|

Big Bend

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 6:

Keeping the Faith: The Struggle to Sustain Momentum for Big Bend National Park, 1938 (continued)

Yet another issue on the minds of Maier and Morelock in the spring of 1938 was the impact on the future park of the National Geographic Society boat trip through its canyons. When Maier returned to Santa Fe, he met with Fredrick Simpich to gauge his sentiments on the Big Bend, and on the potential for a major story in National Geographic Magazine. Maier realized that the NPS had erred in not including Morelock and other local sponsors of the park movement in Simpich's visit. "You can understand," said the regional official, "that one of the problems of a party like this is to be able to go where they want to, or where they have previously planned to go, and hence to avoid the general limelight." Maier also noted that "the National Geographic party was not ours but was their own undertaking." The NPS representative, Ross Maxwell, joined the group "solely by invitation," and Maier had offered the services of Everett Townsend "so that proper local arrangements along the River could be effected." Despite these restrictions, Maier expressed satisfaction at Simpich's assessment of the trip. The latter was "most happy over his experiences in the Big Bend," said Maier, "and he feels that this is by all means the high light of his entire Rio Grande trip." Simpich then told Maier "that he is thinking seriously of handling the Big Bend episode as a separate feature story." Such good publicity would aid the land-acquisition program immensely, but Maier cautioned Morelock: "I do not think . . . that [Simpich] would want to be quoted on this statement at this time." [28]

To accelerate formation of the statewide committee, and perhaps to guide its work, the Star Telegram and other Texas newspapers printed stories about the Big Bend country throughout the spring and summer of 1938. The Wichita Falls Times carried news of the state convention of the Daughters of the American Revolution (in the 1930s a powerful women's organization nationwide). Held in Fort Worth, the DAR gathering called for support of the Big Bend fundraising, along with its more-typical initiatives in scholarships and promotion of patriotism and citizenship in the public schools. The Star Telegram itself continued to identify donors to the land-acquisition fund, with the April 10 issue praising the "Sul Ross Concho Valley Club" of San Angelo for its contribution of five dollars. The Fort Worth paper also ran a feature by Alpheus Harral, a high school student in Fort Stockton, entitled "Terlingua, Largest City in Big Bend Park, Busy Place." Harral had visited the mining town of some 600 people, whom he described as "mostly Mexicans," to learn more about the area to become Texas's first national park. "Terlingua has one of the largest mines in the country," said Harral, "and most of the people in and around the town work in the mine." Harral happened to be in Terlingua on a Sunday, where he witnessed not a surge of miners headed to work, but instead a parade of "Mexicans and a few Americans [leaving] their little, flat topped adobe houses, dressed in their Sunday best, including shoes, to get to the town church." The Fort Stockton youth then noticed that "a Catholic priest preaches to them for two hours." Upon leaving the service, community members went home for lunch, followed by a ritual where "the older people stay home the rest of the day, but the young lovers will take a ride in a Model ‘T' or go walking." Visitors curious about life in the Big Bend country, said Harral, found most intriguing the local gas station, which the Fort Stockton youth described as "a combination of a mining headquarters, postoffice and general store, and it is about the only filling station in the Big Bend." Tourists contributed to the bustling scene witnessed by Harral, joining with miners and their families to patronize the local merchants. At sunset the visitors departed, and Harrel described Terlingua returning to the quiet that marked its existence most of the week: "The light man replaces the gas lamps, cleaned and ready to light the dark streets. Then the sun disappears over a range of mountains, and a busy Sunday has ended." [29]

Where Alpheus Harral spoke as a wide-eyed youth about the distinctive cultural dimensions of the future national park, Dean Carpenter, manager of the Hotel Paso del Norte in the city of El Paso, provided the tourism industry with a glimpse of the potential for visitation to the Big Bend country when he led a party of prominent west Texas businessmen on a raft trip through the Rio Grande canyons. Carpenter, interviewed in the May 1938 issue of the Texas Hotel Review, spoke of the "exploitation of the wealth of possibilities for state tourist travel increase offered by the federal park project in the Big Bend Country." Lured by rumors that the park service would "spend $6,000,000 developing this great scenic region," Carpenter took a group that included Dick Cochran of the White Motor Company of Denver; Dr. Benjamin F. Berkeley of Alpine; Dale Resler, a tour bus operator from Carlsbad, New Mexico; L.A. Wilson of the El Paso chamber of commerce; C.M. Harvey, president of the El Paso National Bank; and H.F. Greggerson, Sr., chief of the El Paso County farm bureau. Carpenter's group had spent their first night at the Chisos CCC camp, which he described as "the proposed location for the central hotel and resort planned to be similar to the hotels in Yellowstone and other familiar projects." The party also noted that "seven miles south of this camp there is easily accessible by a one-day horseback ride a point from which the Rio Grande River can be seen meandering for seventy-five miles." Echoing the sense of wonder of Walter Prescott Webb, Carpenter told the hotel trade journal: "‘It is impossible to give an intelligent description of this area.'" Yet "‘as it becomes more familiar to the public,'" said the El Paso hotelier, "‘it will be known as a wonder of nature rivaling Yellowstone, Yosemite or the Grand Canyon.'" [30]

