of the attack on the Nez Perce village – a noteworthy perspective for a white resident of the territory. [5] It contrasted sharply with contemporary views of the Battle of the Little Bighorn that venerated Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer and his men as martyrs in the cause of westward expansion. [6]

|

| Sketch of Big Hole Battlefield by Granville Stuart, May 11, 1878. Courtesy Montana Historical Society, Helena, Montana. |

At least two schematic maps of the battlefield were made by or with the help of participants in the battle. Pvt. Holmes L. Coon located the main features of the battle in a crude sketch. And one L. T. Henry made a map of the site based on notes and measurements provided by Capt. J. M. T. Sanno, a battle veteran. The latter was presented to the Historical Society of Montana by the Helena Herald on September 2, 1888.

The Soldiers' Monument

In 1883 a granite monument was erected at the battlefield to honor the soldier dead. Who initiated the project and precisely what the monument meant were details soon forgotten. Official correspondence in the early 1900s – when the soldiers' monument was already nearly twenty years old – disclosed that authorities in the War Department were uncertain whether the monument doubled as a grave marker or not. In the absence of documentation, it was assumed that it did not.

The idea for the soldiers' monument may have originated with Colonel Gibbon. The colonel recommended a number of his men for Medals of Honor, and years after the battle he wrote letters in support of the Bitterroot volunteers' claims for compensation for their service. Together with General Howard and Col. Nelson Miles, he also took an interest in the cause of returning the exiled Nez Perce to their homeland. In addition to these activities, it appears that Gibbon first suggested the idea of a monument to commemorate the slain members of his command at the Battle of the Big Hole. [7]

On February 28, 1882, Secretary of War Robert T. Lincoln authorized the expenditure of $800 for the placement of a granite monument on the Big Hole battlefield. The expenditure came from incidentals of the quartermaster's department for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1882, and did not require an act of Congress. [8] The six-ton monument was cut in Concord, New Hampshire, shipped by railroad to Dillon, and hauled by ox teams from there to the battlefield. It was erected in September 1883 by a detachment of soldiers from Fort Missoula, under the command of Capt. J. T. Thompson, Third Infantry. [9]

Cut in the shape of a stout obelisk and bearing an inscription that honored the U.S. soldiers who fell in the battle while making no mention of Nez Perce casualties, the "soldiers' monument" conveyed a nationalistic sentiment of honorable sacrifice. The dimensions and placement of the soldiers' monument near the Siege Area were suggestive of a large, common gravestone. Indeed, like the granite obelisk placed at the Little Bighorn Battlefield in 1886, it bore the names of all the officers and enlisted men killed in the conflict. Yet the soldiers' monument made no specific reference to soldiers' graves.

In the years following the placement of the soldiers' monument, the Big Hole Valley grew less isolated. Homesteaders moved into the valley beginning in May 1882, taking up claims along the river and creeks where they could grow hay and raise cattle. Small ranches soon dotted the length of the Big Hole and the towns of Wisdom and Jackson Hot Springs sprang to life. [10] Transportation in the valley remained primitive; one of the early wagon roads originated from settlers using the wheel ruts made by the wagon that had carried the granite monument into the valley in 1883. As the Big Hole became settled, tourists frequented the battlefield in growing numbers. The soldiers' monument served to mark the site years before there was any official interpretation or protection of the battlefield.

One person who visited the soldiers' monument, Lt. P. Murray, 3rd Infantry, was disturbed by what he found. "Relic hunters," Murray complained, were defacing the monument. In a letter dated February 6, 1895, Murray stated that "nearly all the corners are broken off, the edges being similarly attacked." He also found that the pine trees around the Siege Area were being "cut to pieces by people hunting for bullets." [11] Murray's letter was forwarded to Capt. George S. Hoyt, assistant quartermaster in Helena. In June 1895, Hoyt submitted an estimate for the erection of an iron fence to enclose the soldiers' monument and protect it from further vandalism. [12] No appropriation was made at this time.

