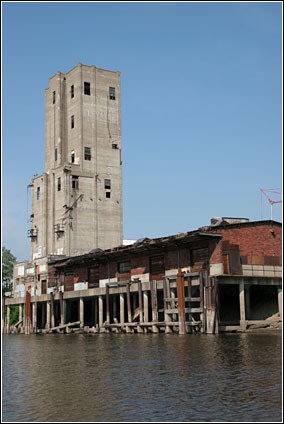

NPS IntroductionNote: In the summer of 2009, the St. Paul Municipal Elevator and Sackhouse was remodeled and renamed the "City House." It is now used as a municipal gathering place, a place to rest on the Mississippi River Trail. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder. This cliche is a great statement about how context, or frame of reference, informs our sense of what is beautiful and what is not, what is meaningful and what is irrelevant. Without context, the St. Paul Municipal Elevator and Sackhouse are eyesores, broken-down hulks, needless relics in a landscape being rejuvenated. But steep yourself in their river heritage, and you have to look at them anew. They will never be high architecture. These are blue-collar, rolled-up shirt-sleeve places. We have to appreciate them for what they are. The elevator (headhouse) and sackhouse possess local, regional and national significance. They can teach visitors and residents alike about debates over the shipping and marketing of the region’s grain, about inter-city rivalries, about Minnesota’s rural and urban past and about transforming the Mississippi River from a natural stream into a commercial highway. They are remnants–rare remnants–of St. Paul’s, port-city history. They are nationally significant as the remaining elements of a grain elevator complex that grew from the first successful grain terminal elevator owned and operated by a farm cooperative in America. They are locally and regionally significant as reminders of an effort by farmers to gain control of the marketing of their crops and the drive to reestablish the upper Mississippi River as a viable commercial artery. Grain MarketingDuring the late nineteenth century, Minnesota’s cereal production boomed, its flour milling grew to lead the nation, and railroads established the means to market huge quantities of grain nationally and internationally. In this context, some entrepreneurs saw the opportunity to control grain buying, selling and shipping. Two men dominated by the start of the twentieth century: William Wallace Cargill and Frank Hutchinson Peavey. They both located in Minneapolis in 1884 and helped build the city into one of the world’s major grain marketing centers. Cargill established a warehouse and offices in Minneapolis, and Peavey moved his headquarters to Minneapolis after the Minneapolis Millers Association became his largest buyer. Both became members of the Minneapolis Chamber of Commerce. Joined by the powerful flour millers and other grain merchants, Peavey and Cargill helped the Minneapolis Chamber corner cereal trading in the Midwest. In response, farmers began to protest. Started in Minneapolis in 1908 and incorporated under the laws of North Dakota in 1911, the Equity Cooperative Exchange emerged as one of several farm organizations to challenge the grain traders. The Equity initially focused on the fair marketing of spring wheat, taking on the Minneapolis Chamber of Commerce. The Equity and other critics accused the Chamber of rigging its prices and commissions against farmers. Farmers had little choice but to go through Minneapolis. The Federal Trade Commission estimated that 70 percent of the region’s cereal harvest between 1912 and 1917 passed through the city. As the Equity’s popularity among farmers grew, the Chamber fought back. In October 1912, the Chamber refused to allow its members to trade with groups or individuals that criticized the Chamber–a not so indirect threat against the Equity. This only made the farmers more determined to establish their own exchange, which they did in 1914, locating in Minneapolis. Connecting to the RiverThe Equity’s desire to run its own terminal and to increase farm profits meshed well with a navigation improvement effort underway on the upper Mississippi River. In 1907, the Upper Mississippi River Improvement Association convinced Congress to authorize a 6-foot channel. Under this project, the Corps of Engineers was to create a continuous channel, at least six feet deep at low water, using wing dams and closing dams. Long piers of rock and brush, wing dams projected into the navigation channel to narrow or constrict it. Like the nozzle on a garden hose, the wing dams quickened the river’s flow, allowing it to cut through sandbars. Closing dams, also made of rock and brush, shut off side channels to divert the river’s flow into the main stream. Although Congress had authorized the 6-foot channel, it questioned funding the project for two reasons. First, unable to compete with railroads, commercial traffic on the upper river had steadily declined. Second, few river cities had modern barge terminals. If port cities would not commit local funds to building modern terminals, Congress debated whether it should spend federal dollars on the 6-foot channel. To demonstrate its sincerity to Congress and to encourage river traffic, the Upper Mississippi River Improvement Association initiated a campaign to modernize river terminals. The Equity Cooperative joined this effort. Not only did the Equity establish its own exchange in 1914, it moved from Minneapolis to St. Paul. St. Paul promised the Equity free land along the upper levee, so the exchange could build a terminal grain elevator. The location provided access to rail lines and the river. The Equity broke ground in 1915 and completed the new building in 1917. At the dedication ceremony, J. M. Anderson, the Equity’s President, baptized