The burst of promotional literature and feature stories on Big Bend coincided with Governor Allred's formation of the fundraising committee, which met on May 23 in the Texas state capital. NPS director Arno Cammerer sent Herbert Maier to represent the interests of the park service, and the latter reported that the organization took seriously Allred's charge to collect up to $1 million dollars as quickly as possible. "The general meeting," said Maier, "started with the Governor's statement that the Secretary [of the Interior] has advised him on several occasions that this project is very close to his heart." Then Amon Carter, "who is regarded as the outstanding citizen of Texas, and who is widely traveled, followed with a talk in which he discussed the value of the tourist industry to the state." Maier himself addressed the 100-plus member committee "with an outline of the history and policies of the National Park Service." Then the group nominated Allred as "honorary president," Carter as its chairman, and Morelock as vice chairman. Other luminaries among the 26 members of the executive committee were Star Telegram editor James Record, Jesse Jones of Houston (director in the 1930s of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation [RFC], and in World War II the director of the RFC's Defense Plant Corporation [DPC]), Wendell Mayes of the state parks board, Mrs. Richard Turrentine of Denton (president of the Texas Federation of Women's Clubs), James Casner of Alpine, and Houston Harte of San Angelo (editor of that community's newspaper, the Standard, and a future landowner in south Brewster County whose donation of land in 1980 triggered much debate over expansion of the park boundaries). [31]

Moving quickly on Allred's request, committee members pledged $25,000 of their own money for "publicity and motion pictures." The group then decided to establish a goal of $1.5 million, with two-thirds of that "public subscription to buy the private holdings," and "the half-million to be secured by a state legislative act to reimburse the Permanent School Fund for its holdings." Among the suggestions of high-profile donations were "to have each school child in the State contribute a dime for eight consecutive weeks." Maier informed Cammerer that "the plans advanced seem, for the most part, practical." He believed that "when a really substantial sum is at hand it is felt no difficulty will then be experienced in putting through the legislative act authorizing the State to reimburse the School Fund . . . as this will largely amount to a transfer on the books." Unfortunately, cautioned Maier, "the stumbling block . . . is still the matter of the mineral rights held by the School Fund." Carter's committee realized that NPS policy prohibited land donations without cession of mineral rights. Yet "they feel," said Maier, "that the fundraising campaign should not be complicated and the enthusiasm dampened by emphasizing this controversial question too much at this time." Their solution, then, "would leave with the School Fund the right to its royalties, but would place in the [Interior] Secretary's hands the decision as to whether mineral deposits, were they later found to exist, would be developed." Maier noted also that "it could be further agreed that such development could only take place in time of a national crisis." [32]

Maier then speculated that "if a really considerable sum is raised by next fall, it is expected that Governor Allred will bring up the bill to reimburse the School Fund for its land at a call session, since such a session appears likely in any case." Given the time needed to collect the million dollars ("three years at best," said Maier), the committee wanted "purchase [to] start immediately and not await collection of the entire fund," with "such owners as make the best offers" being the first contacted. These actions, concluded Maier, represented the most hopeful sign of success that the NPS official had seen in several years. "Considering the circumstances under which the meeting was called," he told Cammerer, "the strength of the personnel comprising the new Executive Committee and the enthusiasm displayed, I feel we can assume that the project is now very definitely on its feet." [33]

