|

ANIAKCHAK

Beyond the Moon Crater Myth A New History of the Aniakchak Landscape A Historic Resource Study for Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve |

|

WORLD WAR II AND COLD WAR PERIOD (1935-1960)

|

| Aleck Abyo Jr., Mike Abyo, and Andrew Abyo, ca. late 1940s. Photograph courtesy of the Pilot Point Tribal Council, Ace Griechen Collection. |

CHAPTER NINE

From Wilderness Frontier to Wartime Front

"If we would provide an adequate defense for the United States, we must have Alaska."

—William A. Seward

After Father Hubbard and Frank Dorbandt's famous landing of a floatplane inside the Aniakchak Caldera in 1932, the Glacier Priest began to look beyond the Moon Crater for adventure. He and his collegiate crews spent the rest of the decade exploring other regions of Alaska, including additional volcanic wonders in the Aleutians, the remote King Island located in the Bering Sea, and the geological features that attracted him to Alaska in the first place, the glaciers of the Southeast. Although the Glacier Priest never returned to Aniakchak, the Moon Crater was always one of his favorite topics, especially while promoting his films or speaking to auditoriums full of excited listeners on the lecture circuit.

Throughout the 1930s, Hubbard commanded a diverse audience consisting of scientists, National Park Service personnel, and ordinary Americans seeking adventure vicariously through the Glacier Priest. After 1942, however, the U.S. military became interested in what Hubbard had to say about Alaska, especially the Aleutians. According to Hubbard, Washington D.C. had called the self-proclaimed Alaska expert to advise General Henry Harley "Hap" Arnold, commander of the Army Air Corps during World War II, and even President Franklin Roosevelt on Aleutian defenses, after the Japanese first attacked the islands of Attu and Kiska. [1] Hubbard corresponded regularly with military dignitaries such as Generals A.C. Wedemeyer, George S. Patton Jr., Air Force General Hoyt Vandenburg, Lt. General Curtis LeMay, and General Omar N. Bradley on behalf of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. [2] After the United Stated joined the war in late 1941, Hubbard offered his collection of photographs and film to the armed forces and was asked to provide information to the Army on Aleutian topography and weather. Hubbard even placed his duties as a Jesuit over his Glacier Priest persona during the war and served as an auxiliary chaplain to the Sea Bees on Attu in the Aleutian campaign during 1943-1944.

Although Father Hubbard never returned to the Moon Crater, the Aleutian Campaign of which he was a part did much to link the wilderness of southwest Alaska to the nation's wartime front in the Pacific. And like Father Hubbard and the handful of visitors who had explored the central Alaska Peninsula before him, the Army quickly discovered that the volcanic landscape was a formidable foe. As one patrol leader quipped, the defense of the region was "no Sunday-after-dinner pleasure stroll... for the jagged volcanic rock can slash the boots right off your feet." [3] Indeed, Aniakchak wilderness did far more to impede military operations on the central Alaska Peninsula than the enemy ever did.

The Air Bridge to the Aleutians

Since the United States purchased Alaska from Russia in 1867, the Aleutian Chain, consisting of nearly three hundred islands, has always been perceived by American political and military leaders as a strategic key in a long-term and potentially bitter struggle to both defend and dominate the North Pacific. [4] Charles Sumner, in a speech to the U. S. Senate on the purchase of Alaska, referred to the islands as the "stepping stones to Asia." Many military strategists, including Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan (1840-1914), suggested that because of its proximity to Asia, the United States should make the island of Kiska a naval reservation, and, indeed, in 1904, when Russo-Japanese war broke out, the army-navy Joint Board ruled that Kiska's retention would be vital in a major war with Japan. [5] After World War I, however, American military policy was shaped by intense public isolationism, even though Japan had been showing signs of Pacific expansion since Theodore Roosevelt's administration. Responding to anti-armament sentiments, the United States, Britain, Japan, France, and Italy negotiated the Washington Naval Treaty in 1922, which among other naval restrictions, banned new bases and forbade the improvement of existing Pacific facilities controlled by the signatories. The mainland of Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, and Hawaii, however, were exempted from the treaty—Alaska and the Aleutians were not. Thus, any realistic plan to place the Pacific Fleet in Alaska became obsolete, while Pearl Harbor became the center of operations for the U.S. Navy in the Pacific theater.

|

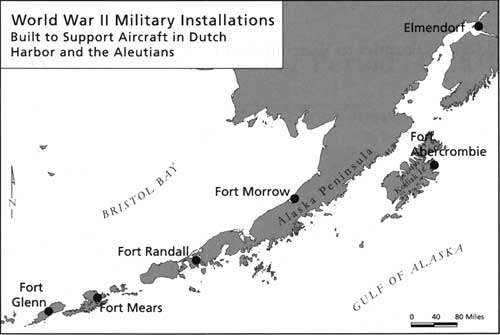

| Military bases. By B. Bundy. (click on image for a PDF version) |

In the first decades of the twentieth century, Alaska continued to be a sparsely settled territory of the United States. The population of 72,000—roughly divided between Alaska Native peoples and European-Americans—was concentrated in coastal towns, such as Anchorage, Juneau and Ketchikan, with Fairbanks being the only sizeable town in the interior. For twenty years, the Washington Treaty had limited American military interest in Alaska, and the only military-related role the federal government actually played in Alaska between the World Wars was the Coast Guard's patrol of commercial fisheries.

