|

Introduction

This historic summer camp comprises 63 acres of rolling woodland along the Little Calumet River. It is the only summer camp built by the U.S. Steel Company for its employees' children. U.S. Steel's Gary Works Good Fellow Club operated the camp with its nine historic buildings from 1941 to 1976. The National Park Service purchased the camp in 1976 for inclusion within the Indiana Dunes National Park. Today it is the site of the Dunes Learning Center.

The steel industry has long shaped the social, economic, cultural, and physical landscape of Northwest Indiana. U.S. Steel began in the area in 1906 and soon led the industry in establishing employee benefit programs to avert strikes, stabilize its work, and to attract and retain skilled labor. Along with Gary Works, once the country's largest steel plant, U.S. Steel built housing, schools, parks, and playgrounds in the City of Gary. The company funded local churches and community organizations, such as the Young Men's Christian Association, and launched company-sponsored health clinics. U.S. Steel's Good Fellow Club was born of "enlightened" ideas on labor management. In the Depression, years many U.S. Steel plant managers founded Good Fellow Clubs to help needy members cope with hardship. From 1914 to 1921, the Gary Works club focused on Christmas and welfare activities. In 1916, the club held a Christmas party at the Broadway Theater for 1,500 employees' children and handed out hundreds of Christmas baskets to the poor. That same year the club helped 269 disadvantaged employees, providing groceries, milk, fuel, and medical aid. The club sponsored bi-weekly infant health clinics and offered educational classes in such subjects as English language. A casualty of the 1919 steel strike, the Good Fellow Club's programs were continued (after 1921) under the auspices of the Illinois Steel Welfare Association. In 1938, the Gary Works' superintendent revived the club as a local entity when plant foremen lobbied for a social club. The reorganized Good Fellow Club, which still exists today, emphasized employee recreation over welfare needs. The club offered basketball, baseball, football, bowling, horseshoes, ping-pong, archery, golf, horseback riding, trap shooting, rod and gun clubs, and a travel club.

NPS image collection From this context of industrial relations came the idea of a youth camp. The Good Fellow Club Youth Camp of the Gary Works operated from 1941 to 1976. The camp, a short train ride from Gary, enabled workers' children to enjoy the environmental benefits of healthful recreational activities in the forest near Lake Michigan. The camp accommodated 60 to 100 children, ages eight to fifteen. Children came for one-week segments which ran for eight weeks of each summer.

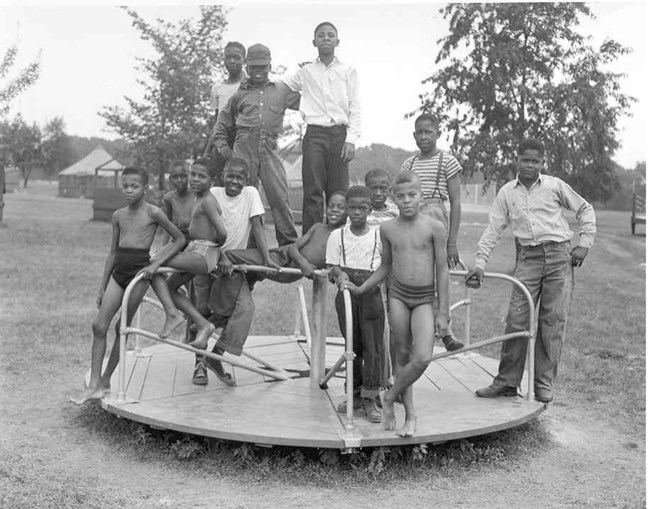

NPS image collection Wartime labor and material shortages slowed expansion of the camp until 1946 when new additions included a stainless steel swimming pool, a combination water filtration plant and pool house, four concrete tennis courts, three shuffleboard courts, and a playground with swings, sliding boards, horizontal boards, and a merry-go-round. The camp also boasted an archery range, horseshoe area, croquet lawns, and basketball and badminton courts. The Gary Post Tribune touted the expanded summer camp as, "one of the best equipped youth outing centers this side of the Adirondacks." Until 1951, campers and counselors slept in canvas tents. "When the wind blew and the rain fell you felt like a real pioneer," said Vernon Charlson, camp director, 1943 to 1957. The camp generated positive public image for U.S. Steel in Northwest Indiana. Newspapers reported the camp's nominal 1945 fee of $4 per week for employees' children and the offer of scholarships to disadvantaged children. In 1946, the 30 by 60 feet all-steel pool was unveiled. Aware of the advertising opportunity, U.S. Steel executives from Pittsburgh traveled to Gary to dedicate the pool. In later years, company visitors from as far away as Russia and Japan, viewed the amenities of the camp and admired the merits of steel construction. During its 34 year history, the camp fostered excellent relations between U.S. Steel and surrounding communities. Particularly during the early 1950's, the camp was available for meetings of local organizations such as Gary Kiwanis Club, Chesterton Lions Club, Lake County Credit Union, Chicago Motor Club Boys' Patrol, and the Gary University Club. The National Park Service purchased the property in 1976 and it became part of the Indiana Dunes National Park. The Good Fellow Club Youth Camp is now the site of the Dunes Learning Center.