No sooner had word reached Alpine of the fundraising committee's plans than did local sponsors initiate their own aggressive publicity campaign, to the chagrin of Herbert Maier. As with the announcement in 1935 of congressional authorization, the NPS had to remain officially neutral on park promotion efforts. Yet Maier wrote to Leo McClatchy one week after the Austin meeting: "I know that the Alpine group is not cognizant of the fact that so much of the fine publicity on the Big Bend, which is getting into the Texas newspapers and eastern newspapers actually comes directly, or indirectly from this office [Santa Fe]." Maier recalled how, "at the meeting in Austin the other day, Gov. Allred held up a big spread from one of the New York papers that I know had its origin in this office." He then told McClatchy: "It seems to me that we should let the Alpine people know what we are doing, and since we want to send our clippings to the Washington office that it may be well for you to keep track of all articles that appear to come directly or indirectly from us." Then McClatchy could "send a letter to Dr. Morelock at the end of each month simply listing the dates and newspapers in which the articles appeared." Maier also cautioned that "of course we do not want to make a mistake in any case where the dope has originated from Alpine." He was motivated by the sense that the local sponsors "naturally assume that they have been the fountainhead of this publicity." Yet Maier also realized that "it may be that we should let the matter rest as it is but if you can think of some method, please let me know." [34]

By mid-summer, the fundraising campaign had spread across Texas, energizing local champions of the park like Everett Townsend. Writing to Maier on July 3, he noted that Brewster County envisioned a new road from Alpine to the park site; a sure sign that the planning stages had already begun. Townsend also wrote that Amon Carter's committee had received their state charter, to operate for five years "with no capital stock, but with an estimated $25,000 in assets." Then Townsend spoke of efforts by Carter and the committee to solicit funds from the John D. Rockefeller Foundation, better known for their support of educational and health programs in impoverished communities in the South (and a critical donor to the private fundraising for Great Smoky Mountain National Park). "Something may be had there after we ‘do our do,'" said Townsend, "but in my opinion Rockefeller will expect us to ride our horse about as far as he will go before he comes to the rescue with a fresh mount." Maier acknowledged Townsend's advice, and held a meeting in Washington with Representative Thomason and NPS director Cammerer regarding the school-lands controversy. These federal officials agreed that "the best way to handle the matter of the [Interior] Department's position on the Big Bend school lands and mineral rights would be for the [Carter] Committee to draft the bill to be submitted to the State Legislature and to send a copy to the Secretary." Maier then informed Townsend that Thomason "felt very strongly that the bill should not be presented in a called session but should be introduced in the regular session next January [1939]." Both Thomason and Maier believed that "this will give the Committee an opportunity to raise a substantial sum in the meantime by private subscription and which will have its effect on the [Texas] legislature." Cammerer concurred in the thinking of Maier and Thomason, expressing most concern about the school-lands issue. Since "surveys by Federal, State and private geologists have at present discounted the presence of any paying quantities of minerals in the area," said Cammerer, "it might be possible for us to consider such a provision [waiving mineral rights to the school lands]." The NPS director recalled that "experience has shown that after ten or fifteen years the need for such provision would not be pressed as of further importance." Then "the Texans who are not as yet educated to the full meaning of a national park," said Cammerer, "would be the last at that time to desire exploitation of that park." [35]

Within 30 days of the Washington meeting of Maier, Cammerer and Thomason, events in Texas changed the future of Big Bend National Park in ways that even the most optimistic park sponsor could barely ascertain. Voters in the Lone Star state went to the polls that August to cast their ballots for the Republican and Democratic candidates for governor, with W. Lee "Pappy" O'Daniel winning the latter primary. As Texas remained a "one-party" state (no Republican had won the general election for governor in the twentieth century), O'Daniel would become the new target for promoters of Big Bend to cultivate. Within one week of his primary victory, O'Daniel announced his intention to support state funding for Big Bend National Park. "You may well imagine my pleasure in seeing this," Townsend wrote to the future Texas chief executive, "because I have for years given much of my time and as liberally as possible of my means to this project which means so much to our beloved State and perhaps more to the American Continent at large if we succeed in making it an International feature as many of us hope to do." Townsend recounted for O'Daniel how "for 44 years I have lived in or adjacent to the Park region." While in the 43rd legislature, Townsend "fathered the first bills to make of it a State Park, and immediately began a campaign to bring it to the attention of the National Park Service." Townsend also "assisted in writing the first report made by the National Park Service to the Secretary of the Interior, which recommended and set out its importance as a National and International project." This report in turn "brought about the Congressional action authorizing its creation as a National Park." Townsend let O'Daniel know that "I am thoroughly familiar with the whole region, and have accompanied the National and International Park Commissions on all trips of inspection through the area on both sides of the Rio Grande." [36]

