Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library, National Archives Today, two granite monuments stand on either side of the Potomac River. These are memorials to Lyndon B. Johnson and Martin Luther King, Jr. Little seems to connect them. One is filled with remarkable calls to justice. The other is a landscape of pine trees. But for two years they strategized together—behind closed doors and during secretly recorded phone calls. They came together in the days after President Kennedy’s assassination. From 1963 to 1965, their coordination helped to push forward the landmark civil rights laws of the 20th century. Johnson and King’s relationship was as critical to those legislative victories as Johnson’s public speeches and dealings with Congress. Yet the relationship was often filled with tension. Neither Johnson nor King promoted their collaborations publicly. Their advisors viewed each other with suspicion. And the FBI, under J. Edgar Hoover, actively tried to destroy King’s public reputation. Nonetheless, Johnson welcomed King’s support, strategized with him, and used the tools of King’s non-violent direct action campaigns to build public backing for legislation. King’s efforts towards racial equality had been in the public eye since the 1955 Birmingham Bus Boycott. In 1963, as president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), King coordinated another high-profile anti-segregation campaign in Birmingham, Alabama. The collective pressure of Birmingham and other civil rights efforts compelled President John F. Kennedy to submit a landmark Civil Rights Act in the summer of 1963. That August, the March on Washington and King's “I Have a Dream” speech increased public pressure to pass the Kennedy civil rights bill. [2] Johnson had supported civil rights legislation when he served as Senate majority leader, including passing moderately successful civil rights laws in 1957 and 1960. Johnson courted King’s support almost immediately after becoming president. On November 25, 1963, three days after Kennedy’s assassination, Johnson called King to thank him for “your cooperation and communication.” During this phone call, King suggested to Johnson that, “I think one of the great tributes that we can pay in memory of President Kennedy is to try to enact some of the great, progressive policies he sought to initiate.” [3] Johnson’s first formal address as president echoed King’s words from their phone call. The new president told the mourning nation, “No memorial oration or eulogy could more eloquently honor President Kennedy’s memory than the earliest possible passage of the civil rights bill for which he fought so long.” Johnson had fully tied the civil rights bill to Kennedy’s memory and his administration to civil rights. [4]

Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library, National Archives The Civil Rights Act faced fierce opposition in the Senate. Southern segregationists used the filibuster to pause the bill and weaken it. However, Johnson and his allies in Congress created a bi-partisan coalition to overcome the filibuster – a first in history for a civil rights bill. [5] Johnson signed the legislation on July 2, 1964. It illegalized segregation in public spaces and outlawed racist employment practices. King can be seen in the historic photographs standing right behind the president. Following the Civil Rights Act, King offered public support to Johnson during the 1964 presidential campaign. King’s reputation was immense, and he had just been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. King’s support of the Democrat nominee helped Johnson win the largest share of the popular vote in over a century. [6] King’s efforts after the 1964 election would keep the national spotlight on civil rights activism and encourage Johnson’s efforts to pursue further voting rights legislation. Johnson was determined to create a strong Voting Rights Act. Johnson revealed his voting rights legislation to King several weeks before publicizing his goals in his 1965 State of the Union address.