In 1934, however, military interest in Alaska began to heighten. That year Japan notified the Untied States that it would no longer uphold the Washington Treaty, as of December 1936. As tensions between Tokyo and Washington increased, the State Department understood quite well that the Aleutians were not only stepping stones to Asia, but also stepping stones from Asia, which could well lead the Japanese Navy across the ocean, into British Columbia and directly into the heart of the Pacific coast of the United States. Such a threat to our national security led many American leaders to believe that Japan was "our dangerous enemy in the Pacific." Aviation experts like Brig. Gen. William "Billy" Mitchell reasoned that the Japanese "will come right here to Alaska." He testified to the Committee on Military Affairs in February 1935 "Alaska is the most central place in the world for aircraft" and therefore, "he who holds Alaska will rule the world." [6]

When Japanese planes attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941, and commenced American's entrance into World War II, many believed Alaska was Japan's next step toward their goal to dominate the Pacific. And, indeed, in 1942, Japan launched a bloody invasion of the Aleutian Islands. Responding to the eastern threat to Alaska, the U.S. Army built seven airfields, ranging from Cold Bay on the Alaska Peninsula to Metlakahtla south of Ketchikan, immediately after Pearl Harbor. One of those airfields was Port Heiden, located near the village site of Meshik. Almost instantly, World War II transformed the Alaska Peninsula from an isolated frontier to a strategic American military front in the North Pacific.

In the first days after Pearl Harbor, planning by the Army was set into motion quickly. Area engineers based in Anchorage recommended to leadership in Washington D.C. that an airfield should be constructed and accommodated by a garrison at Port Heiden, to support military aircraft flying to and from bases stationed in the Aleutians. While awaiting a decision on which construction agency would be selected, Army engineers sent a reconnaissance party to the vicinity of Chignik Bay. In a letter to the commanding General of the Alaska Defense Command at Fort Richardson, B.B. Talley, a Major in the Corps of Engineers, wrote:

It is expected that a reconnaissance party will go to the vicinity of Chignik Bay to explore a possible tractor route from Chignik or Kujulik to Port Heiden for the purpose of moving in construction machinery to be used on the airfield together with the necessary supplies and other equipment for their purpose. It is not at this time considered feasible to undertake a tractor haul of building materials for a garrison, and if it should be determined that the garrison is necessary at Port Heiden in advance of the opening of Bristol Bay in the spring it is suggested that the men be housed in tents. [7]

As orders directed, the party was sent to the central Alaska Peninsula to explore a possible tractor route from Chignik or Kujulik Bay to Port Heiden for the purpose of moving necessary supplies and construction machinery to build the airfield. [8] Alec Peterson of Chignik Lagoon recalled that "a captain, a lieutenant, and about eight other guys" took a bulldozer up the Aniakchak River, where they proceeded to get stuck. According to Peterson, "the machine was there for about a month." In a second attempt, the reconnaissance party investigated the North Fork River, up which they traveled by dog team, but again failed to find a proper route. With Aniakchak Volcano as a formidable obstacle, the party did not discover an appropriate overland route from either Kujulik or Chignik Lagoon. As a result, troops and construction supplies were forced to come by way of Bristol Bay. A few days later, the Adjutant General to the Chief of Engineers authorized the Army Corps of Engineers to construct the Army base, which was officially named the Fort Morrow Air Base, in Port Heiden.

Building Fort Morrow on America's Newest Front: June 1942-1945

Orders provided for the construction of a new garrison and staging field, which was to be built within six months. The program called for containment buildings, docking facilities, and storage of aviation gasoline in drums. Housing, hospital facilities, warehouses, cold storage, and a Kodiak "T" hanger with the technical facilities to provide Air Corps operations and maintenance were also provided. [9]

On June 17, 1942, 2nd Lt. Oral B. Dold and fifty enlisted men of Company B, 807th Engineers arrived at Port Heiden with their mission to make plans for the construction of roads and to find a suitable site for the airport. [10] According to an engineer who experienced the initial landing, entering Port Heiden was as treacherous for the U.S. Army as it was for the Russian Orthodox priests:

Upon approaching Port Heiden from the Bering Sea side, a string of islands appears, stretching across the mouth of the bay. The entrance to the bay is very difficult to locate if one is unfamiliar with the locality. The entrance is located between the northeasternmost point of the string of islands and the mainland itself. The water depth in the channel varies from approximately two to eleven fathoms at low tide and the water within the bay itself is very shallow being non-navigable except in channels at low tide. Upon the arrival of troops at Port Heiden there were no buildings or structures except for the saltery, an old church, and a few sod huts at Meshik Village. [11]

