|

Big Bend

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 12:

Redrawing the Boundaries of Science: 1937-1944 (continued)

With the official opening of Big Bend National Park in the summer of 1944, the recommendations of Taylor and the ecological survey crew would become part of NPS planning and interpretation. Yet one feature of research work in the Big Bend area that did not occur was the dream of Howard Morelock to link his small teachers' college in Alpine with Big Bend's scientific agenda. While Morelock labored statewide in the late 1930s and early 1940s to raise funds for the purchase of lands in the future national park, he also tried to position Sul Ross State Teachers' College in the flow of scientific research on the Big Bend country and the international park. As early as August 1938, NPS archaeologist Erik Reed had written to Frank M. Setzler of the U.S. National Museum in Washington to recommend the "coordination of all Big Bend archaeological work with Sul Ross as the center." Reed had discussed the idea with archaeologists on staff at the Alpine college, and with Dr. Harry P. Mera, director of the Santa Fe-based Laboratory of Anthropology. Reed's concept was called the "Conference on Big Bend Archaeology," with its goal "to persuade expeditions of other organizations to coordinate their work" with NPS plans for the park. The assistant regional archaeologist wanted to build upon his 1936 reconnaissance of Big Bend, including the excavation of small caves and open sites, and the connection of these pre-contact sites with historic knowledge. This conference also could ensure professional treatment of human and faunal specimens, as per the stipulations of the Antiquities Act. [71]

Reed then outlined the "logical headquarters" for this informal network of academics and NPS technicians: the West Texas Historical and Scientific Society Museum at Sul Ross. The park service archaeologist described the Alpine campus as "fortunately equipped with quite adequate laboratory facilities, storage space, etc., which are at the service of any reputable archaeologist working in the Big Bend area." Reed believed that "to make the museum a still better base of operations," the NPS should encourage institutions and scholars working in the region to adopt "a uniform style of site designation - probably one or another variation of the Gila Pueblo system, such as already used in three of the more extensive site-surveys in the region." Researchers then would "deposit with the said museum copies of all reconnaissance-survey site descriptions." From this "a complete file of Big Bend sites will thus be built up at this logical center, for the use of all qualified investigators." Finally, an NPS-Sul Ross collaboration would address Reed's greatest concern: "Vandalism, curio-hunting, commercial collecting, and well-intentioned but inept field work by unqualified individuals." By having trained archaeologists on campus at Sul Ross, Reed hoped that "activities by unqualified individuals that cannot very well be prevented - as is often the case - shall be assisted and guided into the use of proper methods as far as possible." [72]

Nothing came of Reed's request, so in the fall of 1939 President Morelock approached the park service with a new plan for a "biological service medium" on the Alpine campus. Everett Townsend wrote to regional NPS director Hillory Tolson to promote his ideas, reminding Tolson that "scientists from all parts of the country come to the Big Bend in search of new materials in Science." Townsend noted that "practically all of these scientists come to the College first to get information as to the best places to go." Sul Ross had built what Townsend called a "$75,000 museum" that contained "more than 12,000 specimens," while Dr. Omer Sperry had a contract with the NPS to serve as an "Associate Biologist." Then Townsend claimed that "educators are more and more reaching the conclusion that field work is more important than book work, especially in the field of Science." Sul Ross subscribed to this Progressive idea, and "a lot of valuable materials in Geology, in Botany, in Anthropology, etc., are in this section." Yet another reason for supporting Sul Ross's request was that "the people of the Big Bend, together with the National Park Service, are the ones who kept the Big Bend National Park project a live issue." Townsend reminded Tolson that "some people down state and within some institutions gave little thought and no effort to the importance of a National Park in this section," and "because of imagined mineral values, did everything they could to oppose this at a most critical period." [73]

If the park service could provide the funds, Sul Ross could design a facility that included a lecture hall and laboratory, and lodging for six to ten researchers. Townsend noted that Sul Ross faculty "could take them down, work with them, and together they could achieve better results than they could without some definite equipment and well-worked out plan." The local advocate for the national park added that "It is also important to have a place for representative citizens in promoting the best interests of the National Park and other distinguished visitors." Townsend realized that "perhaps the National Park Service would not be in a position to give to the College a deed of this set-up." Yet he hoped that "a cooperative agreement can be worked out in such a way as to make this Biological Center serve the purposes that I have indicated." Tolson might consider Sul Ross's idea "premature," but Townsend claimed that "other institutions are interested in capitalizing on what the people of this section and the National Park Service have brought to the attention of the public." [74]