Beyond his work in west Texas to make Big Bend National Park a reality, Townsend reminded the next Lone Star governor that "I was in Austin during the whole of the last regular session [1937] of the Legislature, much of the time on my own expense." While there, Townsend "did [his] bit toward the passage of the appropriation for the purchase of the lands which my good friend Governor Allred afterward vetoed." Townsend also wanted O'Daniel to know that "I have made a thorough study of the records of all lands and have checked the ownership of every tract involved." From this Townsend concluded: "I believe that I am fully familiar with every technical question that may arise when the time comes for the writing of the legislation to transfer the lands to the National Government." In order for O'Daniel to acquaint himself with Townsend, and with Big Bend, the former county sheriff asked: "Can you not find the time to visit the Park region sometime this fall?" Townsend could assure O'Daniel that "the citizens of Alpine and Brewster County would be most happy to see you." He listed the many state and NPS officials who had expressed to Townsend their support for the park project, among them James Allred, Walter Woodull, Coke Stevenson, and Herbert Maier, and promised "my support for the success of your coming administration." [37]

As the 1939 legislative session neared, and Governor O'Daniel considered measures to fulfill his promise on Big Bend, the NPS and the Interior department heightened public curiosity and encouraged potential donations. Harold Ickes took the occasion of a dedication ceremony for the Dr. Edmund A. Babler State Memorial Park near St. Louis, Missouri, to call for a similar federal park unit at Big Bend. "Establishment of the proposed Big Bend National Park," said Ickes, "will remove the thought in the minds of many that the Mid-Continent has nothing worth while to offer in scenery." The Fort Worth Star Telegram reported that the audience in St. Louis, which was joined by a "national radio hookup," learned that land for the 1,600-acre Babler state park came from the family, as well as an endowment of $1.5 million for its maintenance. Seeing a trend of private support for public parks, Ickes called upon his audience to sponsor park creation initiatives for Big Bend, the Florida Everglades, the California Redwoods, and "the Alaskan Bear Sanctuary." "If [Big Bend] national park becomes a reality," said Ickes, "we will stop the ruinous erosion now going on due to overgrazing by sheep and goats that are trying to live where cattle and horses starved." In so doing, "we will turn the mountainsides and the badlands and the grassless plains back to the antelope and the deer and the bears and the panthers and foxes that lived and thrived there before the white man brought what he calls civilization." Ickes characterized the Big Bend as "a wilderness now, a poverty-stricken wilderness, but nature will restore its richness if given a chance." He then intimated that the noble efforts to raise funds for Big Bend stood in jeopardy. "Private individuals must come forward," said the Interior secretary, "unless the Governor [James Allred] relents, for no federal funds can be used for land acquisition." Yet Ickes had faith that Big Bend, along with the other endangered park sites, could be protected for the enjoyment of the American people. [38]

Harold Ickes' nationally broadcast plea for Big Bend gave park sponsors a new angle of promotion, one that the Fort Worth Star Telegram, and Amon Carter's fundraising committee were quick to exploit. Carter's newspaper told its readers on October 17 that "Texans are appreciative of the nationwide publicity which Secretary Ickes gave to the proposed Big Bend National Park." The Star Telegram, ever conscious of the economic boon such a facility would mean to the Lone Star state, declared that "it is logical to assume that many tourists will as a result [of the speech] be attracted to Texas." Yet the most important audience for Ickes's words, said the paper, were "Texans who on vacation think they can find enjoyment only by going to Colorado, Yellowstone National Park and other distant places to see majestic mountains, deep canyons and other beauties of nature extravagantly expressed." "Too many Texas people," argued the Star Telegram, "are unaware of the rich potential asset which they have in the Big Bend territory and therefore are indifferent to the development of a national park there." The Fort Worth paper warned its readers that "after all, the success of the project depends upon the number of converts to it in the State who become salesmen and contributors to the Big Bend fund." Ickes's words, the Star Telegram concluded, "should spur Texas people on to carry out their part of the project." [39]

