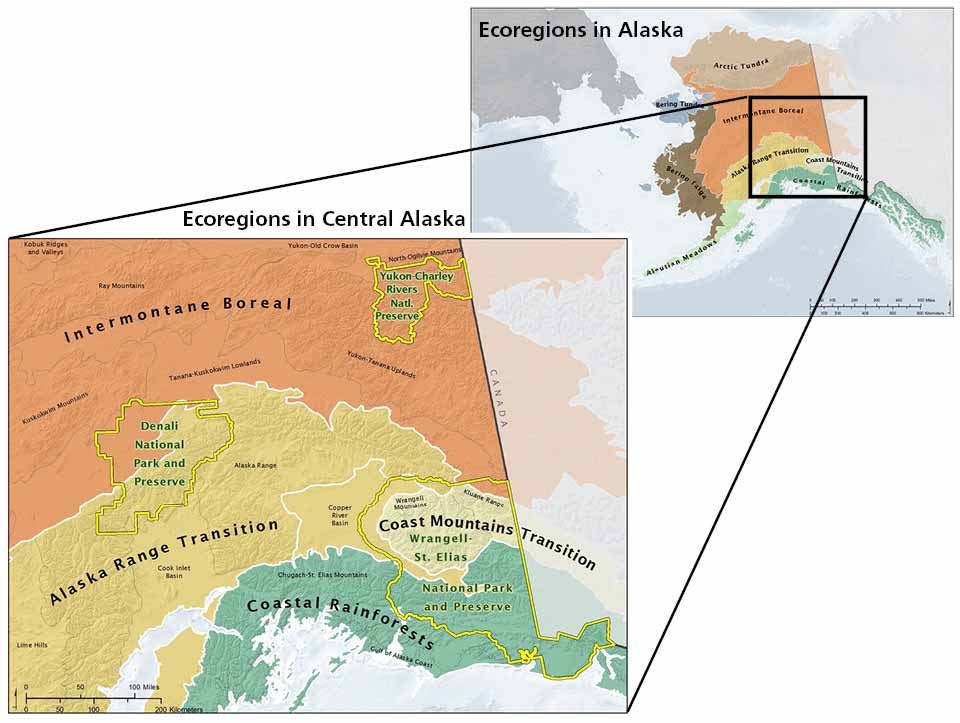

The Central Alaska Network spans a wide latitudinal gradient that ranges from 120 miles of coastline in Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve northward across two mountain ranges (the Chugach and Alaska ranges) and into the boreal forest of interior Alaska. The above ecoregion map illustrates the ecosystems found in Central Alaska Network parks; each is described below.

Coastal Rainforests

Beginning at the southernmost portion of the network, the coastal areas adjacent to the North Pacific Ocean receive copious amounts of precipitation throughout the year. The temperature does not vary greatly because of the nearby ocean. This steady temperature means that trees grow abundantly and dominate at lower elevations.

NPS/Brian Petryl

Chugach-St Elias Mountains

In the mountains, massive ice fields and glaciers are common. The alpine plant communities of sedges, grasses, and low shrubs support Dall’s sheep, mountain goats, hoary marmots, pikas, and ptarmigan. Where glaciers and icefields have receded, broad U-shaped valleys are left, many with sinuous lakes. In these areas alder shrublands and mixed forests grow on lower slopes and valley floors where moose and brown and black bears forage. Lush, lichen-draped temperate rain forests of hemlock and spruce interspersed with open wetlands blanket the shorelines and adjacent mountain slopes along the Gulf of Alaska. Bald Eagles, Common Murres, Bonaparte’s Gulls, Steller’s sea lions, harbor seals, and sea otters team along its endless shorelines. Numerous streams and rivers support Dolly Varden, steelhead trout, and all five species of Pacific salmon. Salmon spawning runs deliver tremendous amounts of nutrients to aquatic and terrestrial systems. Rare dusky Canada Geese and Trumpeter Swans nest on these wet flats where brown bears, Sitka black-tailed deer, and moose roam.

Coast Mountains

The high mountains on the interior side of the coastal mountains are exposed to a peculiar mix of climates. Because of their sheer height, these mountains capture ocean-derived moisture as it passes inland. Yet, due to their proximity to the interior, they possess a fair degree of seasonal temperature change similar to a continental climate. Climatic influences change with elevation, with maritime conditions on mountaintops (feeding ice caps and glaciers) grading to continental conditions at their base (boreal forests).

Wrangell Mountains

The Wrangell Mountains are a volcanic cluster of towering, ice-clad mountains at the northwest edge of the St. Elias Mountains. Shrublands of willow and alder with scattered spruce woodlands ring the lower slopes. Spruce and cottonwood grow along larger drainages. The Wrangell Mountains are highly dynamic due to active volcanism, avalanches, landslides, glaciers, and stream erosion. Soils are thin and stony and underlain by discontinuous permafrost. Its best-known denizen, Dall’s sheep, roams throughout the area along with mountain goats, brown bears, caribou, wolverines, and gray wolves.