On February 8, 1900, the Senate passed a resolution requesting the Secretary of War to ascertain what action "has been taken or should be taken to properly mark the graves of those killed and buried on or near the battlefield, and to preserve such marks from obliteration." [13] In reply, Quartermaster General M. I. Ludington stated that "the records of this office give no information on the subject of the Big Hole battlefield, or the marking of the graves of those buried there." Ludington was only able to produce correspondence from 1882-1883 regarding the erection of the soldiers' monument and from 1895 regarding the need for a protective fence. Less than a quarter century after the battle, the administrative record of this soldiers' monument was already obscure to the officials responsible for maintaining it.

|

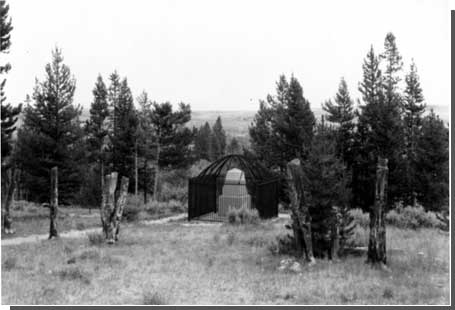

| Soldier's monument in Siege Area. The metal cage was added later to protect the monument from souvenir collectors. Courtesy National Park Service, Big Hole NB, n.d. |

A National Park Proposal and a Temporary Land Withdrawal

Between 1900 and 1910, a number of proposals were put forward to make some kind of federal reservation around the battlefield. These various proposals included a Senate resolution, a House bill, administrative actions by both the War Department and the fledgling U.S. Forest Service, and finally a presidential proclamation. The proposals languished, and the government's hesitation probably attested to continuing uncertainty about whether the site held any soldiers' remains.

The Senate resolution of February 8, 1900 requested information on whether the area was surveyed. Implicit in the Senate resolution was the idea that the government might withdraw an area of the public domain from private land entry. Correspondence between the Adjutant General's Office and the General Land Office (GLO) in March 1900 established that the sections around the monument were not yet surveyed. The latter office made a projection, based on existing surveys, that placed the battlefield in sections 31 and 32, T1S, R16W; and sections 5 and 6, T25S, R16W, Montana meridian. [14] No further action was taken.

Two years later, in October 1902, the War Department requested an update of this information. The GLO replied that the land was still unsurveyed; however, it now placed the battlefield approximately six miles southwest of the earlier location in the N. of section 24, T25S, R17W. The GLO stated at this time that it saw no reason why the land "should not be withdrawn from settlement and declared a military reservation," that is, a commemorative site under War Department jurisdiction. Still, no further action was taken. [15]

On February 13, 1906, Congressman Joseph M. Dixon of Montana introduced House Resolution 12699, a bill to create a "Big Hole Battle Ground National Park." This bill is significant as an expression of national park purposes early in the development of the national park system. In February 1906 there were less than a dozen national parks in the nation. All were nominally under the administration of the secretary of the interior, although the U.S. Army had functional responsibility for a number of them. The Antiquities Act, so vital to the expansion of the national park system in its authorization of presidents to create national monuments by proclamation, still lay four months in the future. [16]

|

| Siege Area and Soldier's Monument. Courtesy National Park Service, Big Hole NB, n.d. |

The bill provided for a reservation of 1,280 acres: the E. of sections 13 and 24, T25S, R17W, and the W. of sections 18 and 19, T25S, R16W. The bill placed the national park under the administration of the secretary of the interior, and declared that any act of vandalism toward "any monument, grave, or building, fence, or improvement" would be punishable by fine or imprisonment. The bill was submitted to the Committee on Public Lands. [17]

Secretary of the Interior Ethan A. Hitchcock suggested amending the bill so that the secretary of war rather than the secretary of the interior would administer the area. The latter official, Hitchcock explained, had "supervision of national military parks, which reserve famous battlefields, and national cemeteries, where deceased soldiers are interred." [18] These were sacred places where the nation memorialized its wars and the people expected to find a solemn kind of inspiration. National parks, by contrast, were "set aside as pleasure grounds for the use and benefit of all the people, and with a view to preserving forests, wonders of nature, etc." [19] Managing a historic place particularly if it related to war, it seemed to Hitchcock, was beyond his department's ken.

Hitchcock raised another consideration. According to the GLO, 840 acres of the area proposed for a national park were covered by three private claims. These included one patented desert land entry, one pending claim under the Desert Land Act, and one pending claim under the Homestead Act. [20] Hitchcock, therefore, proposed another amendment that would allow land exchanges between private owners and the government to restore these lands to public ownership. Meanwhile, Hitchcock took the precaution, in case the bill were passed, of directing the commissioner of the GLO to suspend all applications and entries for lands in the four sections mentioned in the bill until further notice. [21]

