Mapping Parklands

In their most basic

form, maps show us where things are and how to get there. We pore over

wrinkled road maps on summer vacation. We print out Internet directions

to the nearest post office or supermarket. At the mall, we check the

wall

map to save our tired feet from a wrong turn. In our national parks,

maps

point us to the geyser basin, natural bridge or waterfall we came to

experience.

Maps and geographic information have always served another, larger

purpose

in the National Park Service, to preserve America’s most special places

for our benefit, enjoyment, and education.

In the

early days, cartographers created hand drawings of parks to illustrate

such features as wagon trails, cattle grazing areas, wildfire

perimeters,

battlefield topography, and stream meanderings. Some of the earliest

maps

came from John Wesley Powell and his expedition through the Grand

Canyon

and from the U.S. Army Fifth Cavalry at Yosemite in 1896. Field maps

from

military cartographers and surveyors have helped national parks

recreate

authentic landscapes for visitors to see where their ancestors fought

and

died during the Revolutionary War, War of 1812, and Civil War.

Today, the park

service combines the best of early cartography with the latest

technology

to collect and display geographic information. Relatively new mapping

tools

include GIS software, global positioning systems, satellite photography

and storage of national park maps on computers for easy access and

review.

The park service now spends more than $17 million annually on

geographic

data. It is a grand endeavor of more than 11,000 topographic map sheets

representing more than 84 million acres. The park service and other

partners

together are mapping soils, plant life, geology, and other earth

science

themes at more than 388 national parks. The ongoing program eventually

will produce the first standard set of digital national park base maps.

Using GPS and hand-held

computers in the field, the park service can more accurately pinpoint

locations

of archeological sites, endangered species, and nesting areas and then

download them into GIS maps for review. A GIS map can show the

geographic

relationship of bird nest areas to soils, erosion rates, elevation and

vegetation in that area. The ability to display all the information

layers

on a single map helps park managers as they decide where to release

captive-bred

California condors into the wild, close a trail to protect newborn

bighorn

sheep, or increase patrols against artifact theft.

Most mapping

and geographic studies now extend beyond national park boundaries. They

might display the relationship of the park to streams, coastlines,

glaciers,

rock formations, hazardous waste cleanup sites, and even cities. The

park

service works with several federal agencies and other groups to collect

geographic information using sophisticated sensors on satellites,

aircraft,

balloons, ships, and submarines. Displaying the information on GIS maps

helps the park service compare different types of data. GIS technology

can help park managers predict how various factors, such as drought,

shoreline

changes, or increased thermal activity, might affect a park. The power

of GIS helps us relate, analyze, and model historic and current

features

and phenomena within a particular study area. Without new technology

and

geographic information, the National Park Service would face a

difficult

and sometimes impossible task to measure, map and understand America’s

changing landscape and environment.

Leslie Armstrong,

Chief,

Geographic Information Systems Division

National Park Service

Articles:

Tim Connors, Capitol Reef NP

Geology.....it's not just for scenery

anymore

GIS and cartographic tools are

particularly

important to the geologists working in national parks. Geology, often

scoffed

at as merely being attributable only to scenery, actually play a much

wider

role in the ecosystem. The importance of geology to our everyday

activities

is obvious to the geologist: it ranges from shaping the earth’s surface

to controlling where we eventually settle in communities. With GIS, the

geologist can illustrate the importance of the science of geology to

others,

including soil scientists, botanists, and ecologists, and national park

visitors. Capitol Reef National Park in Utah uses GIS maps help predict

habitat for threatened and endangered species, including Winkler’s

cactus,

Barneby reed-mustard, and Jones cycladenia. The park also found a

direct

link between the presence of several plant species and Navajo

sandstone.

Geologic maps describe underlying conditions of natural systems and are

key in the study of ecosystems, earth history, soils, and environmental

hazards such as fires, landslides, and falling rocks. When combined

with

GIS technology, these maps have advantages over traditional paper

geologic

maps. GIS maps display the relationship between the earth’s surface and

bedrock to data on soil, vegetation, water and other features. It

allows

study of all these features on a single precise map for fast, easy

review

and creates a powerful database. The park service has developed many of

its digital maps using ArcView software developed by ESRI.