Park service officials from Santa Fe to Washington took notice of Townsend's correspondence, given his stature in Brewster County and his work in the Texas state legislature on behalf of the land-acquisition bill. Tolson notified Carl Russell, supervisor of interpretation for the NPS, that "it is believed that you will not desire to encourage or approve Mr. Townsend's proposal as the construction of an educational unit inside of the park area by Sul Ross State Teachers College would, undoubtedly, lead to requests for authority to do so by other institutions." Tolson also hoped that "scientific research and investigation in the Big Bend National Park (when it is established) should be handled by the issuance of permits, in accordance with existing regulations." Victor Cahalane, chief of the wildlife division of the NPS's branch of research and information, also told Russell that "the Service should not commit itself to turning over to the College functions that are the responsibility of our technical divisions." Cahalane did admit, however, that "facilities for scientific workers are lacking." Instead, he suggested that "a simple temporary laboratory and dormitory building be constructed in the Basin as a CCC project." Then the state of Texas and Sul Ross could "be requested to assume temporary custodianship for the benefit of visiting and their own scientists." [75]

Such high-level attention to Townsend's appeal netted the former Brewster County sheriff a personal note from Arthur E. Demaray, associate director of the park service. The agency was "convinced of the importance of field work to both research and education in the natural sciences," wrote Demaray, and concurred that "adequate facilities for field studies in the Big Bend area are very desirable." The associate director then noted that "such facilities are provided in some of the national parks by the park museums." These entities also were "accustomed to cooperate closely with outside institutions and organizations," said Demaray, citing the museum at Yosemite National Park. It housed "a laboratory accommodating thirty students," while "professors from the University of California, Stanford University, and other nearby colleges often bring their classes there for field study." The NPS also had under construction a museum at Ocmulgee National Monument in Georgia, "which will provide laboratory space and research equipment for anthropologists working in the Southeast." [76]

Demaray's advice for Townsend and the Sul Ross campus was "to continue your active support of this Service's program." The associate director had nothing but praise for the "valuable cooperation from Sul Ross State Teachers College, the West Texas Scientific and Historical Society, and public-spirited individuals in the vicinity of those institutions." If the NPS anticipated legislation "looking toward the appropriation of funds for the construction and maintenance of a Big Bend National Park Museum," Townsend could "be of assistance in supporting the measure." Demaray added that "in a number of national parks Natural History Societies have been organized in order that they may assist the superintendent and the park naturalist in developing educational programs." The park service official considered it "entirely reasonable" for Sul Ross "to play such a role in the Big Bend." Demaray then asked Townsend to convey to Omer Sperry, Clifford Casey, G.P. Smith, and "the many others at Sul Ross who have promoted the Big Bend National Park idea" his thanks for the "good work" that they had accomplished. [77]

Additional reasons for the park service's reluctance to build a research center at Sul Ross were its isolation from population centers, and the limited academic scope of a teachers' college. In December 1940, Ross Maxwell wrote to Region III director Milton McColm about his work on the relief map of Big Bend's geology. The Geological Society of America (GSA) that winter scheduled its annual meeting in Austin, and planned a three-day visit to West Texas (without a tour of Big Bend). To correct this oversight, the Texas chapter of the GSA wanted to place a large model of the Big Bend country on display at the architecture building on the University of Texas campus. Then Maxwell noted the problem of "how to dispose of it after the G.S.A. meetings." The University of Texas had asked for the relief map, but limited funds would restrict viewing hours for the general public. Maxwell had learned that Herbert Maier of the regional office wanted to loan the model to Sul Ross College until Big Bend had proper museum facilities. The NPS geologist believed that "Dr. Morelock would be very glad to have the model for display," but Maxwell contradicted the statements of Everett Townsend by telling McColm: "My personal thought is that very few geologists visit Sul Ross and that one of the other models, like the one now in the State capitol, would be of more value to Sul Ross." The University of Texas, despite its limitations of staffing, would make a better home for the relief model, said Maxwell, "at least until we find a more [desirable] place." [78]

