MENU

Gettysburg

| Mission

66 Visitor Centers

Chapter 3 |

|

Designing the Visitor

Center and Cyclorama Building

A few years after receiving the commission for the visitor center and cyclorama building, Richard Neutra recalled his initial thoughts about the future "shrine of the American nation." Like Mission 66 planners, Neutra believed modern architecture could fade into the landscape, leaving the park to display its historical legacy without interference. "Our building should play itself into the background, behind a pool reflecting the everlasting sky over all of us—and it will not shout out any novelty or datedness." [21] Modernism was bolstered by the theory that advanced materials and sophisticated technology would satisfy basic human needs, leaving nature and history undisturbed. Modern architecture attempted to "play itself into the background," not with a rustic disguise, but by minimizing the excess of such contrived designs. Shorn of all ornament and without the distraction of gingerbread or peeled logs, modern buildings pretended to be nothing but functional spaces, the very simplicity of which became their aesthetic. If the modern style broke with the Park Service's architectural tradition, the theory behind modern architecture mirrored the goals of the Mission 66 program. In retrospect, modernism could hardly live up to all of these lofty aspirations, but in the 1950s, Americans still expected an architecture transformed by technology. Throughout his many books and essays, Neutra expressed faith in the power of good design to "see organic evolution continued" and "check the technical advance in constructed environment." [22] Neutra's theories about the relationship between people and their surroundings may have made his work particularly attractive to Park Service planners.In his memoirs of the Gettysburg commission published before the building's dedication, Neutra recalls receiving a phone call from Washington while traveling through the Arizona desert. He spoke with Secretary of the Interior Fred Seaton and Director Conrad Wirth about the building, and later personal meetings helped him to develop a design. The firm of Neutra and Alexander produced a set of preliminary drawings for the visitor center and cyclorama dated April 28, 1958. A "master plan development" drawing completed by the Park Service just the week before shows the footprint of the building oriented as the partners planned, with the rotunda end facing the High Water Mark. The general site layout also showed a road from the parking lot to Meade's Headquarters, the existing observation tower on the edge of Ziegler's Grove, and a portion of the National Museum to the north of Hancock Avenue. [23]

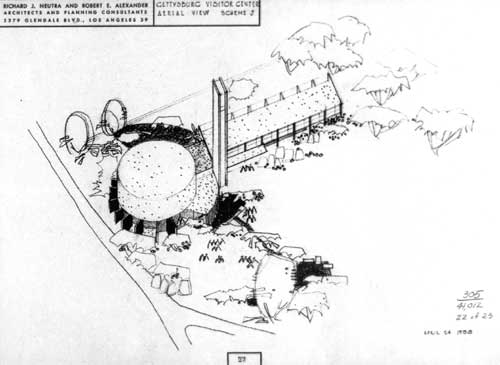

Figure 30. This preliminary drawing for the visitor center was part of a set of twenty-three sketches completed by Neutra and Alexander in April 1958. Note the nine-story observation tower and the orientation of the building.

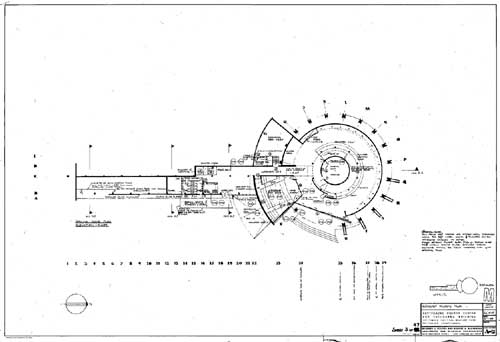

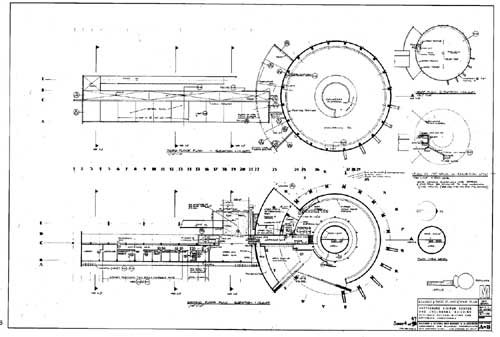

(Courtesy National Park Service Technical Information Center, Denver Service Center.)In their first set of drawings for the visitor center and cyclorama, which included some sheets labeled "scheme J" and some "scheme K," Neutra and Alexander imagined a building similar in structure to that actually built, but significantly different in terms of visitor experience. The visitor center was located on the site indicated by the slightly earlier Park Service drawing: the rotunda just feet away from Meade Avenue and the space reserved for "gatherings" parallel to the road but sheltered by a stone barrier. The first scheme placed the office wing nearest the parking lot so that approaching visitors could enter the roof deck viewing area immediately or proceed to the main entrance. The outdoor promenade continued around the rotunda. Visitors could take an elevator up a slim nine-story tower located between the office wing and cyclorama. A pool was planned at the transition of the horizontal and cylindrical building forms. Circulation diagrams emphasized the visitors' approach from the parking lot to the entrance, as well as around, inside, and outside the building; the battlefield could be studied on different levels and from multiple perspectives. The set of plans also included a list of museum exhibitions, labeled and numbered from one to twenty-three.