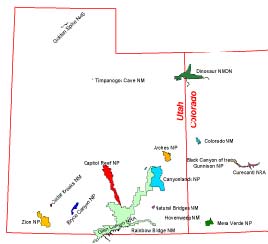

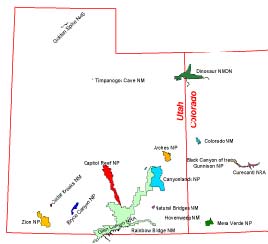

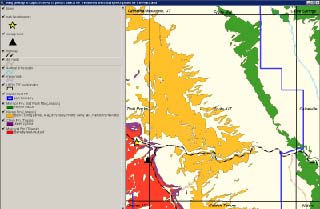

Figure 1. National Park Service

areas

in Utah and western Colorado; Capitol Reef NP shown in red

|

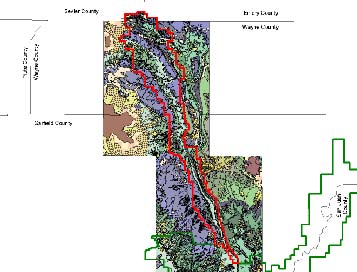

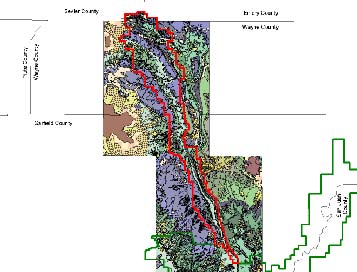

Figure 2. Digital geologic map of

Capitol

Reef NP and surrounding area (produced by NPS Geologic Resources

Inventory

staff from Billingsley, G.H., Huntoon, P.W., Beard, W.J., 1987,

Geologic

Map of Capitol Reef National Park and Vicinity, Utah, Utah Geolog

|

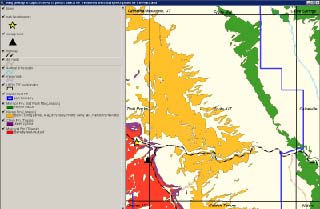

Figure 3. Derivative map showing

occurrence

and distribution of a few threatened and endangered species and their

ties

to geologic units in the Fruita area of Capitol Reef NP.

|

Geology.....it's not just

for scenery

anymore

PDF

Version

Word

Document

|

Click for Technical Article

Bill Eichenlaub, Glacier Bay NP

Data Access

Glacier Bay National Park

and Preserve connects us to wild Alaska, now and for all time. Its tidewater

glaciers, deep

fjords, mossy rainforests, rugged coastline, and snow-capped peaks

provide a

living laboratory to explore the natural world. Its diverse landscapes

and

seascapes support wildlife ranging from humpback whales, porpoises, and

harbor

seals, to black bears, wolves, and tufted puffins. A mosaic of plant

life

blankets the coastal and alpine regions, including alder, spruce,

heath, spongy

muskeg, and a few species in areas released from the grip of glaciers.

These

complex ecosystems present park managers with scientific information

ranging

from detailed undersea profiles to the distribution of bear habitat.

The

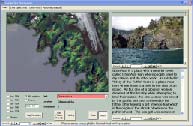

national park at Glacier

Bay uses GIS

technology to display complex and voluminous

information in map-enabled databases for fast and easy access to data,

aerial

and ground photographs, sound files, and video. These databases provide

instant

spatial access to tens of thousands of photos, many taken in remote

areas that

the average park manager may never visit. A manager can zoom in on the

map,

click on a point, review all the photos taken there, see graphs of

scientific

data, view a species list specific to that site, even read the notes

taken by

the field crew at the site. One database stores information about the

distribution of whales in Glacier Bay, helping managers decide where and when to

restrict sea-going vessels in the summer tourist season. Another

database on

bear sightings and bear-human interactions helps managers decide when

to close

remote campsites to protect visitors and their belongings. Another

project

includes a talking map that helps Native American students learn the

traditional names of local places and provides them a crucial link to

the

cultural landscapes of Glacier

Bay. These are just

some of the ways the national

park uses databases supported by GIS technology.

Click for Technical Article

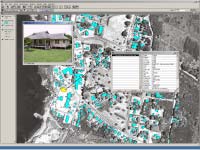

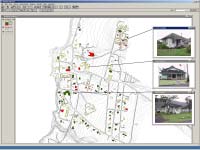

Thomas Fake, Kalaupapa NHP

FMSS and LCS Integration at Kalaupapa

NHP

Kalaupapa National Historic Park

contains

the setting for two tragedies in Hawaiian history. The first was the

forced

removal of indigenous people in 1865 and 1895 from an area where they

had

lived for more than 900 years on the island of Molokai. The second was

the forced isolation of thousands of Hawaiians sick with leprosy

between

1866 and 1969, first at Kalawao and then at Kalaupapa. Many surviving

patients

of Hansen’s Disease, or leprosy, still live at Kalaupapa. Hundreds of

historic

buildings remain, and distinct neighborhoods support many activities of

daily life. The National Park Service and state of Hawaii have been

putting

these historic buildings under the park’s care since its creation in

1980.

The park reviewed the historic value of each structure and identified

more

than 200 buildings as a high priority for preservation. ArcView

software

developed by ESRI displayed the location of each historic building on

an

interactive GIS map. The map contains data on the condition of each

building,

and the work and money needed for restoration. The ability to join GIS

data to other databases has given managers a new tool to preserve

history

at Kalaupapa.