Alaska Range Transition

Boreal forests occur within the basins and troughs fringed by the Alaska Range. This area is considered transitional since some climatic moderation is afforded by the nearby Pacific Ocean (i.e., maritime moisture). Ice sheets heavily scoured this area during the last glaciation, and small ice caps and glaciers still exist at high elevations.

NPS/Jacob Frank

Alaska Range

Because of the Alaska Range’s height, a cold continental climate prevails, and much of the area is barren of vegetation. At the termini of glaciers, swift glacial streams with heavy sediment loads course down mountain ravines and braid across valley bottoms. Alpine tundra supports populations of Dall’s sheep and pikas on mid and upper slopes. Shrub communities of willow, birch, and alder occupy lower slopes and valley bottoms. Forests are rare and relegated to the low-elevation drainages. Brown bears, gray wolves, caribou, Dall’s sheep, and wolverines are common denizens in the Alaska Range.

NPS/Jacob Frank

Cook Inlet Basin

The Cook Inlet Basin includes numerous lakes, ponds, and wetlands that attract large numbers of waterfowl (including Trumpeter Swans) and shorebirds. Dolly Varden and whitefish occur in freshwaters. Several river systems support recovering salmon runs and resultant bear and raven populations. Mixed forests of white and Sitka spruce, aspen, and birch grow on better-drained sites and grade into tall shrub communities of willow and alder on slopes along the periphery of the basin. A mixture of wetland habitats supports numerous moose, black bears, beavers, and muskrats.

NPS/Shea Combs

Copper River Basin

The Copper River Basin is a large wetland complex underlain by thin to moderately thick permafrost and pockmarked with thaw lakes and ponds. A mix of low shrubs and black spruce forests and woodlands grows in the wet organic soils. Cottonwood, willow, and alder line rivers and streams as they braid or meander across the basin. Spring floods are common along drainages. Arctic grayling, burbot, and anadromous sockeye salmon are common fishes. Black and brown bears, caribou, wolverines, and ruffed grouse are present throughout these wetland habitats.

Intermontane Boreal

Boreal woodlands and forests are characterized by extreme seasonal temperature changes from long, cold winters to short, moderately warm summers. The interior climate is fairly dry throughout the year and forest fires rage through summer droughts.

NPS/Kent Miller

Tanana-Kuskokwim Lowlands

The Tanana-Kuskokwim Lowlands are a plain of loosely aggregated soil that slope gently northward from the Alaska Range. Sand dune fields and glacial moraines occur in some areas. Collapse-scar bogs and fens caused by retreating permafrost are frequent and related to climate warming since the Little Ice Age. Streams flowing across this north-sloping plain ultimately drain into one of two large river systems—the Tanana or Kuskokwim. The mosaic of habitats supports moose, black bears, beavers, porcupines, trumpeter swans, and numerous other waterfowl.

NPS/Ken Hill

Yukon-Tanana Uplands

The broad, rounded mountains of the Yukon-Tanana Uplands are underlain by former volcanic island arcs and continental shelf deposits. In valley bottoms, permafrost is thin, ice-rich, and relatively “warm.” Vegetation is dominated by white spruce, birch, and aspen on south-facing slopes, black spruce on north-facing slopes, and black spruce woodlands and tussock and scrub bogs in valley bottoms. Floodplains of headwater streams support white spruce, balsam poplar, alder, and willows. Above treeline, low birch-heather shrubs and Dryas-lichen tundra dominate. This area has the highest incidence of lightning strikes in Alaska and the Yukon Territory, causing frequent forest fires. Caribou, moose, snowshoe hares, marten, lynx, and black and brown bears are plentiful. The area’s abundant cliffs are important to Peregrine Falcons. The clear headwater streams are important spawning areas for chinook, chum, and coho salmon.

NPS/DevDharm Khalsa

Yukon River

Opaque with glacial silts and shoreline mud, the Yukon River forms an aquatic maze of islands, sandbars, meander sloughs, and oxbow lakes as it crisscrosses the lower flats. The rich aquatic habitats support tremendous concentrations of nesting waterfowl (in the millions) and other migratory birds and an abundance of moose, bears, furbearers, northern pike, and salmon.

NPS/Kyle Joly

North Ogilvie Mountains

The North Ogilvie Mountains have the characteristics of an unglaciated area that has undergone long periods of erosion. Shallow soils have developed in rocky areas on mountainsides where landslides, debris flows, and soil creep frequently occur. On lower slopes, soils are deeper, more moist, and underlain by extensive permafrost. Low shrub tundra of willow, alder, and birch and aspen and spruce woodlands occur at lower elevations. These mountains are the source of many streams that eventually feed the Porcupine, Yukon, and Peel Rivers. Lakes are relatively rare. Brown bears, wolverine, Dall’s sheep, caribou, lemmings, and pikas are common inhabitants of these mountains.

Yukon-Old Crow Basin

Finally, the farthest north ecoregion is the Yukon-Old Crow Basin. It is a gently sloping basin along the Porcupine River comprised of depositional fans, terraces, sediments, and mountain toeslopes that ring the Yukon and Old Crow Flats. The poorly drained flats and terraces harbor vast wetlands pockmarked with dense concentrations of thaw lakes and ponds.

Last updated: April 9, 2018