Forest Service Initiatives

Four months after Congressman Dixon introduced his national park bill, Congress passed the Antiquities Act of June 8, 1906. Sponsored by Congressman John Lacey of Iowa, the law was intended to protect areas of unusual historic or scientific interest. It authorized the president to proclaim such areas as national monuments. President Theodore Roosevelt immediately invoked the law to create Devils Tower National Monument in Wyoming, thereby establishing the important precedent that national monuments could encompass monumental landforms (much like national parks) as well as archeological or historic resources. Despite this action, however, there was no immediate expectation that national monuments would be administered together with national parks by one agency. That development would come many years after the creation of the National Park Service, when Executive Order 6288 consolidated national monuments, military parks, and historic sites within the national park system. [22]

|

| Lodgepole pine scarred by souvenir hunters, who cut bullets out of the trunk. Courtesy National Park Service, Big Hole NB, n.d. |

The Forest Service, newly established in 1905 as a land management agency in charge of national forests, responded quickly and aggressively to the legislation. Forester Gifford Pinchot promptly revised The Use Book, the agency's versatile little handbook of regulations and instructions for use of the national forests, to reflect the Forest Service's ability to manage such areas. The 1906 edition, issued less than a month after passage of the Antiquities Act, included the following two paragraphs on historic and scientific monuments:

All persons are prohibited from appropriating, excavating, injuring, or destroying any historic or prehistoric ruin or monument, or any object of antiquity situated on lands owned or controlled by the Government of the United States, without the permission of the Secretary who has jurisdiction over the land involved....

Forest officers should report to the Forester the location and description of all objects of great scientific or historic interest which they find upon forest reserves, and should prevent all persons from injuring these objects without permission from the Secretary of Agriculture.... [23]

Pinchot's purpose was to demonstrate that national monuments need not be transferred out of the Forest Service's jurisdiction for they would receive due consideration under national forest management. In Pinchot's haste to embrace the new legislation, these paragraphs were tacked onto the Forest Service's Regulation 43 concerning wild hay!

The Big Hole National Forest was established in November 1906. It was enlarged and renamed the Beaverhead National Forest two years later. The original national forest boundary ran through sections 13 and 24, T25S, R17W, intersecting the area withdrawn by the GLO in connection with the battleground national park bill. Consequently, the GLO brought the park proposal to the attention of the Forest Service. [24] One C. R. Pierce, a clerk in the GLO's Law Division, reported that local citizens wanted the Forest Service to protect the battlefield and the soldiers' monument from vandalism. "It seems that it can best be done," Pierce concluded, "by withdrawing the land as a National monument." [25]

The Forest Service surveyed the site, which it called the "proposed Gibbons Battle Field National Monument," during the winter of 1907-08. Forest Supervisor C. K. Wyman forwarded a map and cost estimate for improvements to Forester Gifford Pinchot on April 18, 1908. Wyman wanted to put a barbwire fence around the whole area. His estimate also carried an item for "cleaning up grounds and burning down timber." [26]

It is unclear what happened to this national monument proposal. Perhaps it was converted into an appropriation request. On January 22, 1908, Joseph M. Dixon, now a U.S. senator from Montana, submitted an amendment to the Army appropriations bill providing for $1,200 for restoration of the soldiers' monument and construction of a suitable iron or steel fence to go around it and protect it from vandalism. [27] Presumably the fence pictured in later photographs (and since removed) was built at this time. [28]

In the meantime, the Forest Service decided to protect the battlefield by withdrawing the area as an administrative site. Forest Ranger W. H. Utley prepared a report and plat on the "Gibbons Battlefield Administrative Site" in the summer of 1909. [29] Forest Supervisor C. K. Wyman approved the withdrawal on September 17, 1909. It encompassed 115 acres in three adjoining rectangular blocks along the foot of the mountain. It included the soldiers' monument together with a suitable area for a ranger station about 400 feet up the draw. Assistant Forest Ranger Arthur M. Keas, who would occupy the site beginning in 1912, described it as "the best location obtainable in this district for the Ranger's headquarters and for fire protection." [30]