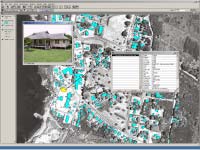

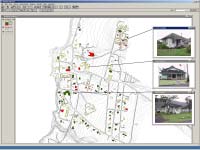

Kalaupapa NHP Facility Management

Software

System (FMSS) Buildings Asset Layer

|

Kalaupapa NHP LCS Condition

Assessment

with Photographs

|

Kalaupapa Settlement Screen Capture

with

ID of Bay View Building 1

|

List of Classified Structures

Condition

Ratings For Buildings with 3 Photo Examples

|

Click for Technical Article

Jess Grunblatt,

Alaska

Support Office

Flexible Image Classification With

ARCGIS

The 15 national parks of Alaska cover

54

million acres of some of the most pristine lands in America. From

glaciers

to grasslands and from polar bears to reindeer, these parks feature an

incredible variety of, habitat, wildlife, and plant species across vast

ecosystems. Mapping the health and analyzing trends in these theses

ecosystems

has become a job for GIS. At Katmai National Park and Preserve, GIS

specialists

used ArcGIS software developed by ESRI, satellite images and other

technology

to map the types of vegetation in a study area of more than 4 million

acres

of rugged, remote wilderness. As a result of this work, Katmai produced

a final, generalized map showing the land cover of the entire park.

These

GIS-based maps help park managers evaluate the condition of ecosystems

and make planning decisions to guide their preservation.

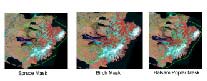

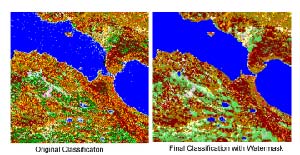

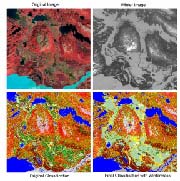

Illustration of species distribution

masks

for Katmai vegetation mapping.

|

Illustration of water model results

as

implemented for Katmai vegetation mapping.

|

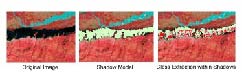

Illustration of winter image model

results

as implemented for Katmai vegetation mapping.

|

Illustration of shadow model results

as

implemented for Katmai vegetation mapping.

|

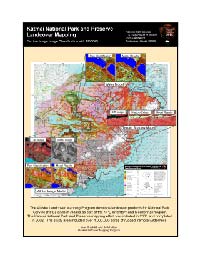

Poster summary of the Katmai

Vegetation

Map including final vegetation map and models.

|

|

Click for Technical Article

John Pinamont, Alaska

Support Office

Map Products

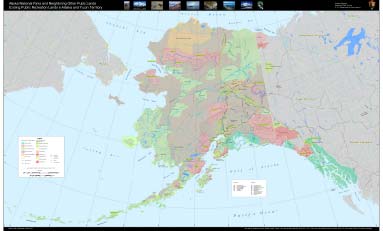

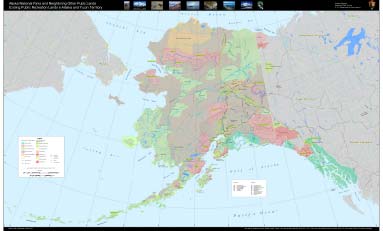

The unique GIS map, “Existing Public

Recreational

Lands in Alaska and Yukon Territory” shows all the public lands of

Alaska

on one sheet. The map provides vital information for regional planning

in the state’s national parks, based on data collected from state and

federal

agencies and the Internet. It is one of a series of digital maps

distributed

to national parks in Alaska that helps scientists and managers use GIS

technology in their daily work. Another popular GIS map shows the

national

parks of Alaska in relation to federally designated “Wild and Scenic

Rivers.”

The park service also produces GIS maps on paper, including several

statewide

maps and a series of park maps for many uses, including wilderness and

fire management.

Public Recreation Lands in Alaska

and

Yukon

|

Click for Technical Article

Dave Schirokauer, Point Reyes NS

Enhanced Wetlands Mapping at Point

Reyes National Seashore

Point Reyes National Seashore in

northern

California offers haven to thousands of migratory birds and more than

50

animal species, including elephant seals, gray whales, and tule elk.

Its

ocean views, winding trails, and historic lighthouse offer inspiration

and recreation. Its rare coastal wetlands feature salt, brackish, and

freshwater

marshes, meadows, and seasonal ponds. This national park aims to

preserve,

protect and restore these invaluable wetlands from hazardous material

spills,

failing septic systems, beef and dairy operations, construction, and

from

historic neglect and abuse of the land. As a preservation tool, GIS

technology

helps the National Park Service accurately map the location, size, and

type of wetlands as a way to evaluate environmental damage and plan

restoration.

In one case, field crews identified plant species found in wetlands of

the 4,000-acre Abbotts lagoon. The park displayed the botanical

inventory

on a detailed GIS map for research, planning and public review.

Wetlands in the Abbotts Lagoon

Watershed

displayed with Cowardin System, Class, and Water Regime Modifier

|

A detail of a portion of the

wetlands

in the Abbotts Lagoon Watershed displayed at the finest level of

thematic

resolution with Cowardin System, and NWI code.

|

Click for Technical Article