Art and a New Understanding of Place

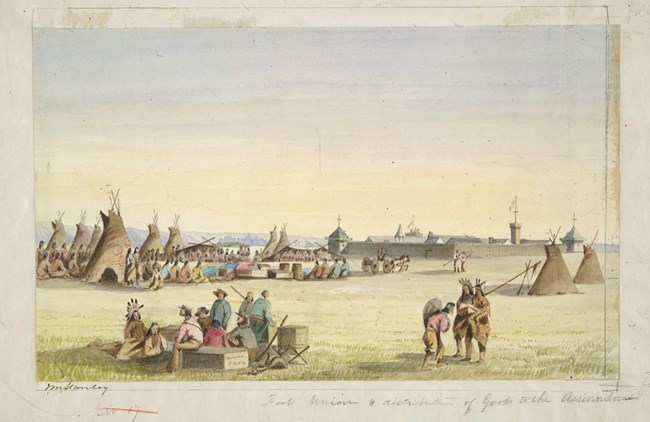

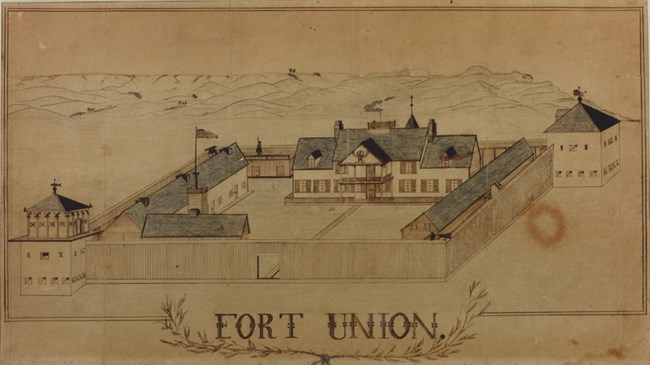

Without the archeologists’ discoveries, today’s reconstructed Fort Union would not exist. Their findings, especially unearthed foundations, revealed dwelling locations, building methods, and construction sequences. Richard Cronenberger, the NPS’s historical architect, worked closely with the archeologists, integrating these findings directly—and sometimes at the last minute—into his architectural plans and drawings. The archeologists could not, however, show what the post’s buildings looked like during the historic period. For appearance, Cronenberger relied on existing written descriptions and the sketches and paintings George Catlin, Karl Bodmer, Rudolph Friedrich Kurz, John Mix Stanley, and other artists created between 1832 and 1867. Even detailed architectural renderings produced by soldiers garrisoned at Fort Union in 1864 and 1865 offered valuable insights.

Yale University Art Gallery The artists’ work featured here—a sampling only of the plethora produced—at first documented the landscapes, peoples, plants, and wildlife along the Missouri River and in the vicinity of Fort Union. Exhibited in galleries in American and European cities or reproduced and published in newspapers and magazines, these and similar drawings and paintings challenged and inaugurated transformation of the decades-old myth of the western plains as a Great American Desert. Instead of being an inhospitable environment and barrier to progress, today’s Middle West began to be viewed as a place of opportunity.

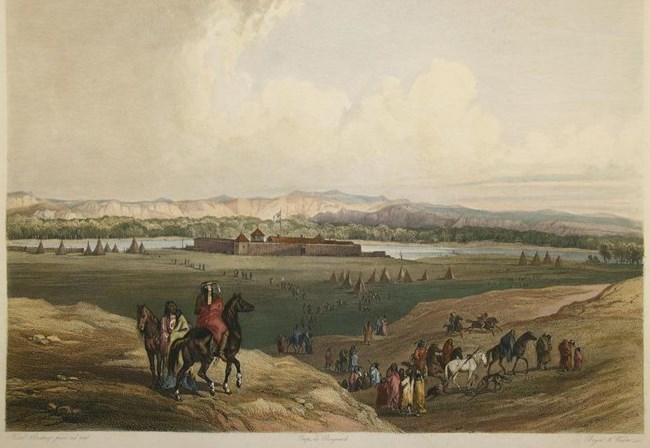

NPS photo Karl Bodmer and His “Very Faithful Drawing”George Catlin may have been the first painter to visit Fort Union. He did not, however, paint the nineteenth century’s most famous image of the American Fur Company’s grandest post. That honor belongs to the Swiss artist Karl Bodmer, whose work includes the century’s most extensive and accurate visual record of the Plains Indian peoples.

A lithographic print of "Fort Union on the Missouri" published circa 1843. NPS photo Maximilian kept detailed journals, which he later synthesized for publication, along with some of Bodmer’s drawings. In those journals, the prince often noted the artist’s new artwork and activities. At least twice during their two-week stay at Fort Union in the summer of 1833, Bodmer explored the hills north of the trade post. “From these hills,” Maximilian wrote in his June 25th journal entry, “one has a beautiful view of the river, the fort, the nearby hill chains, and the vast prairie, on which the forts horses are grazing—about sixty head.” From there, the prince would write later, “Mr. Bodmer made a very faithful drawing” of the Missouri and Yellowstone River’s confluence. That day’s and his July 2nd sketches inspired and informed the artist’s later completed and frequently reproduced “Fort Union on the Missouri,” which is featured in this exhibit. |

Last updated: April 24, 2021