So that Ickes's mandate could be achieved, the fundraising committee met in early October to plan its activities. Herbert Maier attended the session at which the members voted to employ Adrian Wychgel of New York City as manager of the campaign. "Mr. Wychgel, I understand," Maier told Cammerer, "is connected with the firm that handled the raising of funds for the Shenandoah National Park." The Big Bend committee wanted Wychgel "to raise $50,000 to finance the campaign proper from which sum must also come his fee." Maier did note that "Mr. Wychgel is working closely with a Mr. Sculley of Austin who has done considerable fund-raising in Texas in the past." Both individuals, according to Maier, "are attempting to raise the first $50,000 through subscriptions from wealthy men and firms, such as large oil companies, in Houston, San Antonio and other large Texas cities." Unfortunately, said Maier: "To date they have had only limited results." Amon Carter, however, told the committee that "if Mr. Wychgel is successful in raising the first $50,000 to finance the campaign, he will then undertake the job of raising the whole fund." Horace Morelock and the Alpine boosters, said Maier, "are watching the thing closely." Should Wychgel fail, "it has been suggested that they [the west Texas sponsors] attempt to obtain the initial $50,000 appropriation at the next session of the Legislature, which should not be difficult." Maier did caution Cammerer: "On account of the above uncertainties and the coming state election, it has not yet been determined what other legislation the [fundraising] Committee will introduce for clearing up the land situation." The Santa Fe official recalled that "some $25,000 to $50,000 was earlier raised by popular subscription but this money can only be used for the purchase of land." Thus Maier concluded somberly: "At present I believe there is nothing we can do but await the results of Mr. Wychgel's efforts to raise the first $50,000." [40]

Once the Wychgel contract became public, Horace Morelock followed up on Everett Townsend's invitation to W. Lee O'Daniel to visit Big Bend. The odds-on favorite in the Texas governor's race had planned a tour of west Texas in the last days of October, and Morelock hoped that he could devote time to seeing the wonders of Big Bend and Brewster County. Carr P. Collins, an official with the Fidelity Union Life Insurance Company of Dallas, and the organizer of O'Daniel's west Texas itinerary, offered Morelock an apology for not including Sul Ross and the dedication of U.S. Highway 90 while in the area. Big Bend sponsors had learned that O'Daniel planned a quick stop on his way east from El Paso to see McKittrick Canyon, a part of the future Guadalupe Mountains National Park adjoining New Mexico's Carlsbad Caverns National Park. "Personally," said Collins, "I think the entire time [one day] devoted to an inspection of the Big Bend Park site is of more importance." Collins knew that "when a prominent man visits a certain section of the country, the people want him to see everything that is there to be seen." Yet if the O'Daniel party tried "to visit your College, it will take so much time out that we could not inspect the Big Bend Park site." Instead, Collins advised Morelock: "We are counting on you to meet us in El Paso and make the trip back to Alpine that night, via McKittrick Canyon." [41]

Soon after the "official" gubernatorial election of O'Daniel in November 1938 to succeed James Allred, Morelock and the west Texas park promoters took heart from word that the fundraising campaign neared its commencement. The Sul Ross president told James Record that Colonel William Tuttle of San Antonio had raised some $3,000, while Colonel J.F. Josey of Houston believed that his hometown's share could be raised, and Austin committee members "might get $1,000 . . . if we would go at it right." Yet Morelock also had disturbing news to relay to the editor of the Fort Worth Star Telegram. "I am advised," wrote Morelock, "that considerable trouble has arisen in the past relative to contracts with promoters, which grew out of the fact that the contract did not specifically state that the commission was to be based only upon the cash actually collected and not upon pledges." The Sul Ross president believed that "Mr. Carter is too good a business man to overlook things like this, but I thought it might be well to bring to your attention some experiences along this line which have caused considerable trouble in the past." Morelock, however, did not want to dwell on this issue, as his speech in Austin in October had generated much enthusiasm for Big Bend. "A number of women inquired as to where they might get information on the park campaign," said Morelock, "in order that every Federated [Women's] Club in Texas might give a program on this subject." He hoped that Record could supply him with a bulletin and a movie promoting the park, especially the upcoming address that Morelock and G.P. Smith of Sul Ross would give in Dallas to the Texas State Teachers Association. [42]

Following Morelock's appeal to the Star Telegram for assistance in his round of public appearances on behalf of Big Bend, governor-elect O'Daniel decided to return to the Big Bend country to devote more attention to the future park site. Morelock joined the gathering in the Chisos CCC camp on November 15, where he heard Herbert Maier outline the NPS's plans. "I do not know what your reaction was to the Governor's thinking relative to a national park," Morelock told Maier, "but I am feeling happy over what he, the lieutenant governor, and the speaker of the house, etc., had to say on this subject." Morelock himself discussed with O'Daniel "the three-volume edition on the national and state parks which was recently issued by your department." He then recommended that Maier send copies to O'Daniel, Coke Stevenson, and Emmett Morris of Houston. Morelock had seen a copy of the multi-volume NPS study when he had met with Amon Carter, which led him to think that "the leading newspapers of Texas should also have a copy, in order that they may boost the park campaign, once it is well under way." [43]