Because of extreme tides and dangerous shoals situated beneath the shallow waters of Port Heiden, all ships had to anchor in the open sea approximately four miles off shore. Lighters unloaded troops and supplies. As soon as the troops reached shore, some were immediately employed in setting up a temporary campsite, while others were employed in unloading barges. Because no barge dock or mechanized equipment was available to the troops for unloading operations, all cargo was "man-handled." According to one witness, the troops experienced typical Aniakchak weather, for it was "blustery, wind and fog prevailed and the water very choppy, making the loading of barges a most difficult task." Moreover, the men were at the mercy of other natural forces, for "the loading and unloading of supplies [was] governed by the tides." [12]

The temporary campsite was established approximately three hundred yards northeast of Meshik village, with the Russian Orthodox Church substituting as the first Army Headquarters. [13] For the first few days, the troops endured the personal discomforts of living in tents and unloading by hand. The permanent campsite they would construct was necessary for the refueling and servicing of airplanes on their flights to and from the Aleutian Islands. Moreover, if an attack came from the Pacific, the men needed to be prepared as soon as possible. Fort Morrow was constructed so that it could also serve as a tactical operating base at a moment's notice. [14] Therefore, personnel were immediately engaged in preparing defense positions such as gun emplacements, foxholes, slit trenches and barbed wire entanglements along the Port Heiden beachfront. [15]

Two days later, Chaplain Joseph Applegate of the 1st Battalion 53rd Infantry held his first services at Fort Morrow, Alaska. According to an observer, "there were seven services during the day, the most inspiring service being held on the beach. The men working, unloading barges, moving material, stopped and assembled among oil drums and supplies to listen to the word of God in the wilderness of the north." [16] Apparently, an artist, Cpl. Warren Leopold, caught this scene in one of his paintings, which as one officer noted, depicted the life of the men forming a post on America's newest front. [17]

* * *

|

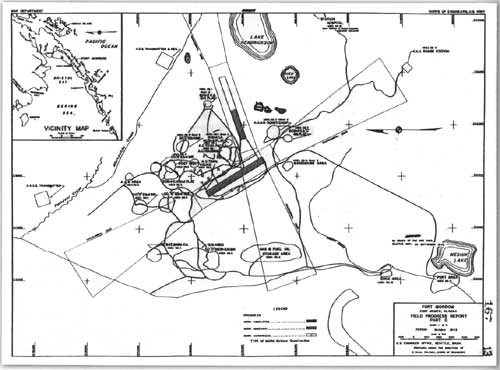

| Corps of Engineers, U.S. Army, Fort Marrow Field Progress Report, 1943. From Fort Morrow Project Report. Courtesy of Elmendorf Air Force Base, Anchorage, Alaska. |

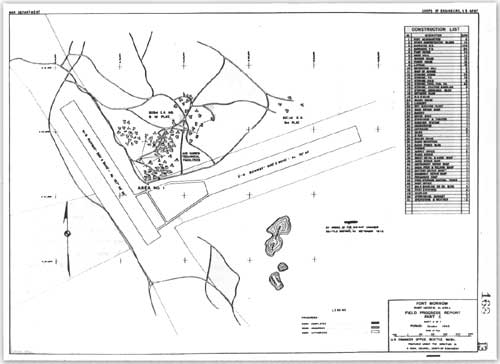

After investigating the surrounding landscape, engineers determined that Fort Morrow would be built on a site five miles from Meshik Village, and on July 22, 1942, construction personnel broke the first ground. To accommodate transport vessels, troops built a temporary unloading ramp from materials obtained from the saltery at Meshik Village. [18] While the airfield was still under construction, the first military aircraft was able to land at Fort Morrow exactly one month to the day after the building of the runway began. At 10:45 a.m. on July 22, an Army transport plane touched the partially completed North-South runway. This runway, which was five thousand feet long and five hundred feet wide, was completed in November 1942. It was then decided to construct an East-West runway of the same dimensions, and then extend both runways to 7,500 feet. [19]

Construction of roads and runways, not to mention the completion of simple daily tasks, was always an arduous proposition for the Army regulars stationed on the Alaska Peninsula. Several historians have noted that the Aleutian campaign of World War II was a three-sided battle fought between the United States, the Japanese empire, and a force that proved to be more powerful than either Washington or Tokyo: the weather. [20] On the central Alaska Peninsula, not only did troops endure rain, dense fog, thick mists, and the severe gale-force winds, the williwaws, but Aniakchak's volcanic landscape served as a logistical and strategic obstacle as well. In an Army report, an engineer matter-of-factly described the immediate surroundings:

The terrain, commencing at the beach, consists of rolling dunes joining the beach with a shelf of small hills running parallel to the shoreline. As the shelf moves inland, it levels off away from the rolling hills and declines into a surface of tundra, swamps and volcanic ash. Although the landscape surrounding Fort Morrow is relatively level land, intermingled swamps and small streams continue for approximately ten miles inland. It is at this point where engineers attempting to build roads and runways encountered a first gradual, and then steep incline towards Aniakchak. [21]

