Last updated: December 5, 2025

Article

Christina Cantine

Faith, Family, and Principle in the Shadow of Power

Born on November 4, 1802, Christina Maria Cynthia Cantine was raised at the crossroads of two worlds: the genteel but fading Dutch culture of early New York and the rising political power centered in Albany and Washington. As the niece of Hannah Hoes Van Buren and by marriage the niece of President Martin Van Buren, Christina’s life unfolded in close proximity to the heart of national influence. Yet she chose a different path—one rooted in spiritual conviction, moral reform, and a deep ambivalence toward public life.

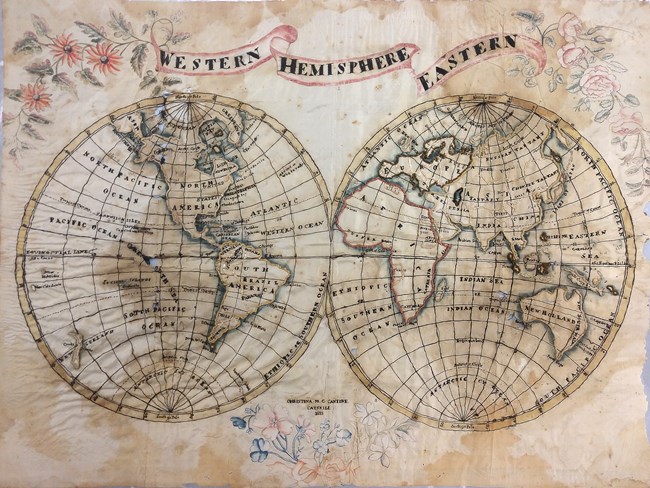

Christina’s early years in Catskill, New York, reflected her family’s prominence. Her father, Moses I. Cantine, was a War of 1812 veteran, lawyer, New York state senator, and newspaper editor for the Albany Argus. Christina was educated at the Catskill Academy, where she created a map sampler in 1813—an emblem of both classical education and traditional feminine accomplishment. Intellectually curious and morally driven, she engaged deeply with religion, politics, and social causes throughout her life.

In 1823, both of Christina’s parents died, leaving her, at 21, to navigate adulthood through grief and faith. She became administrator of her mother’s estate in 1825 and spent the following years traveling among relatives in Kinderhook, Albany, Ithaca, Catskill, and Kingston.

Her letters from this time are filled with spiritual yearning and emotional depth. In a poignant 1824 letter, she wrote of her Uncle John:

“Uncle John who resembled my dear Father in his looks, but more infinitely more in his actions and conversation. This though it endears him to me the more, makes me feel deeply, sometimes even agonizingly my loss. I have not looked at him for hours particularly in the evening, when he always reads, till I have almost fancied it was my own dear Parent.”

Christina’s personal sorrow propelled her further into religious devotion. In 1828, she joined the First Presbyterian Church in Ithaca, where she became active in revivals and benevolent work.

A Principled Refusal of Political Society

Despite receiving repeated invitations to live with Martin Van Buren—first in Albany and later in Washington—Christina declined. She feared that elite social life would compromise her values. In a letter to her friend Caroline Frey, she pondered:

“"I would cheerfully make a sacrifice of my own feeling for his [Van Buren's] gratification if I thought I could do it consistently – but do you not think, my friend, that I would be putting myself in the way of temptation by going to Albany – & could I go there & then with confidence pray 'lead me not into temptation'"

She expanded on this conflict when declining Van Buren’s request that she reside with him during his vice presidency:

“Uncle V.B. had been trying to prevail on me to stay & make it my home with him…. I could not consent to live as he would with to have me—he would expect me to do many things that would be repugnant to my feelings & my principles.”

Her refusal was not only an act of personal conscience but also a subtle protest against the performative expectations placed on women in political households.