Another long-time champion of Big Bend, Everett Townsend, could not accompany the O'Daniel party in the Chisos that week, as his wife's deteriorating health had required her to seek treatment at Eureka Hot Springs, Arkansas. Yet Townsend was flattered to receive Maier's invitation, and his kind words about the role that Townsend had played in keeping the Big Bend project alive. Then Townsend advised Maier of problems developing in the park area among landowners displeased with their new neighbor. "As already intimated in other letters," said Townsend, "I have been somewhat disgusted at the capers of some of my friends and largely because of my other troubles, may have been somewhat discouraged with the progress made by our State Committee." Yet he declared himself "still in the ring and ready to go as far as anyone in putting over our Project." Townsend also had entered into discussions with state parks board director William Lawson about "creating a job for me to look after the care of the geological and other valuable areas in the Big Bend to the end of protecting them from American vandals." Townsend believed that "we can have the co-operation of all the large non-resident land holders for that purpose, as well as the local ranchmen." Lawson and he had pursued this option because "for the State to do it there would have to be a special law passed and an appropriation provided;" a circumstance that could be avoided if the park service would fund the caretaker position that Townsend envisioned for the Chisos property. [44]

Herbert Maier then weighed in with his assessment of the status of Big Bend's future, as filtered through his conversations with governor-elect O'Daniel and his party. Among the issues discussed between Maier and O'Daniel was the fundraising campaign. "The Executive Committee," Maier wrote to Cammerer, "has now pledged itself to raise $25,000 for initial publicity work, and $15,500.00 has been paid in . . . cash with the remainder definitely pledged." Once this money was available, the committee would hire its fundraiser and rent space in Austin for the work. "It is estimated the campaign is to last two weeks," said Maier, "although this seems very brief to me." The committee would pay $10,000 to the fundraising firm, and "a representative of Adrian Wychgel and Associates of New York City has been out here and has returned to New York." Maier cautioned that "I do not know definitely to what extent he was impressed with the chances of raising the money" when the initiative began in the spring. Maier also did not have a good sense of what lengths Governor O'Daniel would go on behalf of a Big Bend appropriation. "He is in for some pretty tough sailing," Maier informed the NPS director, "what with his pledge on Old Age Pensions, etc." Yet Maier took comfort in the fact that the governor's "personal aid is State Senator Coke Stevenson, who has always been the principal leader in Big Bend legislation." Stevenson had been elected lieutenant governor that month, and Maier concluded that there "need be no fear from the new Governor." [45]

What Maier had learned about the upcoming legislative session was that "the fund-raising committee will have nothing to do with legislation." This instead would be the "province of the West Texas group." They "tentatively planned to ask the legislature for $750,000.00 (which is the amount it passed two years ago) with the condition that the private subscriptions match this dollar for dollar, or something to that effect." An alternative idea, said Maier, was that "the campaign will be put on first, and a bill introduced for any unraised portion." As to "the problem of school lands, mineral rights, etc," Maier reported that these "should not be brought up until after the money is at hand." What he called "these difficult matters" would "more readily solve themselves with the aid of public opinion, although it is likely they will force their way into any bill proposed for an appropriation." Then Maier expressed some caution about the reputation of the fundraising body itself. "While Chairman Amon Carter is one of the most influential men in the State," said the acting director of Region III, "there are those on his committee who are holding back because they feel he is an opportunist, and will reap all the credit in the end." Maier also had heard "other rumblings -- but this is normal to a large promotion of this sort." He believed that the park initiative "is now in ‘big' hands in the State and we can expect definite action next Spring," even though Maier had to concede to Cammerer: "Since Governor O'Daniel has not yet taken office, things will probably continue in a nebulous state until after the first of the year." [46]