While President Morelock could not know Maxwell's opinion of his school's research capabilities, he did recognize in the spring of 1942 the need to promote his campus to offset budget and attendance reductions emanating from American entry into the Second World War. The president had his school produce a pamphlet on the history and programs of Sul Ross, with emphasis on the potential for scientific work. Morelock recalled how in 1923 he had arrived in Alpine to find no paved streets, "and not a single topped highway led from the town in any direction." Sul Ross at that time had only two-year teachers' certificate programs, with a library containing fewer than 1,200 volumes. "The most difficult task facing the college from its beginning," Morelock admitted, "has been lack of adequate financial support for the dual responsibility of building a creditable educational institution and at the same time taking an active part in helping to solve pioneer problems." Yet from 1923 to the fall of 1940, Sul Ross grew in enrollment from 96 students to 521 (an increase of over 400 percent), aided immeasurably by $413,000 in New Deal agency funds for building construction by the Public Works Administration (PWA) and the Works Progress Administration (WPA). [79]

President Morelock took greatest pride in his college's program development related to the Big Bend area. Seeking to imitate the regional model of the University of New Mexico, which in the 1930s pursued dreams of a national identity by aligning with the Santa Fe and Taos artists, Sul Ross opened a "Summer Art Colony" that would take students into the Chisos basin and the surrounding area. Morelock saw this as "a means of advertising Texas and for the advancement of American culture." From this institute "we should like to have scenes of our native mountains painted and placed in the public schools, in the homes, and in the art galleries throughout the country." Then Morelock spoke of his plans for laboratory facilities in geology and biology. "Every summer hundreds of geologists from colleges and universities and from oil companies all over the country," he claimed, "visit this section to examine the outcroppings of rocks of past ages." It was his dream that "a geological building on the Sul Ross campus as headquarters for these expeditions would not only be more economical in the aggregate but would accelerate scientific discoveries." In like manner, Morelock praised the work of Omer Sperry, and students like Barton Warnock, to assist the park service with its biological research at Big Bend. "Some of the largest universities in the United States," he also noted, "have permitted their candidates for the Ph.D. degree to spend at least half of their time in outdoor laboratories of the Big Bend." [80]

To ensure that readers of the 1942 Sul Ross pamphlet remembered the partnership between Alpine and the future national park, Morelock closed with praise for "the lure of the Big Bend - its romantic history, its ideal climate, the picturesque scenery of its rugged mountains, its proximity to old Mexico, and the hospitality of its people." Morelock wanted readers to know that "Sul Ross is not just another college; it has a unique environment and a distinct life." He remarked that "with good highways to this section already a reality, with a college plant representing more than a one-million dollar investment, and with an International Peace Park in the offing, and the publicity it will give to this section," the college should experience annual enrollment increases. Then in a reference to the anxieties attendant to mobilization for war, Morelock closed with a reference to Alpine's isolation as a benefit for those weary of the stress of conflict. "With the present national tendency towards decentralization of industry," wrote Morelock, "and of social and intellectual endeavor in such a manner as to provide more favorable conditions for decreasing the tempo of our modern life, educational institutions will thrive best hereafter in quiet retreats where 'plain living and high thinking' become their chief objective." [81]

By December 1942, President Morelock had convinced Arthur Kelley, chief of the park service's archaeological sites division, to visit the Alpine campus and judge for himself the potential for scientific research at Sul Ross. Kelley learned that Morelock "envisaged a collaborative arrangement with the National Park Service in which his institution with its laboratories, buildings, personnel, and other facilities for interpretation would serve as an orientation center for the millions of visitors to Big Bend National Park." The Sul Ross president defined Alpine as "the gateway to the park," with Big Bend serving as "a laboratory, a vast open-air reservoir for the original sources and natural models in place to illustrate the peculiar blend of scenic and natural phenomena." In addition, the new national park would offer "the folk atmosphere of Mexico, Spanish-America, and Anglo-America; the threshold of history in rancheria, squatter's cabin, Apache and Comanche camp sites, cave habitations of the Texas equivalent of the remotely prehistoric Basket-Makers, and beyond that the ancient hearths deeply exposed in arroyos which reflected the settlements of Early Man." [82]