A Woman of Reform and Reflection

Christina’s moral convictions extended into active engagement with reform movements. In 1828, shortly after New York's final emancipation law took effect, she helped organize and teach at a Sunday school for Black children and adults in Kinderhook. Although her language reflected the paternalism of her time, her actions reveal a possible sincere desire to offer education and support.

She was also an outspoken critic of slavery and its political enablers. In an 1837 letter, she expressed deep disappointment with her uncle’s inaugural address:

“When I took up the paper to read his address my eye happened to light on that obnoxious paragraph in relation to slavery—and I at once laid it aside—sick at my very heart.”

Christina didn't always rely on well written letters to let her feelings known either. Martin Van Buren recorded an incident in his autobiography where Christina confronted him over his treatment of Native Americans and his support of the Indian Removal Act of 1830. Van Buren quoted her scolding:

"Uncle! I must say to you that it is my earnest wish that you may lose the election, as I believe that such a result ought to follow such acts!"

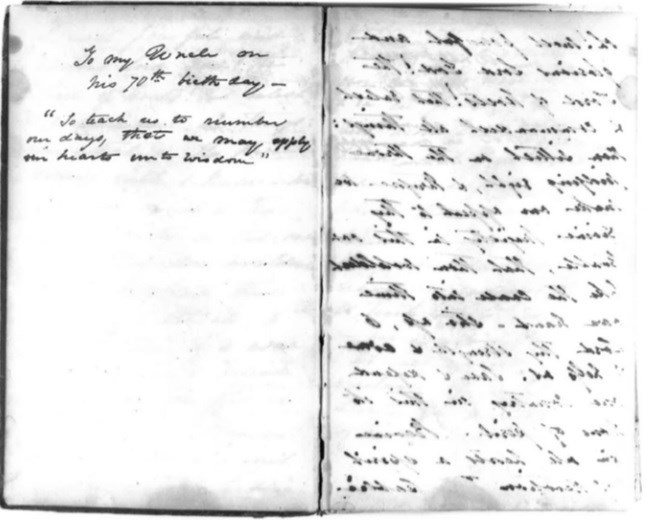

Yet she never gave up hope for Van Buren’s spiritual awakening. In the 1850s, she redoubled her efforts to steer him toward a life of faith. On his 70th birthday in 1852, she presented him with a Bible inscribed with personalized prayers, invoking both national and spiritual urgency:

"To my Uncle on his 70th birthday, 'To teach us to number our days, that we may apply our hearts unto wisdom'"

Van Buren acknowledged her influence in a letter to his friend Mrs. Enos Throop:

“Between you and my niece my chances of becoming a good man are not as desperate as I feared they were.”

By his retirement, he had grown accustomed to finding the Bible open and ready for morning devotions—often turned to specific passages she had selected during her extended stays at Lindenwald. Christina believed that God might still use Van Buren for good and documented how strangers were praying for his conversion.

A Quiet Legacy

Though she never married, Christina found lifelong companionship in her friendship with Caroline Frey and remained close to her extended family. In her later years, she contributed a moving remembrance of her aunt Hannah Van Buren to Laura Holloway's The Ladies of the White House, preserving a rare and intimate glimpse into the Van Buren family at the request of Angelica Singleton Van Buren.

She supported missionary and moral causes throughout her life, donating generously and ultimately leaving her estate to the American Tract Society and the American Bible Society.

Christina Cantine died in Ithaca on August 20, 1883. Her headstone bears a line from the hymn “Rock of Ages”:

“LOOKING UNTO JESUS / IN MY HAND NO PRICE I BRING / SIMPLY TO THY CROSS I CLING.

Christina Cantine lived at the edge of power but refused to be consumed by it. Her life was one of spiritual intensity, principled independence, and enduring familial love. In her letters, we glimpse a woman wrestling with duty, conscience, and faith—a voice of resistance grounded not in ambition, but in conviction. Through her quiet legacy, Christina reminds us that moral clarity often emerges most powerfully in the margins of history.