To fill that vacuum in Austin, the NPS and Horace Morelock redoubled their efforts in the last weeks of 1938 to saturate the news media with stories about the Big Bend fundraising venue. Herbert Maier spoke in Fort Worth just before Thanksgiving on the future park, and of the gift that Texans could give themselves by purchasing the lands in Brewster County needed for its inclusion in the NPS system. The Star Telegram quoted Maier as suggesting that Big Bend would be one of the last parks created by Congress, the other two being the Everglades and the Kings River Canyon in California's Sierra Nevada. "The three areas now desired," reported the Star Telegram, "will complete the national system as now planned, [Maier said], expressing the hope that Texas would not pass up its opportunity to be included in that system." The international dimensions of Big Bend also received praise from the acting Region III director: "‘I believe it is a social opportunity that will be copied all over the world.'" The Star Telegram cited Maier's many visits to the future park, calling him "probably . . . more familiar with the Big Bend area than any other man in the country." Maier promised that federal funds would flow immediately upon Texas's purchase of the park lands, bringing to west Texas "lodges and other facilities to accommodate every income class, and highways and trails to the various points of interest." "‘Texas can get all the federal money needed for development of the park,'" Maier told the Star Telegram, which quoted the NPS official as "mentioning the size of the State's membership in Congress" as proof of the wisdom of the private fundraising initiative. [47]

Maier's assertion that the nation would soon have no more areas worthy of NPS preservation struck a nerve among his superiors in Washington, in that they worried about negative public reaction (which in turn could affect fundraising for Big Bend). Thus Conrad

Wirth inquired of Maier: "I doubt that the newspaper quoted you correctly, since, as you know, there are a number of national park projects on which the Service is now working and there will undoubtedly be more." Wirth advised Maier to "clarify the record" on Big Bend, which the acting director of Region III did by contacting Robert Hicks of the Star Telegram. Hicks had returned to Fort Worth in early December after a visit to Big Bend, and his series of stories prompted Maier to praise "how you could absorb so much of the technical knowledge concerning the project as thoroughly as you did." Maier considered "the articles you wrote" to be "a great help to the campaign for consummating this project as a great international park." His only concern was Hicks's reiteration of Maier's statement that "the two or three outstanding areas which I named are the only areas in which the National Park Service is still interested." Maier apologized to Hicks for the error, stating that "there are several other wilderness areas of national park calibre throughout the country, in Alaska and our Island possessions, which . . . are quite likely to qualify for national park status." Hicks also had gained the impression that Big Bend would be the NPS's only all-year park; an understandable belief since the majority of the park service's 23 units were located at high altitude. "Most of our major national parks," wrote Maier to Hicks, "are closed during the winter period but such parks in the South as Grand Canyon and Carlsbad Caverns, and we hope later the Big Bend, are all-year-round parks." [48]

Repercussions from Maier's lapse in judgment did not cease with an apology to a Fort Worth reporter. NPS director Cammerer asked the acting Region III director to reveal the source of his information about Big Bend as one of the last desirable places for a national park. "It is unfortunate," said Maier, "that I was misquoted and I felt very chagrinned when I read the article a few days after I had given the talk." The Star Telegram's Robert Hicks, said Maier, "is a friend of mine, and I have corrected him on the facts so that if he has occasion to write again on the subject of the Big Bend he will not repeat the statements." Maier acknowledged correspondence with Governor-elect O'Daniel "as to what other areas the government is attempting to acquire at this time." Maier "named some of these but did not state that they were the only remaining areas desired." He then was "further misquoted by the same reporter as saying that no mineral deposits are ever found in igneous formations and that the Big Bend will be the only National Park that will be open the year round." All Maier could surmise was that "Hicks, apparently, wanted to make a good story." [49]

While Maier emphasized the imperative of Big Bend for Texas donors large and small, Horace Morelock asked Amon Carter for advice on publicizing the May 1939 meeting of the West Texas Chamber of Commerce meeting (the group most involved in subsidizing park promotion). That organization hoped that Carter could prevail upon Harold Ickes to deliver their keynote address. Herbert Maier in turn solicited Morelock for "any information regarding any legislation which it is planned to introduce for the coming session in connection with the Big Bend." James Record had advised Maier that "as regards asking the State for funds it may depend somewhat on the amount that can be collected in the campaign." A gap between the spring fundraising effort, and the winter session of the state legislature, threatened any such legislation for the 1939 session. Maier also needed to know Morelock's sense of "any bill that may be introduced reimbursing the State School Fund for its land holdings or its mineral rights." Then Maier confided that the park service faced a dilemma regarding the Guadalupe Mountain area known as McKittrick Canyon. Governor-elect O'Daniel had included this area in his post-election tour of west Texas because Culberson County Judge J.C. Hunter had offered the Texas State Parks Board between two and three thousand acres for a state park. Maier himself had surveyed the entire Guadalupe Mountain area in April 1938 on behalf of the park service. Judith K. Fabry contended in Guadalupe Mountains National Park: An Administrative History (1988), that Maier's report found that "except for the southern extremity of the range, the mountains provided little in the way of scenic or wildlife values." Now Maier contemplated Judge Hunter's offer, which the acting Region III director preferred go to the state parks board "for summer cabin sites and thereby a permanent summer population would be at hand to make use of this State Park which otherwise would be quite severely isolated." If the NPS followed his suggestion, said Maier, "this would be far better than to attempt to raise $246,000 from the State for purchase of the entire [McKittrick] canyon area." Maier had discussed this with Wendell Mayes of the state parks board, and "apparently the State Board's policy will be to accept the donation of the smaller area from Judge Hunter and to not favor a bill for purchase of the entire area which bill would interfere with a Big Bend bill." [50]