the building with river water, hoping that the Mississippi would again become a factor in grain shipping. The Minneapolis Chamber rejected the idea that St. Paul could establish a grain exchange and terminal facilities. In 1917 the Chamber asserted that it was “utterly ridiculous” that “this milling industry, linseed oil industry and terminal elevator industry, can be transported to St. Paul by the establishment of a small pretended grain exchange or selling agency. . . ." The rivalry between St. Paul and Minneapolis had been long and bitter. Minneapolis envied St. Paul’s title to the head of navigation, and St. Paul coveted the hydropower at St. Anthony Falls and the grain trade it drew. When St. Paul persuaded the Equity to leave Minneapolis, the rivalry between the Equity and the Minneapolis Chamber of Commerce fed into this inter-city rivalry. The Equity’s timing was poor. Despite all the Corps’ work on the 6-foot channel projects, commerce continued leaving the river. As the Equity finished its elevator, through commerce on the upper Mississippi died. No steamboats carried or pushed cargo from St. Paul to St. Louis. Steamboats generally traveled less than 15 miles between their origin and destination. Their cargoes most often included rock and brush for channel improvement work under the 6-foot channel project. Even if some boats had made the trip to St. Louis, the Equity’s new elevator was not connected to the river yet. The Transportation CrisisAs the region’s need for a diverse transportation system had grown, its shipping options had declined, creating a transportation crisis. Railroad car shortages, the Panama Canal’s opening in 1914 and several Interstate Commerce Commission decisions combined with channel constriction’s failure to erect, Midwesterners declared, an “economic barrier” around their region. Although the Engineers had built thousands of wing dams and had closed many of the river’s side channels, they had been unable to create a dependable navigation channel. All too frequently, droughts and floods made the channel impassable. Rail car shortages, occurring in 1906-07, during World War I, and in 1921, caused acute, short-term shipping crises, and pointed out the Midwest’s dependence on railroads.

The Panama Canal's opening in 1914 redefined the Midwest's transportation problems. While railroad car shortages had been infrequent, the Panama Canal created a problem that promised to become steadily worse. Economically, the Panama Canal moved the East and West coasts closer to each other while moving the Midwest farther away from both coasts. Businesses could ship goods from New York to San Francisco through the Panama Canal cheaper than Midwesterners could ship goods to either coast by rail. The transportation crisis climaxed with the Interstate Commerce Commission's decision in the Indiana Rate Case of 1922 and the subsequent decisions that upheld it. On October 22, 1921, the Public Service Commission of Indiana and others challenged the Midwest's railroad rate structure. For unfair reasons, they argued, railroads operating out of Illinois and cities along the west bank of the Mississippi River in Missouri and Iowa charged lower rates than railroads running out of Indiana. Railroads running along the river charged lower rates because a 1909 decision by the Commission had upheld the lower rates based upon the potential and reality of waterway competition. In the Indiana Rate Case, the Commission reversed its earlier decision. Now, it stated, "Water competition on the Mississippi River north of St. Louis is no longer recognized as a controlling force but is little more than potential." In effect, the commission declared the Midwest landlocked. On February 14, 1922, the Commission ordered railroads operating along the river to raise their rates, leading to a 100 percent or greater rise in some Midwestern shipping rates. Appeals by the defendants and waterway advocates delayed the decision's implementation until June 1, 1925. High shipping costs especially worried farmers. During the 1920s, they entered a depression that would last into the Great Depression of the 1930s. Without the Mississippi as a viable competitor to railroads, they feared monopolistic rates. To farmers, cheap transportation meant the difference between surviving and bankruptcy. In this climate, Cooperatives, like the Equity, and the river became even more important to farmers and the Midwest's economy. In response to the growing transportation crisis, navigation boosters initiated another movement to revive river shipping, a movement that surpassed all previous movements. Between 1925 and 1930, they fought to restore commerce and persuade Congress to authorize a new project for the river, one that would allow the Mississippi to truly compete with railroads. It would draw support from the largest and smallest businesses in the valley, from most of its cities, from the Midwest's principal farm organizations, and from the major political parties. St. Paul and Minneapolis pushed especially hard. As largest cities above St. Louis, they, more than any other cities, would have to convince Congress to approve a new project. Municipal Elevator and SackhouseIn 1923 George C. Lambert became the secretary-treasurer and general counsel of the Minnesota Farmers Union, which took over the Equity Cooperative Exchange that year. Lambert believed that the success of this terminal and the Farmers Union depended upon the success of