Engineers, however, found the materials underlying the tundra—a mixture of pumice rock, of pebbles size, and volcanic ash—to be "an excellent building material, compacting easily and not softening appreciably during rainy weather." [22] Nevertheless, blizzards and below zero temperatures caused the ground to freeze to a depth of thirty feet, retarding the progress of runway construction. The unloading of supplies and equipment from transport vessels some four miles distant from shore and ongoing lighterage operations continued to be handicapped by frequent high winds and low temperatures. Transports arriving during the fall season often could not unload, due to the freeze-up of the bay. Sea-going freight could only be delivered during six months of the year. Due to the floating ice blown in from Bristol Bay, the small dock made from materials gathered from the old saltery was destroyed and had to be rebuilt during the summer of 1943. According to fort commanders, Aniakchak's volatile climate considerably delayed construction of the entire project. [23]

Despite the environmental obstacles, between 1942 and 1943, the Army had transformed the Aniakchak landscape surrounding Port Heiden into a working air base. By the end of summer, 1942, the Army established a weather reporting station. During September and October, the Civil Aeronautics Authority (CAA), the predecessor to the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), made a survey for a radio range, control tower, radio station, and hangar — facilities that contributed to the safe landing of Army personnel, including Major General Simon Buckner and Colonel Lawrence Castner, who visited Fort Morrow on September 4, 1942. [24] By February 5, 1943, the range station was completed. On the same day, the Army Airways Communion System commissioned a point-to-point and air-to-ground facility, further improving the control over planes in the area after the control tower was commissioned on November 15, 1943. On the same day, the hangar was also completed. In late 1943, the installation of runway boundary marker lights was finished. [25] That year, Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia of New York City, who arrived with Brigadier General Frank L. Whittaker, visited Fort Morrow. Apparently, they stayed for one hour. [26]

Fort Morrow's Major Battle: The Aniakchak Wilderness

The first Air Force personnel to arrive for duty at Port Heiden were two weathermen. Their main duties were to collect and disseminate weather data to other weather reporting stations. Early in October 1942, Captain Ralph F. Gandy arrived with nine enlisted men. These men formed the nucleus of the Air Base and were responsible for base operations. By mid 1942, forty-three officers, nine medical officers, one chaplain, one warrant officer, and 1,353 enlisted men were stationed at Fort Morrow. By 1945, that number increased to 1,895 enlisted men and eight additional officers, a medical officer, and a chaplain. [27]

Despite duties, which included refueling and servicing airplanes going to and from the Aleutians, personnel at the Port Heiden base apparently felt frustrated, and, at times, even disconnected from the rest of the war. Certainly several embarrassing military blunders, including the anti-climatic invasion of Kiska in 1943, produced feelings that the Aleutian campaign "tied down enormous resources that could be better used elsewhere." [28] Adding to their discontent was communal gloom caused primarily by the inclement weather that seemed to cloak the region. In his history of World War II, historian Samuel Eliot Morison called the Aleutian campaign the "Theater of Military Frustration" and claimed, "Servicemen sent to the Aleutians regarded an assignment to this region of almost perpetual mist and snow as little better than penal servitude." [29] Likewise, such disillusionment was felt at Fort Morrow, as troops struggled to adjust to a foreign environment.

In early October 1944, the base was hit by a heavy storm, in which the wind velocity reached eighty-eight miles per hour. One warehouse and the generator hut were blown down, leaving the area without power for two days. Hangar doors were blown off or buckled, tarpaper was ripped off many roofs, and oil drums were distributed over the landscape. One drum was even carried through a window into one of the barracks. Fortunately, no one was injured in the storm, but, thereafter, "strict discipline has been enforced due to the effects of isolation on morale." [30]

One Chignik Bay resident, Emil Artemie, recalled an episode in which he encountered potential deserters from Fort Morrow. His recollection clearly illustrates the loneliness and discontent, spawned particularly by the unfamiliar surroundings experienced by the troops. According to Artemie, he encountered several young enlisted men, who approached him with questions:

You'd be surprised the kids that were in the service during the war. Just kids, some of them. Eighteen years old. And some of 'em had never seen an ocean in their lives. We could tell. They used to stop down the Bay and they ask[ed] me one time... a couple of them came ashore and I was at the beach working on a skiff or something. "Can we walk to Seattle from here?" I suppose you could, [I said], but it's going to be a very long walk, (Laughs) I figure they thought there might be a highway out on the other side of the mountains, maybe. Anyway, there was four or five of them. [They] took off. Seen them packing their gear [in an] old skiff they got holed up under the dock in the afternoon. But they took off, pretty soon I seen them, there at the ridge of the mountain down the Bay.