The NPS office in Washington, cognizant of the need for a partnership with the new Texas governor in any land-acquisition initiatives, made sure to compliment O'Daniel on his victory, and promise cooperation in his tenure as Texas's chief executive. Acting NPS director Albert E. Demaray told O'Daniel that "the Big Bend country is, of course, one of our truly unspoiled areas, ideally suited for national park purposes." Thus "it devolves on the State and Nation," said Demaray, "as I see it, to carry the project through as expeditiously as possible." The NPS saw Big Bend as "a socially and economically sound park proposition, which will pay for itself over and over again under the land use policies followed by this Service." Demaray thanked O'Daniel for "your interest in the project as reported to me by Mr. Maier," and he spoke of "looking forward with a great deal of pleasure to making your acquaintance when next it is my good fortune to be in Texas." [51]

By year's end, park service officials and private interests championing Big Bend National Park cast their gaze upon the Texas state capital in Austin. Key legislators received letters like that of Amon Carter to state senator H.L. Winfield of Fort Stockton. Carter informed Winfield: "It was the opinion of the [fundraising] Committee at its organization meeting in Austin that we should not seek a legislative appropriation for the Park at this time." Instead the group believed that "we should take our plans before the people of Texas and of other states, perhaps, to get the necessary funds." Carter made clear the committee's determination to obtain private monies wherever possible by declaring: "In fact, any effort to secure a legislative appropriation will interfere with our plans." What the fundraisers needed from Winfield and his colleagues was "a land bill covering the two points-namely, school lands and mineral rights - and that before same is offered, the National Park Service see the bill." Carter believed that "such a course will mean that this time we won't have to get any remedial amendments or make any changes before the final transfer of the land is made." To aid Winfield in his deliberations, Carter included a chart on the "Land Status" at Big Bend. As of the end of 1938, the state parks board could claim ownership of the surface and mineral rights of 13,460 acres (or a mere two percent of the 788,682 acres defined by Congress in the 1935 legislation authorizing creation of Big Bend National Park). The state school fund held 475,461 acres, with some 132,107 of those acres deeded to the parks board (but with the mineral rights still accruing to the school fund). When Carter added the 299,761 acres of privately owned and patented lands, the scale of property acquisition for Texas's first national park became quite clear to Senator Winfield and his fellow legislators. [52]

The year 1938 had tested the park service and the west Texas sponsors of Big Bend in a myriad of ways. Much time and energy went into plans for a statewide fundraising campaign, the likes of which the Lone Star state had never seen. Yet Everett Townsend, Horace Morelock, Herbert Maier, and other federal and local officials rarely tired of the challenge to bring Big Bend into the national park system. Its beauty and grandeur, coupled with the desperate straits in which most landowners found themselves (even five years into the New Deal), suggested that a new political administration in Austin might adopt Big Bend as the Lone Star state's first effort to preserve nature's beneficence in partnership with the NPS. When that moment came, the dark days of 1938 would be instructive, as few public officials came to the Big Bend to dream of a national park, and fewer visitors could imagine how the landscape would appear once protected by the policies and regulations of the National Park Service.

| |

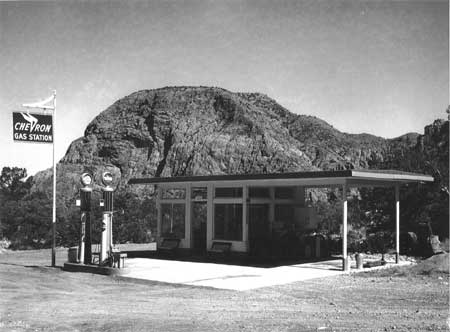

| Figure 11: Chisos Basin Service Station (c. 1950) | |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

http://www.nps.gov/bibe/adhi/adhi6b.htm

Last Updated: 03-Mar-2003