Credit: Frontiers for Young Minds

How do we know if parks are healthy? We measure their vital signs, of course! Across the country, there are 32 inventory and monitoring networks that measure the status and trends of all kinds of park resources. We're learning a lot after years of collecting data.

These articles are a part of a collection, or special issue, of Frontiers for Young Minds, an international online journal of science written for kids and involving kids in the review process. Taking the Pulse of U.S. National Parks presents what we are learning from years of monitoring plants and animals and physical conditions in parks. The articles featured here are results from Arctic parks.

Credit: Frontiers for Young Minds

Permafrost and Draining Lakes in Arctic Alaska

In the Arctic, the ground is frozen most of the year. Only the top layer of soil thaws each summer. This frozen ground, called permafrost, contains a lot of frozen water (ice). There are many small lakes in the Arctic, in low spots formed from melted ice. But melting ice does not just create lakes, it can destroy them too. Melting permafrost can create gullies that let the water drain out of a lake. Most lakes in the Arctic are far from where people live, so we watch them using pictures taken from satellites. Recently, we have seen the water drain out of many lakes, which can affect plants and animals. We measure the number and size of drained lakes caused by thawing permafrost to understand how the Arctic is changing.

Also see: monitoring permafrost and lakes in the Arctic

Swanson, D. 2022. Permafrost and Draining Lakes in Arctic Alaska. Frontiers for Young Minds 10:692218. doi: 10.3389/frym.2022.692218

Credit: Frontiers for Young Minds

Beavers build dams that change the way water moves between streams, lakes, and the land. In Alaska, beavers are moving north from the forests into the Arctic tundra. When beavers build dams in the Arctic, they cause frozen soil, called permafrost, to thaw. Scientists are studying how beavers and the thawing of permafrost are impacting streams and rivers in Alaska’s national parks. For example, permafrost thaw from beavers can add harmful substances like mercury to streams. Mercury can be taken up by stream food webs, including fish, which then become unhealthy to eat. Permafrost thaw can also move carbon (from dead plants) to beaver ponds. When this carbon decomposes, it can be released from beaver ponds into the air as greenhouse gases, which cause Earth’s climate to warm. Scientists are trying to keep up with these busy beavers to better understand how they are changing Arctic landscapes and Earth’s climate.

Also see: monitoring streams and lakes in the Arctic

O’Donnell, J., M. Carey, B. Poulin, K. Tape, and J. Koch. 2022. How Beavers Are Changing Arctic Landscapes and Earth’s Climate. Front. Young Minds. 10:719051. doi: 10.3389/frym.2022.719051

Credit: Frontiers for Young Minds

Two degrees matters

How do you tell if someone is not well? You take the person’s temperature. If it is too warm, something is not quite right. We care about how the weather and climate are changing in Alaska’s national parks, so we continuously take their temperatures. We have dozens of weather stations in remote locations in the northern Alaska parks that run continuously, powered by the sun. Over the past several years, we found that the air and ground temperatures have been warmer than normal. Plants, animals, and people get used to living in their environments. They thrive within an expected temperature range. Things get out of whack when the environment that organisms are accustomed to changes. In northern Alaska, warming of just a few degrees can cause ice to melt and formerly frozen ground to thaw. Once the ground thaws, the ice changes to water and the landscape changes.

Also see: climate monitoring in the Arctic, permafrost monitoring in the Arctic, climate monitoring in Central Alaska, permafrost monitoring in Central Alaska, climate monitoring in Southwest Alaska, climate monitoring in Southeast Alaska, high-latitude climate change

Hey Teachers! Check out this lesson plan.

Sousanes, P., K. Hill, and D. Swanson. 2022. Two Degrees Matters. Frontiers for Young Minds 10:719108. doi: 10.3389/frym.2022.719108

Credit: Frontiers for Young Minds

What goes up must come down: The influence of climate on caribou populations

Wildlife populations naturally go up and down. Oscillation is the term used for this pattern of highs (when there are many animals) and lows (when there are few). When the number of births is greater than the number of deaths, then populations grow. If deaths exceed births, populations decline. Caribou in the Arctic have dramatic population oscillations. The number of caribou can grow very high and also decrease to very few. Large-scale, long-lasting weather oscillations are one reason for this pattern. Knowledge of the connection between wildlife populations and climate oscillations is important to help conserve species like caribou and to better understand how climate change will impact wildlife.

Also see: monitoring caribou in the Arctic and in Central Alaska

Hey Teachers! Check out this lesson plan.

Joly, K. 2021. What Goes Up Must Come Down: The Influence of Climate on Caribou Populations. Frontiers for Young Minds 9:631372. doi: 10.3389/frym.2021.631372

Credit: Frontiers for Young Minds

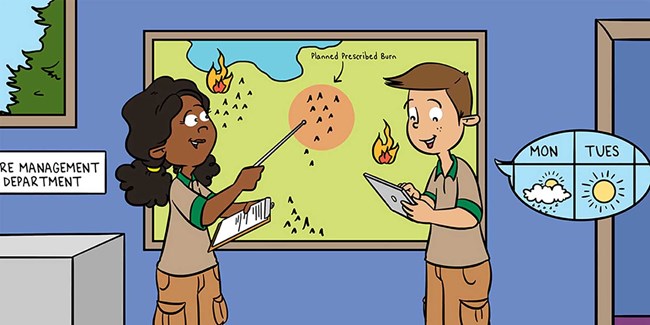

Rising from the Ashes: The role of fires in National Parks

Fire is a natural and healthy part of many ecosystems, and many plant species rely on it to reproduce. Some species require the actual heat and flames for their seeds to be released and sprout. Other species rely on fire to burn off dried needles and leaves on the ground as well as many of the shrubs and small trees. This opens up the forest and allows more space and light for small plants and trees. While fire is a good thing for many plants and ecosystems, this is not the case everywhere. In areas that get high amounts of rain, ecosystems are not adapted to fire. Human-caused fires in these places can be devastating to the plants there. It is the job of fire managers and ecologists to manage wildfires, make decisions about fire suppression, and decide if additional fires are needed in key ecosystems.

Also see: Fire extent and severity in the Arctic

Sanders, S., L. Mutch, M. Wasser, J. Barnes, and S. Perles. 2021. Rising From the Ashes: The Role of Fires in National Parks. Frontiers for Young Minds 9:627635. doi: 10.3389/frym.2021.627635

Last updated: December 8, 2025