|

FORT STANWIX

Casemates and Cannonballs Archeological Investigations at Fort Stanwix National Monument |

|

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

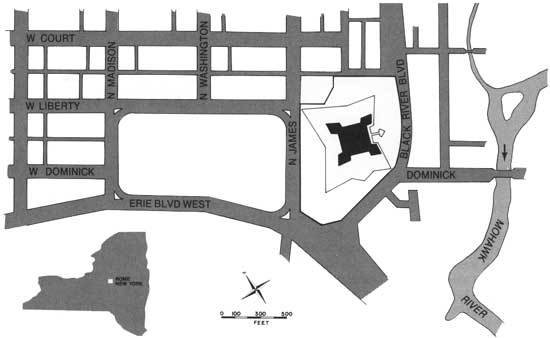

In 1965, the second phase of the Rome, New York, urban renewal project was begun, encompassing 12 city blocks in downtown Rome (figs. 1, 2). One of these blocks was traditionally held to be the site of Fort Stanwix, 1758-1781. The land was purchased and cleared by the city of Rome and donated to the Federal Government. The National Park Service prepared a master plan for the development of the site as a national monument.

|

| Figure 1. Plan of downtown Rome, New York, showing the location of Fort Stanwix National Monument. |

Buildings were scattered over the 12-block area, and it was feared that most of the fort had been destroyed by foundations and utility lines. However, excavations by Col. J. Duncan Campbell for the Rome Urban Renewal Agency in 1965 indicated that substantial parts of the fort's foundations were intact, although buried under 2 feet of topsoil (Campbell, 1965).

This report describes the archeological remains of Fort Stanwix and presents only a synopsis of the post-1781 components of the site. It is hoped that further information on these later components will be made available in future reports.

Fort Stanwix played a key role in the American Revolution, serving as a plug to one of the two main invasion routes between Canada and the American Colonies. For this reason, it was determined that the fort should be a focal point of interest during the bicentennial observance of the American Revolution. A historical report for the National Park Service by John Luzader (1969) draws together references to Fort Stanwix, its role in the French and Indian War, the American Revolution and details of construction to be used in rebuilding the fort as much like the original as possible. The records were scanty and many details remained conjectural. Archeological investigations were required to establish the location of the fort, its configuration, the interior arrangement of buildings, and to describe the artifacts left by the occupants in an attempt to supplement historical data on garrison life.

The National Park Service began archeological investigations in July, 1970, under Dick Ping Hsu. The senior author joined the staff in September of that year. Because of a lack of time and a limit to the area available for excavation (the site was still inhabited) work during the first season was concentrated on locating the fort, and identifying key features to which 18th-century plans could be related. It was discovered that the fort was not quite in the traditional location but conformed very well, internally, to the 18th-century plans. In 1896, an engineer attempted to locate the fort and, while determining its approximate position, decided that it was trapezoidal in shape rather than square as shown on 18th-century plans (figs. 4, 5, 7). Our investigations demonstrate that the fort was square. The next two summers were spent excavating the structures inside the main fort and sampling other parts of the fortifications to determine their location and dimensions. It is estimated that 33 percent of the main fort was excavated, 15 percent of which had been disturbed in the 19th and 20th centuries. An estimated 13 percent more was disturbed in unexcavated areas.

Five reference points were established in the fort area in lieu of a grid system, and all excavated features and many artifacts were mapped in relation to these stakes (fig. 10). Map tables were set up for each unit and all finds were recorded as they were uncovered. Units and sub-units were established as needed and were related to the structures found on the site. Small features, such as cellar holes or 19th-century privies were separately identified. A maximum of horizontal control was maintained, and material could be instantly identified in the laboratory as to the fort feature from which it came by the field catalog number. In the one instance where we imposed an arbitrary grid system over a structure we gained nothing in terms of increased horizontal control. It should be noted that this method can be used only in a situation where the site is highly structured and contemporary plans can be tied to the archeological work from the beginning of the excavation.

The natural stratigraphy of the site was used to maintain vertical control of the artifacts. With the exception of the ditch around the fort and pits dug into it, the stratigraphy consisted of three layers. The bottommost was a sterile, yellow-brown sandy gravel. Above this lay a thin sandy brown loam layer (Level II) containing fort debris. On top was a thick gray loam that contained 18th- to 20th-century artifacts (Level I). The entire deposit averaged about 2 feet in thickness.

The stratigraphy of the ditch surrounding the fort on three sides was more complex; essentially the same three layers were found, but instead of the brown sandy loam layer with fort debris, we encountered a dark gray loam lining the scarp, counterscarp and bottom of the ditch (Level XI). There were a series of 19th- and 20th-century strata (Levels I-X) as the ditch was filled to level the ground surface (fig. 32). The dark gray loam lining was thicker at the base of the scarp and counterscarp and was interpreted as the remains of a sod lining. In the bridge area the stratigraphy was more complex and Level XI was divisible into Levels XI-XV.

Most of the fort-related artifacts were found in cellar holes in the east and west barracks, pits in the casemates and garbage dumps on the east scarp and in the sally port communication. A few artifacts, such as gunflints, could be identified on morphological grounds as being fort-related regardless of the levels in which they were found.