Evidently, the young men did not get far. "They come back in the evening," recalled Artemie. "Their skipper" [probably their commanding officer] just say, 'Welcome back, boys.'" [31]

Not all of the enlisted men felt isolated by the Aniakchak landscape, however. According to base records, four twelve-gauge shotguns were made available to the enlisted men, with which they were allowed to hunt local birds and game. Apparently, the men enjoyed many feasts on duck, goose, or ptarmigan. Fresh caribou was also obtained, increasing the attractiveness of some of the meals at the mess hall. [32] Although rain and wind discouraged most outdoor activities, many enlisted men enjoyed fishing the local steams, encouraged by "occasional catches of fair-sized Dolly Varden or rainbow trout." [33] Fresh salmon for the mess hall were caught on several occasions from nets tied to barges by the dock. [34] On days that brought a welcome break in the usual gray skies, a spell of excellent weather encouraged activities such as softball, volleyball, and beachcombing for "ivory and Japanese glass net-floats." [35]

The Army also tried to improve morale with better living and recreation facilities. From 1943 to 1945, enlisted men enjoyed facilities such as a complete mess hall, recreation hall, a barbershop, and a local "miniature" radio station, which used the call letters WSIO. Enlisted men watched movies at the base theater and read books at the base library, which according to the historical officer was "tastefully decorated, well lighted, and replete with comfortable overstuffed furniture." In 1944, a USO troupe arrived at Fort Morrow and put on four performances for the enlisted men stationed there. Another troupe arrived the following year with "skilled magicians, singers, even Joe Louis." [36] USO dances were not only popular among the enlisted men, but local women from Port Heiden and Chignik attended them as well. According to Pat Partnow, "During and immediately after the war a number of romances and marriages occurred as a result of these meetings, the aftermath being the departure of many young women from the peninsula to destinations to the south." [37]

When news reached Fort Morrow that allied troops had gained victory in Europe during the spring of 1945, the day was celebrated as a special holiday with free beer and buffet lunch all day at the mess hall. [38] Then, on September 4, 1945, less than a month after the American B-29 Enola Gay dropped an atomic bomb over Hiroshima, Japan, and effectively ended World War II, Brigadier General Paul E. Burrows returned to Fort Morrow for a brief visit. At a meeting with all base personnel in attendance, he informed Fort Morrow's officers that it had been decided that the base would be closed as an Army post. As one witness recalled, "though there was no demonstration at the time, everyone was overjoyed at the prospect of returning to a more cheerful part of the world." [39] On October 7, 1945, orders arrived, officially inactivating the Army Air Base, Fort Morrow. [40]

The Impact of World War lion the Aniakchak Region

Aniakchak's surrounding landscape clearly had an impact on the daily lives of the soldiers stationed at Fort Morrow, but World War II also had a reciprocal effect on the everyday lives of the residents who called the central Alaska Peninsula their home. Many of today's elders, who were children during the war, consider those four years as the watershed between the old rural lifestyle and modern American culture. [41] Afterwards, as Partnow points out, "transportation, communication, and American cultural influences expanded in unforeseen directions and dimensions." [42] Perhaps the most significant outcome of World War II was that peninsula communities would forever be tied to the rest of the territory (the state after 1959) and the rest of the world.

|

| Corps of Engineers, U.S. Army, Fort Morrow Field Progress Report, Part C, 1943. From Fort Morrow Project Report. Courtesy of Elmendorf Air Force Base, Anchorage, Alaska. |

Between 1941 and 1945, local people seemed not to worry about inland volcanoes as much as a looming threat from beyond the waters of the Pacific Ocean. As a result, Aniakchak residents played a patriotic role in Americas war effort, whether it was supporting the U.S. campaign to buy bonds, leading blackout drills at home villages, or joining America's armed forces. In 1943 it was reported that Kanatak elders convinced the village's younger generation to support the American war effort:

Mrs. Alta C. Wilder, schoolteacher at Kanatak, gives us a dramatic insight into the depth of the Aleut's [Alutiit] devotion to the country. She called a meeting and explained about the bonds. After she had finished, an old man took the floor, then an old women. . . . After length monologues, the old people sat down. Deep silence followed. ... Mrs. Wilder asked the young interpreter what they had said. "The old man and the old woman say they know the government is good." ... "And," asked Mrs. Wilder, "what do the younger ones reply?" "The youths' answer was brief. 'They say, we agree.'" [43]

|

| Landing Strip at Fort Morrow, circa 1950s. Photograph courtesy of Elmendorf Air Force Base, Anchorage, Alaska. |

The Alaska Life article was clearly written as a wartime propaganda piece. Still it shows the degree of Alaska Native participation during World War II, and speaks well of the patriotism and hopefulness of that generation of Alaska Natives. [44] Admittedly, it was a fearful time for Alaska Peninsula residents, especially for the young. Chignik Lagoon resident, Peter Lind, who was a child during World War II, remembers how nervous villagers were during the war and how quickly rumors spread about the possibility of a Japanese invasion:

One time we were down the lagoon. We were all sleeping. And my uncle, used to live next door, all of a sudden I wake up, somebody was hitting the windows real hard. Ask Mary this, she probably still remember that. Real hard, she said "Japanese. Japanese. It's on the beach." I jumped up and was half asleep and mom... We had a kerosene lamp and it was on, I jumped up and turned it down you know. Momma would turn it up, I turn it off. She was still hollering in through the window, nighttime. The door was locked. And we woke up. This was really scary. And we could hear the boats down the beach. Making noise. Then, they hit the beach, the tide was high. We lived a little ways from the water, you know, down the lagoon. They even stopped. That lady said there's Japanese down the beach, you know. Holy man, I was scared! I was almost half kinda hanging onto mom. I was small. And we were sitting down in the house and pretty soon somebody knock on the door. Dark nighttime you know my mom want to go answer it. I told her not to, I was hanging on to her. When she opened the door you know you it was? My brother Skipper. He came to Chignik to go check on us, see how everybody was doing. [45]

Rumors of invasion were indeed rampant, but for many Alaska Peninsula residents, the war was all too real and played an enormous role in shaping their lives. Young people from all over the Alaska Peninsula served in the armed forces throughout the territory and other parts of the world. Peter Lind's older brother joined the war effort. "My brother, Andrew, they took him in a tug boat to Cold Bay. And, boy, my mom used to worry. He was the oldest one, you know. They took him to be a ... deckhand in tugboat. Hauling equipment." [46] Moreover, as with civilians from Europe or the West Coast of the United States, the residents of the central Alaska Peninsula knew that if the enemy did attack, they would come by way of an airplane.

Every time we hear airplane me and my brother used to hide in the bushes it was so bad. Just the time they were coming, Japanese was invading from down there. [Dutch Harbor]. We used to play boat in the creek. And we hear airplane, I'm not kidding, it got so bad, we would run in the bushes and wait. One time we were picking berries with my mom, and Jr's mom. Us kids. And the men were fishing. We were picking berries up the hill. And we look, and we seen two little dots coming, getting closer and closer and closer. And my mom took us and threw us in those holes. Threw us in there to hide us. And we were watching there those two fighter planes. You could even see the people inside there with guns. But, they were our own airplanes. Boy, I was scared. Holy Cow! [47]

Just the sound of an engine stopped people in their tracks. "When we hear airplane, the whole village would run out and watch it." [48] Similar to protocol everywhere, villagers in Chignik implemented blackouts, which were broadcast over the local radio. "No lights," recalled Lind. "The houses. Even in the sod houses. Turn all the lights off." [49]

Besides representing a threat, real or imagined, the role of aviation on the Alaska Peninsula changed significantly during the war years. Local pilots, for example, were incorporated into the war effort. At first integration was sporadic, with local flyers primarily used for search and rescue operations. As one incident illustrates, on April 20, 1945, a fighter plane had to make an emergency crash belly landing some forty miles north of Fort Morrow. The pilot was uninjured, but was in a spot inaccessible by foot or land vehicle because of the surrounding lakes and muskeg. Two days later, the Air Base commander called in a civilian pilot, who was able to bring his light float-plane down on a swamp near the wreck. The pilot was then able to land on Meshik Lake near the Base, returning the Lieutenant to "civilization" soon afterward. [50]

As the war progressed, commercial aircraft, like those used by Frank Dorbandt and Harry Blunt to fly Hubbard around the Alaska Peninsula, were pressed into military service. By 1943, the Army began to utilize most local pilots on a daily basis, to fly personnel from base to base and to transport repair parts that were immediately needed. One of those pilots was Bob Reeve, the famed Glacier Pilot, who made his first flight out to Cold Bay soon after Pearl Harbor. Before World War II, most Alaskan flyers considered the Alaska Peninsula "a piece of rock—nothing surrounded by nothing." Before flying for CAA, Reeve had flown down the Alaska Peninsula only as far as Bristol Bay and Port Heiden. "To us in the old days, both the peninsula and the Aleutians were considered 'nowhere.' No one went out there except on rare occasions." [51]

Once they were flying for the military, civilian pilots made the trip down the Chain so often that personnel stationed at their various stopping points quickly welcomed them and considered the flyboys as one of their own. As biographer Beth Day notes, "Reeve made a practice, as he had done for the miners, of bringing out personal items they needed or simply wished for: film for their cameras, cigarettes, magazines, liquor. Frequently fogged in at the Chain bases, Reeve spent many a night helping the boys pass time over bull sessions at poker tables." [52]

The integration of Reeve and other civilian pilots into the U.S. Army during the war years not only helped to bring the peninsula into the American fold once and for all, but it changed the character of aviation on the peninsula. In a sense, Father Hubbard's flight down the Alaska Peninsula in 1931 initiated a short ten-year span representing the so-called "golden age" of pioneer aviation in the Aleutians, the Alaska Peninsula, and the Aniakchak region, which the bombing of Pearl Harbor abruptly ended. According to aviation historians, "the influx of military activity in Alaska led to construction of modern airfields, and to the improvement of communication and navigation aids throughout the territory." [53] The four-year period that encapsulated World War II brought a massive increase of people to the central Alaska Peninsula. When it was over, the military scaled back to a skeleton crew in Port Heiden, but the commercial aviators, who took advantage of the infrastructure that had been put in place by the military, eventually merged and consolidated their small air services into larger conglomerates, thus, bolstering a successful commercial air industry that exists to this day.