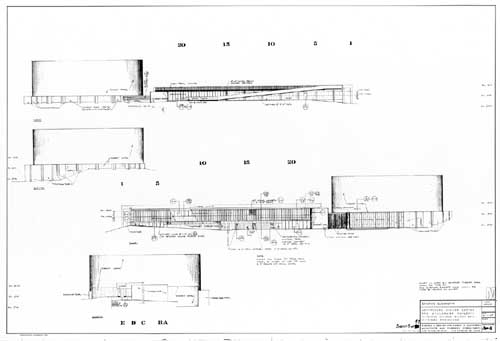

Although the firm's general idea gained approval, the Park Service preferred a less conspicuous version of the design. The partners worked on revising drawings over the next year, finally submitting a second set dated June 1, 1959. [24] In an effort to minimize the rotunda, the building plan was flipped so that the cylinder was partially sheltered by the grove of trees. The viewing tower and rooftop promenade around the rotunda were removed from the program. In the revised design, the viewing deck offered a clear vista of the battlefield, but the entrance to the deck was no longer so obvious. The architects attempted to improve the ramp situation by adding a system of reflecting pools, one of which paralleled the viewing deck. According to project architect Dion Neutra (Richard Neutra's son), this was an effort to "entice people to disperse themselves along the length of the building to view the battlefield" and thereby avoid "the crush at the top of the ramp." [25]

Throughout this revision, the firm envisioned the contrast between the building's modern materials—steel, glass, aluminum, and concrete—and the random masonry walls and panels built of local stone. In the design of their courtyard stone wall at the Painted Desert Community, the architects looked to ancient desert dwellings for inspiration. At Gettysburg they also attempted to integrate regional building traditions and planned to find a suitable example of local masonry in a nearby historic building. During the next two years of construction, the architects became obsessed with perfecting the stone walls based on the selected historic prototypes. This relatively minor aspect of the finished building represented something more to the architects. It was both a departure from Neutra's earlier work and, perhaps, a concession to the unique park site.

The specifications for the revised visitor center included a "personal word to the bidder" intended to encourage good faith and open communication throughout the construction process. The firm anticipated that contractors might find certain unfamiliar practices in need of clarification. In an addendum to the specifications produced about three months later, Neutra and Alexander described an extra artistic flourish: the addition of a final spray coat of glitter finish applied directly to the wet cement with a "specifically designed spray gun." The glitter was small flakes of "diamond dust" (mica) applied to the white areas of cement at a concentration of four to five pounds for each hundred square yards of surface. The addendum also included explicit instructions for the design of the ribbed concrete and the elimination of any form marks that might interfere with the vertical pattern. For the next three years, the contractors and architects would struggle with these requirements. Along with the technical specifications, the firm developed a more artistic presentation of the building for the client. Neutra created a pastel rendering of the building from the Hancock Avenue approach; the white form accented in turquoise and purple was surrounded by green grass and a forested background. [26] The architects also produced a brochure with studies of the cyclorama building, a copy of which was sent to Superintendent Myers. [27]

Figure 34. "Gettysburg Visitor Center, view from the east," pastel by Richard Neutra, 1959.

(Courtesy National Park Service Technical Information Center, Denver Service Center.)Since the project's early planning stages, Mission 66 planners had anticipated many benefits from their new visitor center and cyclorama, but they also worried about the impact of growing numbers of tourists and businesses attracted to the area. The 1960 Master Plan articulates some of the park's concerns about modernization, pointing out that "Gettysburg's popularity has meant increasing commercial and housing development which, even now, is destroying its attractive rural character and detracting from the Park itself." [28] Although complaining bitterly about private enterprise and the excesses of "commercialization," the Park Service was enthusiastic about its own modern roads and visitor facilities. If these were intrusions on hallowed ground, the benefit of necessary improvements would far outweigh any damage. The new visitor center would serve as the "initial point of contact and orientation," a role facilitated by its location at the juncture of six highways. Visitors could "refresh their memories on the stories of the battle and the Gettysburg address, obtain literature, and, if they wish, the services of a battlefield guide who is licensed and supervised by the Superintendent of the Park. Here they may also view the impressive Gettysburg Cyclorama which depicts a moment in the climax of Pickett's Charge and should inspire them to accept the Park's invitation to take its walking tour to the scene of the charge itself." [29] This site had the distinct advantage of permitting the study of the battlefield from its observation deck, surrounding paths, and walking tour. Mission 66 planners understood that, while park staff and Civil War enthusiasts might best imagine the events of the battle unfolding on a site free of modern intrusions, the average visitor looking out over the site saw ordinary fields dotted with curious statues. The purpose of Mission 66 was to benefit millions of anticipated visitors, and to this end the visitor center would bring life to the historic landscape.

|

History | Links to the Past | National Park Service | Search | Contact |

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/allaback/vc3b.htm

![]()