Beyond Morelock's quest for a nationally prominent (and federally funded) resource program at his college, Kelley reported to the NPS director that "the dominating idea was not simply a collaboration by which there would be a division of functions between the orientation center and the natural laboratory." The NPS archaeologist stated that Sul Ross's "business is specialized in the field of producing primary school teachers." Kelley believed that "the most potent and all-pervasive educational influence which could operate to affect the largest number of highly impressionistic persons is the school teacher." He claimed that at Sul Ross, "in a Southwest setting, where many citizens are already bilingual, where four centuries of continuous cultural evolution have produced distinct but genetically related varieties of a common pattern of Spanish-American life, there is much promise for achieving an understanding between the peoples of North and Central America." [83]

As much as Kelley wanted to endorse Morelock's vision, he had his doubts about Sul Ross's capacity to deliver on these promises. "These advantages are real," wrote Kelley, "but are not mutually exclusive." He noted that "the Universities of Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona possess these same attributes in varying degree." Kelley agreed with Morelock that "the advantage of geographic position, with particular reference to Big Bend National Park, of course lies with Sul Ross." Yet "the ultimate objective of making our southwestern areas function in the over-all pattern of Pan-American cultural relations," said the archaeologist, "has a strong advocate in the University of New Mexico and Chaco Canyon National Monument." Kelley reported that the "Chaco Conference has become a southwestern institution, and as the number of visiting historians, archaeologists, anthropologists, and museologists increases, with the studied effort of the University of New Mexico to embrace the Americanists in future scientific conferences, that area tends to bulk largest in the minds of many of our neighbors." Kelley further noted UNM's effort "in salvaging the moribund Laboratory of Anthropology in Santa Fe" as "an event which needs to be evaluated by the National Park Service." [84]

Morelock's contention that proximity to Big Bend mattered more than programmatic capacity also failed to influence Arthur Kelley, who saw the Austin campus as the Lone Star state's only university with "the national and international prestige, the funds and endowments, the faculty and curriculum, and the established contacts with other institutions in Latin America." When examining UT's programs in Spanish or Latin American literature, Latin American history, political science, economics, and geography, said Kelley, "the same disproportion will be found." He also worried that "Indianization is a culturally conditioning fact in most of these [Latin American] countries which it is difficult for an Anglo-American to understand." For Kelley, "only the ethnologist, the archaeologist, or the student of sociology concerned with acculturation, can bring to these people that dignity and pride in origin and achievement which our genealogists, historians, and patriotic organizations concerned with the heroic performances of their ancestors provide." The NPS archaeologist noted that while "Teotihuacan, [and] Monte Alban are not prehistoric monuments . . . they are to the majority of Mexicans a living symbol of tribal greatness." Park service researchers needed to remember that Mexican history "is native American; ours is still unconsciously perceived to be derived European, and only secondarily by the accident of historical transplantation American." [85]

Morelock's plea to Arthur Kelley prompted the NPS archaeologist to correspond with Carl Russell, seeking the opinion of top-level park service officials. "I admire Mr. Morelock's initiative," Russell told his colleagues in Chicago, and like regional NPS officials in Santa Fe he wanted the park service to "encourage [Morelock] in his program for promoting international understanding." The NPS "will find it advantageous to establish a relationship with the Sul Ross Museum," said the interpretation chief, but he also warned that "it is a mistake to adopt a policy of excluding museums and museum work from the Big Bend itself." Russell had long held that "each National Park is a museum and that our entire Service program in each park is a specialized type of museum program." Thus "to conclude that the Service will not engage in museum work at Big Bend is irrational." If the NPS agreed to house its scientific laboratory in Alpine, contended Russell, then "it would be reasonable to say that administrative work will center at Sul Ross State Teachers College." The interpretation chief noted that Ross Maxwell had initiated a promising program of research and specimen storage. "We should strive to replace the naturalist's workshop," Russell advised, "and employ a naturalist as a member of the minimum staff first appointed." The interpretation chief saw this as "museum work even though it makes no immediate contribution to public contact work - and it cannot be done advantageously at Sul Ross." [86]