"Air Highway that Americanized the Village"

Although it lasted less than four years, World War II left an indisputable mark on the Aniakchak region. Besides ending Alaska's "golden age of flight, changes in world politics provided the Aniakchak region with a new role in national security. As the "Hot" War turned "Cold," military strategists were more than aware that the next threat to the United States—the Soviet Union—sat only a mere 60 miles across the Bering Strait from Cape Prince of Wales, near Nome. The realization thrust Alaska back into the national defense spotlight, and thusly, linked Aniakchak to a federally controlled long-line communications system in Alaska. Not since Bering's landfall had Americans been more aware of Alaska's proximity to Russia.

During the Korean conflict, Congress appropriated $11.7 to $14.4 billion annually to support the military's needs. By 1953, the amount jumped to $50.4 billion, and much of the purse was spent on the defense of Alaska. The increase in funding allowed the Alaskan Air Command to begin to build a permanent aircraft control and warning system to improve communications in Alaska's remote sites. [54] The Air Force base at King Salmon, for example, became a radar site as the military began to centralize control of advanced warning. The Air Force placed King Salmon on a standby status and authorized it to respond to any hostile activity initiated by the Soviets in U.S. air space. [55]

In addition to the Alaskan aircraft control and warning systems, the Air Force embarked on a program to build a system of distant early warning radar sites across the Canadian arctic and northern Alaska. In his study, Top Cover for America: the Air Force in Alaska 1920-1983, military historian John Haile Cloe states that the Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line, as it became commonly known, "would provide early warning against bomber attacks coming over the polar regions." [56] The Air Force began to work on the DEW Line in northern Alaska in 1953. In January 1957, the Joint Chiefs of Staff approved the extension of the DEW line into the Aleutians. The main site was at Cold Bay with auxiliary sites at Nikolski, Port Moller, Cape Sarichef, Driftwood Bay, and Port Heiden. Work was completed in early 1959, and the sites were turned over to Alaska Air Command control on May 1, 1959. Unlike the northern sites, AAC retained responsibility for the operations and maintenance of the sites. Also, unlike the contractor-manned northern sites, military personnel manned the Aleutian sites. [57] About one hundred people maintained the Port Heiden Dew Line site.

|

| Port Heiden became part at the defense line know as White Alice during the Cold War era. Photograph courtesy of Elmendorf Air Force Base, Anchorage, Alaska. |

The central Alaska Peninsula became even a tighter link in the military chain when military leaders extended a communications system known as White Alice into the region. To improve communications between Alaska's radar sites, the military contracted AT&T to develop a reliable communications system for Alaska. According to Cloe, the communications firm decided on a new system called troposphere scatter, which bounced radio signals off the troposphere. [58] In 1955, The Western Electric Company began to build several "tropo" and microwave sites which would connect Alaska's air defense sites. In the 1960s, the communications system was extended down the Aleutians to support the Dew Line segment, and Port Heiden became part of White Alice as a repeater station. As communication technology improved, commercially owned satellite terminals replaced all the tropo sites by 1981 and, the tropo sites, like the one at Port Heiden, were eventually terminated.

* * *

World War II and the years that followed brought enormous change to the Aniakchak region. The Alaska Peninsula's geographical proximity to both Japan and the Soviet Union gained attention from the U.S. Armed Forces, which ultimately transformed its perspective of the appendage from a wilderness frontier into a strategic military front. For its inhabitants, the threat from the Far East made the villagers of Chignik far more aware of the outside world, and indeed, the Aleutian Campaign brought the outside world directly to the Alaska Peninsula. New communication and aviation systems were constructed, thus reestablishing the peninsula's older role as a "bridge to the Pacific." Perhaps most significantly, World War II enhanced Alaska's visibility and transformed its economy. As historian Dan Nelson notes, "Spending for bases, supplies, and salaries became the engine for a new boom and revived [Alaska's] get-rich-quick spirit of the gold rushes." [59] War activities brought people to Alaska, as the gold rushes of the previous century had done. The territory's population rose from 73,000 in 1939 to 233,000 in 1943. And instead of a peacetime bust, the Cold War inspired a new wave of federal spending that totaled more than a billion dollars in the 1950s. [60] As government jobs increased both for military and civilian personnel, people remained in the territory.

Thus, it was the Air Force base at Port Heiden that brought many local people back to the central Alaska Peninsula. Scott Anderson, who runs an environmental program at Port Heiden, points out that the village of Meshik was for the most part, abandoned following the 1919 Spanish Flu epidemic until World War II. After 1941, the military not only brought people back, it brought people together: "It made the first schools and medical facility available to local residence. It built roads and the airstrip and fostered positive community relations." [61] Anderson went on to say that Army personnel often carried small pieces of candy in their pockets for local children.