Establishment of Big Hole Battlefield National Monument

The final action leading to the proclamation of Big Hole Battlefield National Monument by executive order on June 23, 1910 was mundane. One can search in vain for any profound statements about the purposes of the national monument. Instead, it appears to have begun with a telephone call from a clerk in the GLO to Secretary of the Interior Richard A. Ballinger, relaying citizens' concern in Beaverhead County that the four sections of land mentioned in the unsuccessful national park bill of 1906 were still withdrawn from entry. Should these four sections be reopened to settlement? Secretary Ballinger drafted a memorandum on Big Hole battlefield for the War Department, providing a brief history of administrative developments since 1882 and inquiring whether the lands temporarily withdrawn should be set aside by executive order as a "military reservation." This memorandum was circulated to the Adjutant General's Office, the Quartermaster General's Office, and Army Headquarters Department of Dakota, collecting nine endorsements before returning to Secretary of War Jacob M. Dickinson. Two endorsements were significant. Quartermaster General J. B. Alshire stated – with deliberate vagueness it would appear – that the battlefield had "no marked grave sites now, and according to the best information obtainable it seems that all these bodies have since been removed." Noting the placement of the soldiers' monument, he advised that all that was necessary was to have "sufficient ground set apart for the protection of this monument." [31] Brig. General C. L. Hodges recommended "that a square of five acres be set aside by Executive Order as a military reservation for the better protection of this battle monument," with the soldiers' monument at the center of the square. [32]

Secretary Dickinson approved the proposal for a small reservation to protect the soldiers' monument. Commissioner of the General Land Office Fred H. Dennett confirmed the location of the site and provided information that it did not overlap the single patented desert land claim in the area belonging to one W. H. Reinken. Both Dickinson and Dennett quoted Alshire's statement that there were no known soldiers' remains at the site. Dennett then drafted an executive order, which President William H. Taft signed on June 23, 1910 (Appendix A). The executive order established a five-acre reservation of unsurveyed land "embracing the Big Hole Battlefield Monument in Beaverhead County."

Changes in the Landscape

At the same time that Big Hole National Monument was being established, the Big Hole Valley was undergoing significant change. Montana's homestead boom reached a climax in the first two decades of the twentieth century. While the high plains of central and eastern Montana absorbed the greatest number of hopeful new settlers, the Big Hole and other mountain valleys in western Montana continued to attract more people too. A number of families established ranches along the North Fork of the Big Hole around the turn of the century. These included George Thompson, Johnny Cottrell, Herman Mussigbrod, Don Alby, Weldon Else, and the Lawrence and Bacon families. According to local tradition, the George Mudd Ranch, located in the northwest section of the Big Hole, hosted Theodore Roosevelt during a hunting trip sometime in the early 1890s. [33]

The Big Hole settlers made a living raising cattle and hay. Most of the land entries in the vicinity of the battlefield were made under the Desert Land Act of 1877, which authorized individuals to claim up to 640 acres at $.25 per acre provided that the land was irrigated within three years. Settlers often formed irrigation companies for mutual assistance in developing ditch systems and establishing their land claims. One such company, the Trail Creek Water Company, was incorporated on March 3, 1910. Initial directors of the company were Robert H. Jones, Edward A. Sweet, William J. Tope, John B. Tope, and Hans Johnson, all of Wisdom, Montana. [34] Major developments by this company near the battlefield – and the water rights associated with it – are described in detail in Chapter Seven.

Early settlers had already built a number of small irrigation ditches near the battlefield by 1910. A ditch diverting water from Trail Creek (now the North Fork of the Big Hole) just east of the present Big Hole National Battlefield boundary was depicted on a GLO plat of 1900. It ran northwest to the open meadow, suggesting early hay production in the immediate vicinity of the battlefield. By 1915, when T2N, R17W was finally surveyed, the land along Ruby Creek, Trail Creek, and the Big Hole River was riddled with ditches. [35]

Today, the Ruby Ditch remains the most discernable ditch construction within the national monument boundaries. Although documentary evidence is scarce, this ditch and an associated wood flume and trestle are thought to have been constructed prior to 1900 by the Salt Lake Placer Company. These works carried water from Trail Creek to the benchlands above the valley, where the water was used in a hydraulic mining operation. The resulting gash in the hillside, still visible today, is commonly referred to as the "Mormon diggings." [36] Two other ditches parallel the Ruby Ditch on the slope between the present-day visitor center and the battlefield area.

From 1877 to 1910, the War Department was more instrumental than any other government agency in preserving and memorializing the battlefield. Although the Forest Service acquired a presence in the area after 1906, War Department administration shaped the national monument to 1910. The small area set aside by executive order in 1910 was befitting a war memorial but it was not conducive to historical interpretation. This early site protection laid the foundations for Big Hole National Battlefield's subsequent administrative history. From 1910 to the present, an overriding concern for managers of the area would be to acquire a larger land base that would include more of the battlefield and enable a more comprehensive and balanced view of the battle.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

adhi/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 22-Feb-2000