NPS Photo A traditional hierarchy governed the furnace’s operations. At the pinnacle was the ironmaster, director of the enterprise and often an owner. Good ironmasters had to be financier, technician, bill collector, market analyst, personnel director, purchasing agent, and host to prospective buyers. His was a volatile job: bad luck or poor judgment usually meant failure. Success often brought wealth. A clerk helper kept the books, ordered supplies, served as paymaster, and managed the office store. The job well performed could be a stepping-stone to ironmaster.

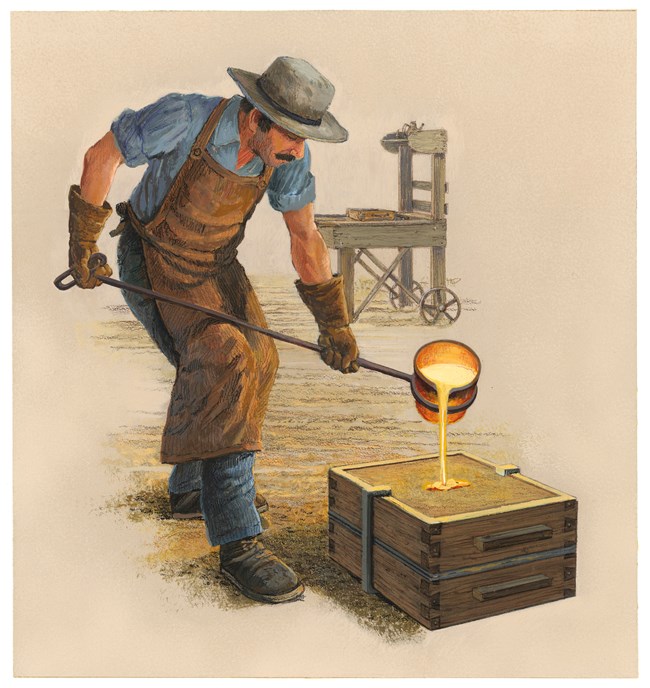

The quality of iron was in the founder’s hands. His job: keep the furnace blowing at peak efficiency. He supervised the other furnace workers: keepers helped him monitor the furnace and took the night shift; fillers charged the furnace with raw materials; and guttermen directed molten iron as it flowed from the furnace. Moulders, the highest-paid workers, had the exacting job of casting the iron. Colliers (charcoal makers), miners, and woodcutters provided the raw materials for the furnace. Other workers included teamsters, who drove the wagons carrying raw materials and finished products; cleaners, often women and children, who finished the cast products; and teachers. Women supplemented family incomes by sewing, lodging and boarding single workers, and laundering. Some made extra income working as woodcutters and miners. Farmers fed the community, and some worked the furnace for part of the year. African Americans also worked furnaces – enslaved at first, later as temporarily employed runaway slaves and free blacks. The blacksmith was an important member of the furnace community, responsible for making wagon-wheel tires and farm, mine, and furnace tools, and assisting with furnace and farm repairs. Some specialized workers preformed work as needed. These workers included weavers, the tailor, the cabinetmaker, the mason, and the wheelwright.

As many as thirty-three different jobs have been defined in records kept by the clerk at Hopewell Furnace. Most devoted their time to gathering materials for the furnace, including cutting wood, making charcoal, mining, and driving teams. The number of workers varied each blast, with as many as 246 in the 1835-1837 blasts working six days a week, Monday through Saturday. |

Last updated: February 4, 2025