Undaunted by the opinions of Russell and Kelley, President Morelock cast about in the winter of 1942-1943 for additional support for his Big Bend-Sul Ross partnership. Two avenues that opened for Morelock were a program headed by Nelson Rockefeller, Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs for the U.S. State Department, and Dr. Emery Morriss of the Kellogg Foundation. Morelock wanted Rockefeller to establish on the Alpine campus a "Pan-American House," with its goal the promotion of "International Understanding and Good Will [a program of the Kellogg Foundation]." Newton B. Drury, director of the NPS, congratulated Morelock "on all that you have done to bring this program to the attention of important leaders in Inter-American affairs." Drury had reviewed Morelock's scheme for collaboration between the park service and Sul Ross, but believed that "you do not intend that the National Park Service should commit itself to the full extent of your statement that 'all scientific material in the park area will be placed in the museum on the college campus.'" The NPS director acknowledged that "we shall look to the talents and facilities at Sul Ross to assist with research and interpretation of the Big Bend country." As a federal agency, however, the park service could not "agree to any arrangement that would limit other scientific activities or direct the placing of all scientific materials at the College." The constraints of wartime funding prohibited any long-range planning, but Drury advised the Sul Ross president that "any postwar activities should be determined as carefully and exactly as possible." The NPS director informed Morelock of his conversations with Carl Russell, and told him that Arthur Kelley would return to Alpine "to review with you the research and interpretative programs that have been conducted in other national park areas." [87]

Morelock's quixotic search for federal support and a national identity did not abate with the caution of NPS director Drury. Three days after learning of Drury's opinion, the Sul Ross president wrote back with plans for an "International Shrine" on the border of Texas and Mexico. He then asked Drury his thoughts on "a broadcasting station in Alpine for the purpose of promoting international goodwill through the Big Bend National Park set-up here." Morelock conceded that "the outlook is a little gloomy, but if some foundation could set up the money now, we could have everything ready for a big publicity program at the proper time." The Sul Ross president had plans to travel to Fort Worth for meetings with Amon Carter, where he hoped to convince the Star-Telegram publisher to apply "a part of the $25,000 'working fund' to subsidize a station here." Morelock then informed Drury of the response that he had received from Nelson Rockefeller, who "indicated that he had referred my request for scholarship students and for money to expand our Library on International Affairs to the 'Committee on Science and Education.'" [88]

Because the park service took seriously the challenge to understand the landscape of Big Bend, NPS scientists and technicians discovered much of value in the years prior to creation of Texas's first national park. The grandeur of its canyons, and the astonishing variety of its flora and fauna, would fascinate practical people like Walter McDougall and Charles Gould as much as had the romance and drama affected Walter Prescott Webb and J. Frank Dobie. Yet the callous disregard of local landowners for these features of nature and culture angered park service officials and saddened park advocates like Everett Townsend. One ironic feature of the NPS's campaign for scientific research in Big Bend was the discovery that northern Mexico's isolation and poverty had preserved the contours of the land far better than had the ambitious nortenos. The dream of an international park may have faced severe opposition among polticians and ranchers on both sides of the Rio Grande. Yet the chance to restore an American park with flora and fauna from Mexico did not escape the notice of NPS surveyors and policymakers. Finally, the park service's power to save the land could not extend to the campus of Sul Ross State Teachers College, as federal regulations and park facility development denied President Morelock's wish for a better school, with a stronger identity, than local conditions or state funding, could make possible. It would remain for the park service to enter the "last frontier" in the summer of 1944, and to redefine land-use patterns, economic strategies, and border relations as it sought to protect one of the most striking ecological zones in North America.

| |

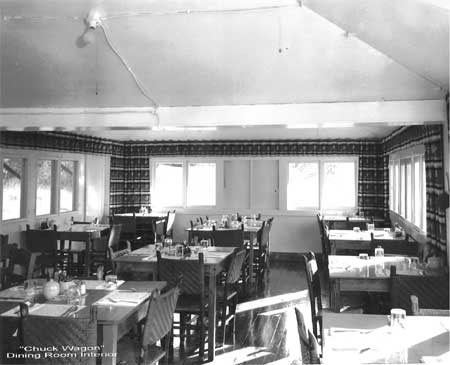

| Figure 17: First Visitor Dining Facility, Chisos Basin | |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

http://www.nps.gov/bibe/adhi/adhi12d.htm

Last Updated: 03-Mar-2003