Women's Contributions Greater Than Realized

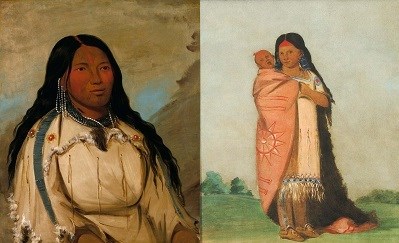

Smithsonian American Art Museum. Gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison, Jr. 1985.66.178 (left) and Smithsonian American Art Museum. Gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison, Jr. 1985.66.177 (right). Even today, the fur trade and its history are portrayed as the realm of men—of bearded, leather-clad mountain men and rugged individualists. Women at best are cast as secondary figures in supporting roles. But that is wrong. And we know it. Fort Union’s past is a case in point. If not for women like Natawista, who married Fort Union Bourgeois Alexander Culbertson, their fur-trader husbands and partners would never have been as successful as they were, nor Fort Union as grand as it was. And the same is true today. Look again at the exhibit’s panels and photographs. How many women do you read about or see? Among the historians and archeologists, there are women. There are women among the volunteers and in leadership roles directly engaged in Fort Union’s preservation and reconstruction. Even the most recent published histories directly relevant to Fort Union are those researched and written by women: Lesley Wischmann’s Frontier Diplomats: Alexander Culberston and Natoyist-Siksina among the Blackfeet; Doreen Chaky’s Terrible Justice: Sioux Chiefs and U.S. Soldiers on the Upper Missouri, 1854–1868; and Anne F. Hyde’s Empires, Nations, and Families: A New History of the North American West, 1800–1860.

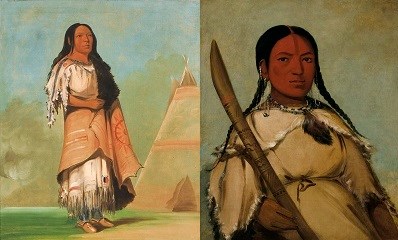

Smithsonian American Art Museum. Gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison, Jr. 1985.66.155 (left) and Smithsonian American Art Museum. Gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison, Jr. 1985.66.180 (right). Can that be changed? What stories can you share? We invite you to leave your thoughts and suggestions. Or share them with the park staff. The curator’s contact information is included in the exhibit’s last panel. Consider joining the many women involved in Fort Union’s thriving volunteer program. Helps us all fulfill our National Park Service Centennial goal to “connect with and create the next generation of park visitors, supporters, and advocates.” Mary Culpin, the Historian Who Aided ReconstructionBy the 1980s, poor and inaccurate historic reconstructions done decades earlier left many in the National Park Service (NPS) opposed on principle to reconstruction. Regarding Fort Union, professional historic preservationists and NPS officials believed too little original information still survived to make an accurate reconstruction possible. Enter Mary Shivers Culpin. North Dakota Representative Mark Andrew’s insistence had prompted Congress in 1978 to authorize Fort Union’s reconstruction; it gave the NPS a year to report back on the reconstruction’s viability. Culpin, an NPS historian, was, in her words, directed “to find material [in archives around the country and world] that would document the appearance of the fort and any new descriptive information. The search for artistic renderings, early stereopticon views, sketches, diaries, journals, field notes, and other sources led our [NPS] team” in 1979 to recommend “a partial reconstruction.”

NPS photo Years later, when speaking about the Swiss artist and 1851–1852 Fort Union clerk who drew many sketches that she and Cronenberger used to guide the reconstruction, Culpin said, “I know that somewhere out there a [Rudolph] Kurz drawing of the Indian Artisan House and river gates painted from the front porch of the Bourgeoise [sic] House will be found.” “Once a person becomes involved in a major project” like this, she reflected in 1991, “the possibilities of discovering something new remains with you.” |

Last updated: April 24, 2021