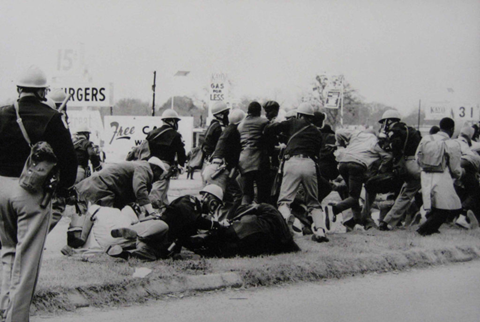

Washington University Libraries, Henry Hampton Collection Civil rights activists were already ahead of Johnson. They would push the president to pursue voting rights much sooner than he imagined. Local activists had contacted King and the SCLC to support a voting rights campaign in Selma, Alabama. Due to voter suppression laws, less than 2% of Selma’s Black residents were registered to vote. During the campaign several activists were murdered. The most visible event came on March 7, when hundreds of voting rights activists began to march from Selma to Montgomery. The marchers were met with violence by state and local police. Television cameras broadcast the brutal events of what came to be known as “Bloody Sunday.” The leadership and courage of voting rights activists in Selma gave Johnson the political momentum to pursue the Voting Rights Act without delay. A week after Bloody Sunday, Johnson introduced the bill with the urgency of Selma in the national mind: “What happened in Selma is part of a far larger movement which reaches into every section and State of America. It is the effort of American Negroes to secure for themselves the full blessings of American life. Their cause must be our cause, too. But it is not just Negroes, but really it is all of us, who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice. And we shall overcome.” [8]

Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library, National Archives Johnson’s statement of “We Shall Overcome” invoked the anthem of civil rights activists. The Voting Rights Act passed in four months. The bill outlawed racially motivated literacy tests and poll tests. The majority of Southern Black voters had access to the ballot box for the first time in American history. Johnson called its passage “a triumph for freedom as huge as any victory that has ever been won on any battlefield.” [9] However, the Johnson and King’s relationship began to strain under the weight of the growing conflict in Vietnam. King spoke out against the war just as Johnson increased the level of troops. By 1967, King forcefully condemned Johnson’s policies, and would later remove his support for Johnson’s candidacy. The former allies, however, did not stop pursuing their social and legislative agendas. King envisioned a new stage in the Civil Rights Movement. He wrote, “with Selma and the Voting Rights Act, one phase of development in the civil rights revolution came to an end.” King last book offered the question of “where do we go from here?” King directed his followers to turn towards issues of economic security like better jobs, higher wages, decent housing, and equal education. [10] On April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated during his efforts to pursue this Poor People’s campaign. Johnson’s political future crumbled with the ongoing war in Vietnam. His domestic agenda slowed as he turned attention towards the overseas conflict. And Johnson dropped out from the 1968 campaign a week before King’s assassination. Despite personal conflict, Johnson stated, “I have rarely felt that sense of powerlessness more acutely than the day Martin Luther King, Jr., was killed.” Just as he had with Kennedy’s death, Johnson harnessed the energy around King’s assassination to pass a third major civil rights legislation. Using King’s association with fair housing activism, Johnson helped pass the 1968 Civil Rights Act, also called the Fair Housing Act. [11] Johnson also expressed King’s question about the future – where do we go from here In one of his last public appearances, Johnson said, “While the races may stand side-by-side, Whites stand on history’s mountain and Blacks in history’s hollow. And until we overcome unequal history, we cannot overcome unequal opportunity.” [12] For now we might ponder that the question where do we go from here, has yet to be fully answered. [1] LBJ phone conversation with Martin Luther King, Jr. January 15, 1965. https://millercenter.org/the-presidency/secret-white-house-tapes/conversation-martin-luther-king-january-15-1965 [2] Martin Luther King, “In a Word-Now,” New York Times Magazine, September 29, 1963. [3] A Conversation between LBJ and Martin Luther King, Jr. November 25, 1963. http://www.lbjlibrary.org/lyndon-baines-johnson/timeline/a-conversation-between-lbj-and-martin-luther-king-jr. Kent Germany, “Lyndon Johnson and Civil Rights,” Miller Center. [4] President Johnson’s address to a joint session of Congress, November, 27, 1963. [5] “Civil Rights Act of 1964,” senate.gov. [6] “Lyndon Baines Johnson,” Martin Luther King Institute. [7] LBJ phone call to MLK, January 15, 1965. [8] President Johnson’s Special Message to the Congress: The American Promise. March 15, 1965. https://www.archives.gov/legislative/features/voting-rights-1965/johnson.html [9] Lyndon Johnson, “Remarks at the Capitol Rotunda,” August 6, 1965. [10] Martin Luther King, Where Do We Go From Here? Chaos or Community, (Beacon Press: Boston, 1967.) [11] “History of Fair Housing,” HUD.gov [12] Lyndon Johnson. Civil Rights Symposium Address. December 12, 1972. |

Last updated: February 15, 2021