Intrusions

Most sites of any size have sections that have been disturbed by later components and Fort Stanwix, in an urban setting, was no exception. The disturbance at the fort date back to the late 18th century. In 1807, Christian Schultz observed:

Rome, formerly known as Fort Stanwix, is delightfully situated in an elevated and level country commanding an extensive view for miles around. This Village . . . seems quite destitute of every kind of trade, and rather upon the decline. The only spirit which I perceived stirring among them was that of money digging, and the old Fort betrayed evident signs of the prevalence of this mania, as it had literally been turned inside out for the purpose of discovering concealed treasures (Green, 1915, p. 183).

The newspapers of the day did not record the finding of any great treasures, although from time to time there appeared entries such as the following: "Mr. Alva Mudge, who resides on the site of old Fort Stanwix, recently found a British copper in his garden bearing the date of 1738." (Anon., Aug. 15, 1879).

For the purposes of this report, an intrusion shall be defined as any post-1781 disturbance of the earth which usually, but not always, was characterized by the inclusion of post-1781 artifacts in the fill and/or an orientation aligned to the present street system. Figure 2 depicts the position of the fort relative to surrounding buildings. The buildings which were once over the fort are described below by category of intrusion. Unless otherwise noted, they were torn down in 1970 and 1971. The names of the various houses are merely convenient labels that have been traditionally applied, and are not necessarily those of the last owners of the property.

|

| Figure 2. Aerial view of the site of Fort Stanwix during excavation. The fine white line defines the periphery of the fort. (click on image for a PDF version) |

Streets

Three major streets and two alleys traversed the site, all of which covered water, sewer and gas lines at depths to 9 feet. Only the utilities under Willett Street (an alley) damaged the site since these lines ran through the center of the fort. Spring Street cut off the tip of the southeast bastion.

Cellars

Eleven major structures with cellars were located on the central portion of the fort with several more situated on the glacis. Included in this total was one indoor swimming pool built ca. 1920 on Willett Street which destroyed parts of the west barracks and west casemate. The Stryker house, built in 1839 (Waite, 1972, p. 60) had a full cellar, the digging of which destroyed the east face of the northeast bastion. The Brockett house built ca. 1842 (Waite, 1972, p. 40) had a full cellar which destroyed the east flank of the southeast bastion, a portion of the bakehouse and a large part of the 1758 powder magazine. This house was torn down in 1927. The Draper house, built ca. 1825 (Waite, 1972, p. 39) replaced an earlier structure dating from ca. 1800 (Cookinham, 1912, p. 224). It had a full basement which destroyed part of the south face of the southeast bastion and the counterscarp. The Martin house, built ca. 1878 (city directory), and torn down in 1964, had a full basement which destroyed part of the ravelin and counterscarp. The Fort Stanwix Museum, built in 1910 (city directory), had a partial basement which cut out part of the southwest casemate. The Barnes-Mudge house, built in 1828 (Waite, 1972, p. 13), had a full cellar. It destroyed most of the southwest bastion and part of the southwest bombproof. The Henderson house, constructed ca. 1870 (city directory) with a full cellar destroyed part of the west flank of the northwest bastion. The Ward house, built ca. 1841 (Wager, 1896, p. 115), was replaced ca. 1895 (city directory) by the Carpenters' Temple. Both had full cellars and destroyed part of the counterscarp opposite the northwest bastion. The Cole-Kingsley house, erected in 1846 (Waite, 1972, p. 25) with a full basement, damaged part of the north casemate and the counterscarp. Another structure, the Prince house, was erected in 1839 (Waite, 1972, p. 61) and was moved from the site in 1871 (Wager, 1871). No trace of it was found and presumably it had no cellar. The same was true of the Huntington office which was built ca. 1877 (city directory) and moved ca. 1910 to another part of the site. It was torn down in 1960. One cellar hole was found which could not be related to any known buildings. A total of 14 wood or stone lined privies were found on the site (Hanson, 1974). Most of these resulted in a minimum of damage, although one did intrude into the northwest bombproof and three others went through the gateway and bridge.

Utilities

Nine cisterns and three wells were found, but the damage from these was negligible except for one cistern in the northeast bombproof. There was also one natural gas well on the site. It was plugged as a safety measure, but did not destroy anything. A number of drain pipes and water and gas feeder lines crossed the site to service the various buildings on it. These were more of a nuisance than an intrusion, although the southwest and northeast bombproofs suffered some destruction.

Other Intrusions

A flower garden on the Stryker property left some plow scars on the east barracks. There were a number of trees on the site, particularly 13 large elms. One of these was reportedly growing from the wall of the southwest bastion in 1804 (Durant, 1878, p. 385), an observation confirmed by counting the rings when it was removed. The Dutch elm disease destroyed it before we did.

In 1965, Col. J. Duncan Campbell conducted exploratory excavations at Fort Stanwix (Campbell, 1965). He excavated the bakehouse and part of the southeast casemate. He also dug a backhoe trench through the gateway area obliterating part of it.

Organization

This report is divided into four parts dealing with the history, structural details, artifacts, and a reconstruction of life at the fort. We relied mainly on the research of John Luzader and Orville Carroll for the section on history. Inasmuch as the main purpose of excavating Fort Stanwix was to get structural information for a reconstruction, we have devoted considerable space to the layout of the fort and building design. Principal elements of the fort are presented in chapter 3 in glossary form as an aid to those readers who are unfamiliar with fort terminology. In the course of our excavations we unearthed a quantity of 18th-century artifacts left by the fort's garrisons. These offer some evidence of the activities which took place in the fort, and the technology of the period. To elaborate on the topic of life in the fort, we gathered details from orderly books, diaries and letters for the final chapter.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

archeology/14/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 02-Dec-2008