Similarly, King Salmon-based pilot, George Tibbits, recalls that the DEW-line site station at Port Heiden was very nice." According to Tibbits, it was a place where residents could purchase everything from "fuel to food, even watch Hollywood movies." As a pilot, Tibbits had no problem recognizing the role that the string of Army bases played in the history of the Alaska Peninsula. When asked about the importance of the military presence at Port Heiden, the pilot responded without hesitating: "It built a highway that Americanized the Alaska village." [62]

NOTES

1Price, "Adventuring with the Glacier Priest," 117.

2Hubbard kept a binder featuring correspondence from highly placed military officials. CPA collection; Price, 117.

3Press Release, Headquarters United States Army, 401-07 23rd Infantry, file FRA PAO, APO 949, July 2, 1962.

4Galen Roger Perras, Stepping Stones to Nowhere: The Aleutian Islands, Alaska, and American Military Strategy, 1867-1945 (Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 2003), xi.

6Ibid., 30; John Haile Cloe also discusses Alaska's strategic position in his classic study Top Cover for America: The Air Force In Alaska 1920-1983 (Anchorage: Air Force Association and Pictorial Histories Publishing Company, 1984), 1.

7B.B. Talley, Major, Corps of Engineers, Area Engineer, to the Commanding General, Alaska Defense Command, Fort Richardson, Alaska. Fort Morrow File, Elmendorf Air Force Base.

8Eugene Barbie, "History of the Air Base Fr. Morrow Port Heiden, Alaska," December 1941 to 31 May 1944, 3. Document located at Elmendorf Air Force Base, Anchorage, Alaska.

9"Bush Report," Fort Morrow Project, pg. 165-166, in the Fort Morrow File at Elmendorf Air Force Base, Anchorage, AK.

10Eugene Barbic, "History of the Air Base Fr. Morrow Port Heiden, Alaska," December 1941 to 31 May 1944, pg. 3, located at Elmendorf Air Force Base, Anchorage, Alaska.

11"The History of Fort Morrow from its inception on 17 June 1942 to 1 July 1944," Historical Report, pg. 2, located in the Fort Morrow File at Elmendorf Air Force Base, Anchorage, AK.

12"History of Fort Morrow Alaska," 2

14Barbic, "History of the Air Base Ft. Morrow Port Heiden, Alaska," December 1941 to 31 May 1944, 1.

16"A History of Fort Morrow, Alaska," pg. 2, from the Fort Morrow File located at the Elmendorf Air Force Base, Anchorage, AK.

17"History of Fort Morrow Alaska," 2

20Ira F. Wintermute, "War in the Fog," American Magazine, August 1943, 9; also see Terrence Cole's depiction in the foreword to Brian Garfield's popular history, The Thousand Mile War: World War II in Alaska and the Aleutians (Fairbanks, University of Alaska Press: 1995), xi.

23Fort Morrow Project, "Bush Report," 166.

24"History of Events" pg. 4, Fort Morrow History on file at Elmendorf Air Force Base, Anchorage, AK.

27Post Headquarters Fort Morrow Alaska, History of Fort Morrow, Alaska Period Ending Dec 31, 1942;???

29Samuel Eliot Morison, Aleutians, Gilberts and Marshall's June 1942-April 1944, in History of United States Naval Operations in World War II (Vol. 17), (Boston: Little, Brown, 1951), 3-4.

30Commanding officer Reginald Bowles in the forward to John Shield's, "History of the Army Air Base, Fort Morrow, Port Heiden, Alaska, 1 October 1944 to 31 July 1945." 1. Elmendorf Air Force Base, Anchorage, AK.

31Pat Partnow's interview with Emil Artemie. January 24, 1992. ANIA File, Lake Clark Katmai Studies Center, Anchorage, AK.

32John Shields, "History of the Air Base Ft. Morrow Port Heiden, Alaska 1 June 1944 to 30 June 1944," 12.

33Shields, 1 August 1945 to 31 August 1945, 4.

39Shields, 1 September 1945 to 30 September 1945, 2.

40Shields, 1 October 1945 to 7 October 1945, 2.

43Bess Winn, "Alaska Natives in the War" Alaska Life (July, 1943), 7-11.

44For information about Alaska Natives at War see Paul Ongtooguk's work at www.Alaskool.org.

45Peter Lind interview with Partnow, ANIA File, Lake Clark Katmai Studies Center, Anchorage, AK.

50Shields, 1 October 1944 to 31 July 1945, 5.

51Beth Day, The Story of Bob Reeve Glacier Pilot (Sausalito, CA: Comstock Editions, Inc., 1957), 190.

53Alaska Geographic, "Frontier Flight," 38.

54John Haile Cloe, Top Cover for America: the Air Force in Alaska 1920-1983 (Anchorage Chapter Air Force Association and Pictorial Histories Publishing Company: 1984), 160.

59Daniel Nelson, Northern Landscapes, the Struggle for Wilderness in Alaska (Washington D.C.: Resources for the Future, 2004), 24.

61Scott Anderson, personal communication, 2004.

62George Tibbits Jr. personal communication, 2004.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

hrs/chap9.htm

Last Updated: 03-Aug-2009