NPS Illustration. For centuries charcoal was one of three resources that went into making iron. The other two resources were iron ore and a flux, usually limestone. Of the three, charcoal was the only renewable resource, but also the most expensive one to acquire. It could not simply be mined, but was created through a time-consuming, delicate process. An immense amount of charcoal was required to keep a furnace the size of Hopewell's running. When it was "in blast," the furnace would consume as much as 800 bushels of charcoal per day. Using charcoal to make iron was a processes that came to America from England. By the 1770s, when Hopewell Furnace began making iron, charcoal was the only fuel available. The 19th century, however, brought experiments in the process through the use of anthracite or "hard" coal in place of charcoal. In 1837 a Pennsylvania furnace was successful in producing iron using anthracite coal with the use of a hot air blast. Though iron production with anthracite coal was briefly tried at Hopewell during the 1850s, it did not prove to be economically viable due to the added expense of hauling it to the furnace. Hopewell continued to operate as a charcoal furnace for over four decades after most of the iron industry shifted from charcoal to anthracite coal, but in 1883 Hopewell Furnace "blew out" for the final time, losing in business to the newer anthracite fired furnaces.

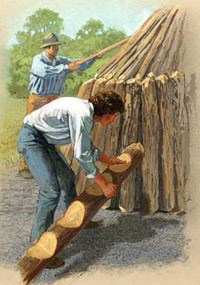

NPS Illustration. Throughout the furnace's history, woodcutters were the largest group of furnace employees. Of the nearly 250 workers on the payroll from 1835 to 1837, more than 100 were woodcutters. Most woodcutting was done in the winter, when idle colliers were joined by part time employees such as neighboring farmers with time on their hands, unemployed boys, and even women hoping to earn a few dollars. Using only axes, saws and splitting tools, woodcutters could produce an average of two cords of wood per day. While this may appear to be a large quantity of wood, when converted to charcoal this was only enough to keep the furnace operating for about 2 1/2 hours. An average charcoal hearth of 30 cord of wood converted into approximately 1100 bushels of charcoal, enough to keep the furnace operating for about 1 1/2 days. The annual requirement for charcoal at Hopewell consumed 6000 to 7000 cords of wood, or 200 acres of woodlands each year. Despite popular myths, charcoal making did not lead to the deforestation of the area. The best kind of wood for making charcoal was hardwood trees that were 25 - 30 years old. A furnace with about 6000 acres of forest could create a system in which woodcutters would cut what they needed from a specific area, then take measures to prevent livestock from eating the new growth, and decades later, woodcutters would work their way back around to this area and cut again.

NPS Illustration. Making charcoal required constant attention to the charcoal pits, or hearths, which averaged in size from 30-40 feet in diameter. From May through October, a collier would live in a makeshift hut with one or two helpers who would tend up to 8 or 9 pits at one time. There could be no break in the vigilant watching of the pits from the moment they were lit until the moment the teamster drove away with the final load of charcoal. The process includes numerous steps:

To understand the charcoal-making process at Hopewell Furnace, a program was conducted in 1936 during which 82-year-old Lafayette Houck, one of Hopewell's last colliers, and his son, William, gave a living demonstration of the life of a collier. Even today Hopewell continues to have charcoal-making demonstrations which produce charcoal using traditional methods with the support of numerous dedicated park volunteers.

|

Last updated: February 4, 2025