river transportation. Likewise, he realized, Congress would watch the river's cities to judge their commitment to any new, big navigation project. So, Lambert joined the movement. In 1927 he helped convince St. Paul to expand the Minnesota Farmers Union Elevator, as part of City's effort to encourage navigation. St. Paul approved a new addition that included a 22,000-bushel, reinforced-concrete elevator or headhouse, a clay-tile sackhouse and a loading dock. Conveyors connected the headhouse to the old Equity Elevator and the sackhouse to a flour mill across the road. Now farmers had a direct and modern facility for delivering their grain to the Mississippi. All they needed was a river capable of handing large, fully-loaded barges. St. Paul and the Minnesota Farmers Union hoped Congress would view the new elevator complex as evidence that a major new project for the upper Mississippi River was justified. Responding St. Paul and to the broader navigation improvement movement, Congress included the 9-foot channel project in the 1930 Rivers and Harbors Act. The project called for 23 locks and dams from just above Red Wing, Minnesota, to Alton, Illinois. When completed in 1940, the locks and dams created a series of deep reservoirs that could guarantee a navigable channel, even during droughts. Although traffic returned slowly to the river, by the late 1950s the Minnesota Farmers Union Elevator complex had become the key transfer point for grain going from rail car to barge. In 1938, 121 cooperatives from Minnesota, the Dakotas and Montana, including the Farmers' Union, formed the Grain Terminal Association or GTA. Over the next two decades, GTA expanded the facility to take advantage of the new navigation system. By the 1950s, farm cooperatives were an accepted part of Minnesota and regional agriculture. As one scholar wrote, "the radicalism of 1916 is in large measure the accepted practice of today." A Special PlaceSo, while they may not be pretty, the St. Paul Municipal Elevator and Sackhouse represent important local, regional and national stories. They tell us about:

Today the elevator and sackhouse are the only remaining structures on St. Paul's riverfront associated with the above stories. They are the only structures left on either the Upper or Lower Levee that tie the city to its port city heritage. A Sense of PlaceFor some, knowing the history of the St. Paul Municipal Elevator and Sackhouse, may be enough for them to see its beauty and relevance. Others may not yet make the connection between this place, its history and their world. My worry that not everyone appreciates their importance is partially ameliorated by the fact that people and communities have a strong, inherent need for special places. James Howard Kunstler, in an Atlantic Monthly article entitled "Home from Nowhere," says that "Americans sense that something is wrong with places where we live and work and go about our daily business. We hear this unhappiness," he observes, "expressed in phrases like 'no sense of place' and 'the loss of community.'" To lose the Municipal Elevator and Sackhouse would contribute to both a loss of community and a loss of sense of place, not just for the Upper Levee, the neighborhoods around it and the City of St. Paul but for a much broader region. Sense of place happens in specific places. "Indeed events and actions are significant only in the context of certain places, and are coloured and influenced by the character of those places even as they contribute to that character," stresses Edward Relph in his book Place and Placelessness. Real places, places you can see and touch and experience act "as authentic witness to the past, these places provide assurance that these stories are not make-believe, but involve real people facing real-life situations and issues." Authenticity and sense of place flow from the Municipal Elevator and Sackhouse. Places connect people to the past in a way that markers and exhibits cannot. "The result of such a growing attachment, imbued as it is with a sense of continuity," Relph insists, "is the feeling, that this place has endured and will persist as a distinctive entity even though the world around may change." The world around the elevator and sackhouse have changed many times and are changing again. The elevator and sackhouse provide testimony to that change but also to a continuity with the past that no other structures can. Kunstler says it more poetically. "Chronological connectivity lends meaning and dignity to our . . . lives. It charges the present with a vivid validation of our own aliveness. It puts us in touch with the ages and with the eternities, suggesting that we are part of a larger and more significant organism.... In short, chronological connectivity puts us in touch with the holy. It is at once humbling and exhilarating. ... Connection with the past and the future is a pathway that charms us in the direction of sanity and grace." Places anchor individuals and communities to their heritage. They evoke a sense of pride in and belonging to something special and meaningful. Their power to do this comes from their authenticity, their real, physical connection to the past. If cities have a spirit or soul, St. Paul's is surely felt strongest near the river and in places, such as the Municipal Elevator and Sackhouse, that are carried along in the current of the river's history. Contact: John Anfinson (Superintendent) 651-293-0200 |

Last updated: November 22, 2019