|

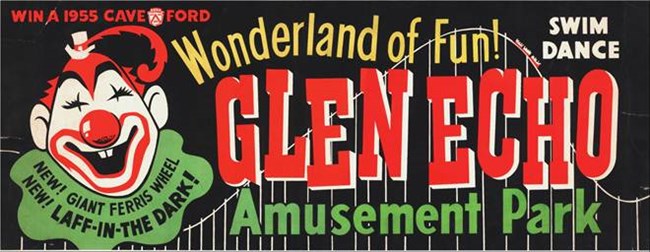

From its beginnings, Glen Echo Amusement Park enforced a strict segregation policy, allowing only whites to enter and enjoy the park grounds. In the summer of 1960, this unfair treatment was challenged by a group of brave individuals united by the common goal of equality and justice for all people, regardless of their color or creed. Their actions that summer would forever change Glen Echo Park and would mark a milestone in their own personal lives.

A PDF of the "Summer of Change: The Civil Rights Story of Glen Echo Park" is also available to download.

National Park Service, Glen Echo Park Photo Archives The District of Columbia began to integrate starting with the school system in 1953. Suburban communities in Maryland and Virginia did not follow suit. By 1958, Montgomery County Public Schools were forced to bus African American students to integrated DC pools, while white students continued to take advantage of places like Glen Echo Amusement Park's Crystal Pool.

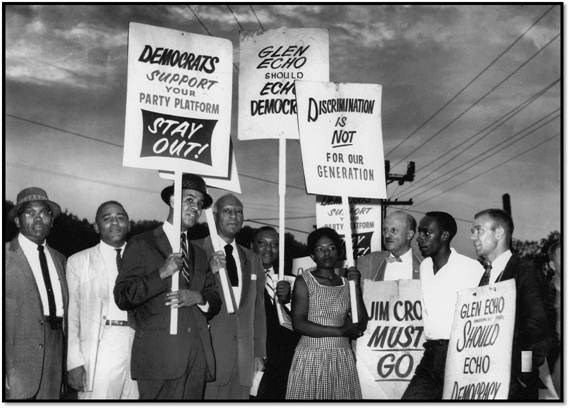

A group of concerned residents, concentrated in the local community of Bannockburn, began to lobby for county-wide accommodation laws and protested the use of public funds for programs at the segregated, privately owned Glen Echo Amusement Park.

In the spring of 1960, a group of students - many from Howard University - organized themselves as the "Non-violent Action Group" (NAG) and began protesting Northern Virginia lunch counters, restaurants, and department stores. During the summer of 1960, they came to Glen Echo Amusement Park. The Bannockburn residents would prove a willing ally during that summer of change.

National Park Service, Glen Echo Park Photo Archives F. Collins [FC]: Are you white or colored?

L. Henry [LH]: Am I white or colored?

FC: That's correct. That's what I want to know. Can I ask your race?

LH: My race? I belong to the human race.

FC: All right. This park is segregated.

LH: I don't understand what you mean.

FC: It's strictly for white people.

LH: It's strictly for white persons?

FC: Uh-hum. It has been for years...

LH: You're telling me that because my skin is black I cannot come into your park?

FC: Not because your skin is black. I asked you what your race was.

LH: I would like to know why I cannot come into your park.

FC: Because the park is segregated. It is private property.

LH: Just what class of people do you allow to come in here?

FC: White people.

LH: So you're saying you exclude the American Negro?

FC: That's right.

LH: Who is a citizen of the United States?

FC: That's right.

LH: I see.

National Park Service, Glen Echo Park Photo Archives But they were neither alone nor unopposed. Shortly after picketing began, a counter-demonstration was instigated by George Lincoln Rockwell and the American Nazi Party. While no picketers were harmed, there was a constant threat of violence - a rock thrown, a bottle tossed - for those struggling to provoke change.

At the park's close on September 11, 1960, the protesters dispersed and vowed to return. Civil disobedience then sparked political manuevering. Bannockburn resident and newly appointed assistant to the Secretary of Commerce, Hyman Bookbinder, sought assistance from US Attorney General Robert Kennedy in February 1961. Kennedy threatened to have the federal government revoke the lease upon which the trolley ran.

Such manuevering, in addition to the summer protest, led to the March 14, 1961, announcement that the park would open its doors to any patron, regardless of skin color.

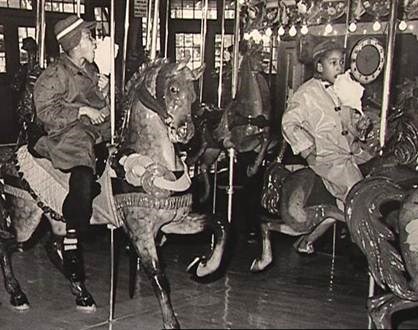

National Park Service, Glen Echo Park Photo Archives The original carousel still operates and the trolley tracks are also still around, though the trolley car no longer operates on it. Visitors can sit on the same animals the protesters sat on and walk in their footsteps along the tracks as they did over 50 years ago.

|

Last updated: August 3, 2021