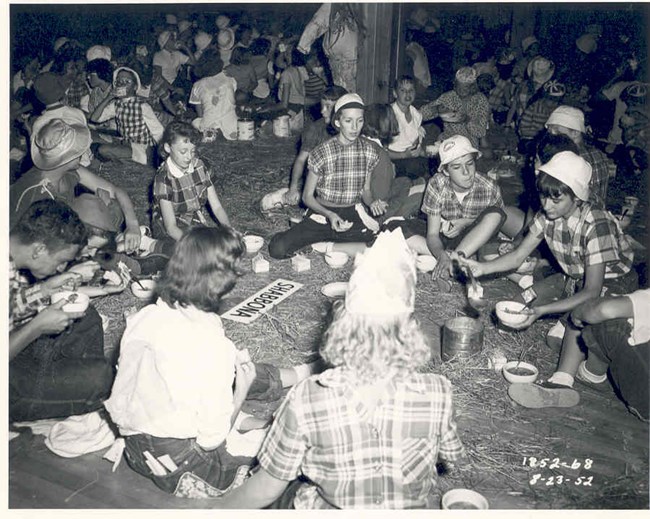

NPS image collection Besides demonstrating industry's impact on Northwest Indiana, the camp offers insight into the social history of the 1940s and 1950s. To its campers, a session was more than a week of recreation in the woods. Camp staff and club sponsors wanted campers to learn values of sportsmanship, democratic living, proper etiquette, outdoor appreciation, and spirituality during their week at camp. The staff capitalized on the setting in the Baillytown area to emphasize "the atmosphere of friendship that existed between the early American pioneers and Indians." The "Indian Appreciation Program" stressed Native American lore, nature study, local history, and handicrafts. From opening day pow-wow to cabins named Potawatomi, Waubansee, Pontiac, Chekagou, and Shabbona, the camp employed Native American symbols to bond campers in a spirit of cooperation. On a typical day in 1943 Counselor Hawkinson dressed himself as "Red-Tailed Hawk." Campers boated on the Little Calumet River as he spoke of local Native American tribes, duneland natural history, and the history of the Bailly Homestead. At each week's closing ceremony campers gathered at "The Bailly Marriage Tree," an intertwined oak and elm commemorating the marriage of Joseph Bailly's daughter Rose and Francis Howe. Campers floated boats down the Little Calumet River, with lighted candles representing the spirit of Good Fellow, and recounted what camp meant to them. Staff used Native American lore to unite children from steel executive's families to children of laborers'. The campers were expected to forget their differences.

NPS image collection The camp also expressed social values of the time. The camp proved a microcosm of Northwest Indiana; a region segregated before, during, and especially after World War I. Job opportunities in steel drew large numbers of African Americans from the south. By 1910, more than half of Gary's 17,000 residents were either African American or foreign-born. In the 1940s, six weeks of the eight-week summer program were reserved for "white" children, leaving two weeks for African Americans. Camp staff and the Good Fellow Club kept records for racial groups. A 1943 Committee Report noted 312 white campers gained an average of two pounds on camp cuisine while 91 "colored" children gained an average of four pounds, four ounces. Connection to Entertainment and Recreation With use of natural materials and local craftsmanship, the camp retains the historic feeling associated with the rustic architecture popular for camps in the 1930s and 1940s. These styles were derived from the country's first leisure camps built in the Adirondack Mountains for the social elite. The Adirondack camps, constructed from the Civil War to the Great Depression, expressed the American infatuation with wilderness as the country grew more tame. Characterized by giant, peeled logs for structure and design and massive fieldstone chimneys and foundations, the National Park Service so admired the way the camps blended with their surroundings that it adapted a similar design for buildings at Yellowstone and Glacier National Parks. Later, the Civilian Conservation Corps and other government agencies employed simpler versions of these designs for park recreational structures. By 1940, the use of rustic motifs grew popular for roadside camps and filling stations. "The reason for this interest in the rustic design is that when people leave the city or towns where they live, they want a change," reported in American Builder in July 1940.

NPS image collection The Good Fellow Club Youth Camp exemplifies the outdoor recreational experience that U.S. Steel wanted to provide and convey. The main lodge's cedar interior appears much as it did when campers gathered in its 59' by 30' dining hall. Here each cabin of ten campers ate at dining tables with cross-buck supports. Campers gathered before a massive stone fireplace for talent shows, sing-a-longs, movie nights, Sunday open houses and lectures. With a distinctive blend of steel and natural materials, the camp offered rustic architecture and the illusion of wilderness living. Year-round caretaker Wallace Ahrendt kept the paneling varnished and gleaming. He cultivated 2,000 scotch and white pines to complement the stone entrance and the grounds' natural look. Hand-made log furniture on the lodge's porch further added to the ambiance of roughing-it in style. For U.S. Steel executives who used the camp for meetings, the lodge became a nearby retreat, yet far away from the smoke of the Gary Works. For many campers a visit meant their first taste of country living and vacations. The Good Fellow Club Youth Camp offers tangible evidence of U.S. Steel's concept of a major recreational development as a suitable benefit for its employees' children. |

Last updated: February 4, 2022