Arrows, Guns, and Buffaloby Dana Dick, Student Conservation Association Intern

NPS. Top to bottom, from left: Knife River flint oxbow point (FOUS 49993), Swan River chert besant point (FOUS 3909), Porcellanite plains side-notched point (FOUS 99186), iron point (FOUS 16782), copper point (FOUS 98266), brass point (FOUS 16795). The bow and arrow was an indispensable tool for American Indians living on the Great Plains by CE 250 at the latest. When Europeans emigrants founded Jamestown in 1607, the Plains Indian peoples had long ago perfected their bows and arrows into powerful weapons for hunting game and waging war. The bow and arrow worked so well, in fact, that American Indians relied on this traditional weapon long after they adopted firearms from the Europeans. Despite popular belief, they preferred them to the gun even into the late 1800s. How could that be? The Gun’s PopularityOn the Northern Plains, American Indians obtained the gun through exchange at posts such as Fort Union. Imported from England, Belgium, France, and the American Colonies (later, the states), the gun became a popular trade item for tribal members. Possibly the most iconic fur trade firearm was the Northwest Trade Gun. This weapon was manufactured specifically for the fur trade and marketed to American Indians. For nearly two centuries after its introduction, this gun was sold by almost every company involved in the fur trade. Fort Union’s inventories, correspondence, and orders indicate that the post kept large quantities in stock and placed large orders for more every year. Edwin T. Denig, the Fort Union Bourgeois, or manager (1848–1854), specifically mentioned the Assiniboine people’s use of the Northwest Gun in his 1850s report on the Plains Indians for the Federal government. “The bow and arrow is used altogether by all these tribes when hunting buffalo on horseback,” Denig wrote, “and the Northwest shotgun is the only arm employed in killing any and all game on foot.” Once guns became available—they could not make their own—they wanted ones that were cheap, light, serviceable, and reliable in any season. The Northwest Trade Gun supplied just that. But even with the popularity of firearms, American Indians still depended on their bows and arrows.

NPS. In addition to the oxbow, besant, and plains side-notched points on the right side are a Knife River flint corner-notched Pelican Lake (middle, FOUS 3911), Porcelanti side-notched (left, FOUS 71265), and plains side-notched (middle, FOUS 99187) point Their Weapons and TradeUp to the time of the fur trade, hunters and warriors had made bows and arrows from locally sourced or traded natural materials. For arrowheads, or projectile points, they relied on a variety of resources, primarily stone, bone, and antler. Chert, flint, and obsidian were the types of rock most often obtained to manufacture these early lithic points. Because they could not be found everywhere in North America, these rocks were traded across vast distances over well-established trade routes. Knife River flint is one point-making stone that traveled great distances. For the most part quarried in central-western North Dakota, Knife River points have been found in archeological sites across North America – from southern Canada to the Texas Panhandle and from the Rocky Mountains to Ohio. Another lithic material traded over great distances was obsidian from the Obsidian Cliff in Yellowstone National Park. Archeological evidence indicates that American Indians quarried that site for more than 10,000 years. Archeologists have found that obsidian as far north as Canada, south into Colorado, west into Washington, and east into the Ohio River Valley. The intense mining activities at these two sites, as well as the great distance the stones traveled, indicate the importance of both projectile points and the existing trade networks used by North America’s earliest peoples.

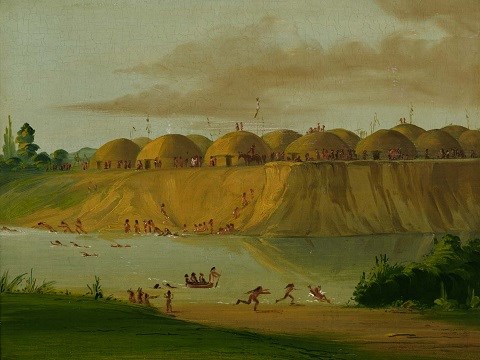

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison, Jr. 1985.66.383. Complex systems of intertribal exchange flourished as a result. People used these trade systems for thousands of years, if not longer, and the concept was nothing new. The Mandan and Hidatsa’s semi-permanent villages along the Missouri River in central North Dakota had thrived as trading centers long before Europeans arrived. At these farming villages, nomadic Northern Plains tribes could trade items of the hunt for ones produced by the village agriculturists. In the early 1800s, the American Fur Company and individual posts like Fort Union tapped into these existing trade systems. Along these ancient routes, new fur trade–supplied goods spread rapidly across the continent. Guns came west with the French and English from the Great Lakes and farther east, while horses came north from Spanish territories in today’s Southwest. The Assiniboine traded guns to the Mandan as early as 1738, by which time nomadic tribes from the south possessed horses. In this way, distant tribes acquired European goods before the American Fur Company established its Upper Missouri River trading posts.

NPS What Does Change?Trade items Europeans brought, including guns, had long-lasting impacts on North America’s existing tribal cultures. In what some scholars call a cultural exchange, items made by American Indians began to be replaced by European goods. The arrival of metal kettles, for instance, lessened the need for pottery making. American Indian women’s acquisition of colorful beads, meanwhile, led to a decline in porcupine quill work and a rise of bead embroidery. Even the bow and arrow changed with metal’s introduction.

NPS. Top to bottom: bone projectile point, ferrous projectile point (FOUS 84275), metal projectile point (FOUS 58276), and iron projectile point (FOUS 16788). By the middle 1800s, posts such as Fort Union were a major source for metal arrowheads. However, unlike the Hudson Bay Company that placed orders for factory-made metal points, Fort Union’s clerks appear not to have ordered pre-made metal points. Although known fort invoices omit mention of metal arrowheads, Fort Union’s archeological excavations unearthed several metal points. How could that be? The discovery of the one bone projectile point at Fort Union (FOUS 787) may provide an answer. This bone point looks almost identical to a number of metal ones that archeologists found. These similarities suggest that the bone point may have been a template for making metal ones. A Fort Union blacksmith could have accomplished this task by placing the bone template on top of a piece of barrel hoop and then cut around it with a chisel.

Image provided courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison, Jr. 1985.66.408. Why They Favored the Bow and ArrowWhy did the guns fur traders introduced not eliminate the use of bows and arrows until after repeating rifles like the Winchester carbine that appeared in the 1870s? Up until then, both young men and poor warriors used the bow almost exclusively while those who could afford guns still used the bow. A powerful weapon, the bow and metal-pointed arrow could kill a man or buffalo as easily as an early gun. On the northern plains, however, the bow was the weapon of choice for hunting buffalo. Early guns were difficult to load while on horseback and could not be fired with the same speed and agility as the bow and arrow. George Catlin, an American painter who visited Fort Union to observe and record the ways of American Indians, participated in several buffalo hunts and was able to see the power of the bow first hand. “Such is the training of men and horses in this country,” Catlin tells us, “that this work of death and slaughter is simple and easy . . . [W]hen the arrow is thrown with great ease and certainty to the heart; and instances sometimes occur, where the arrow passes entirely through the animal’s body. An Indian, therefore, mounted on a fleet and well-trained horse, with his bow in his hand, and his quiver slung on his back, containing an hundred arrows, of which he can throw fifteen or twenty in a minute, is a formidable and dangerous enemy.” The hunter’s ease and ability to discharge arrows rapidly was a clear advantage over the early single-shot long arm, or musket. This was one reason why American Indians kept the bow and arrow in their arsenal until the arrival of more advanced firearms like the repeating rifle.

NPS. Left to right: iron projectile point (FOUS 1403), iron projectile point (FOUS 84275), iron projectile point (FOUS 85666), and a metal projectile point (FOUS 58276). The tribes’ eventual adoption of the metal-tipped arrow and gun is just one aspect of a larger cultural exchange that occurred in North America following Europeans’ arrival. Such cultural exchanges can be described often as cultural reciprocity, with ideas and goods moving back and forth between two or more cultural groups. This idea of a cultural exchange is one commonly used to explain the relationship between Euro-Americans and American Indians. Tribes’ adoption of metal-tipped arrows and firearms is but one example of how Euro-American culture influenced and at times changed American Indian cultures. For a true reciprocity to exist, however, American Indians also had to affect Euro-American cultures. What influences did American Indian societies and cultures have on Euro-Americans? What knowledge and technologies have Euro-Americans gained from the nation’s first peoples? |