Left image

Right image

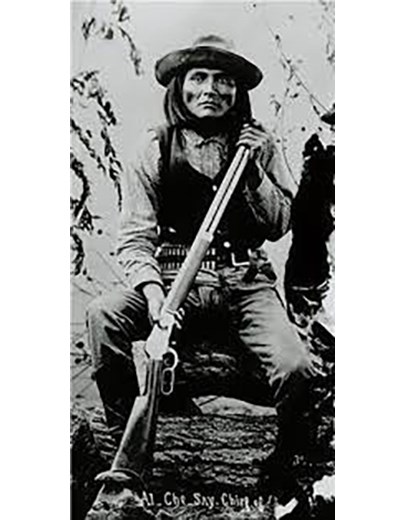

In the years after the Mexican-American War, the frontier Army faced an enormous challenge. An army of 25,000 troops was challenging a population of some 400,000 Indians spread over a vast, largely unknown and roadless area using tactics that were unsuited to the circumstances. To confront this task, the Army relied in no small measure on the contributions of highly skilled, physically tough, brave allies--the Indian scouts. Despite prejudice from many Army officers and hostility from much of American society, the scouts gave vital assistance in some of the Army's most important campaigns. Origins"Finding [the Indians], not fighting them, is the difficult problem to solve," wrote veteran frontier Army officer Wesley Merritt. The Indians knew the terrain, they knew the location of water in dry country, and even as young boys, they were trained to follow signs and tracks in the wilderness. So who better to find Indians than other Indians? In many cases, the Army played off one tribe against another. Natives identified themselves by their tribe, and in many cases, inter-tribal animosities were long standing. In some cases, after the Army suppressed a tribe, it turned around and offered the same tribal members an opportunity to serve as scouts against another tribe. Almost as soon as Fort Union opened in 1851, hostilties began with the Jicarilla Apaches. The new fort was intruding on the traditional lands of the Jicarillas. As Army dragoons pursued a band of Jicarillas through the rugged, mountainous terrain north of the fort, the Army used a company of 32 scouts, including Indians from the Taos Pueblo to chase down the Jicarillas.

Charles Lummis, Library of Congress The Civil War YearsWhen the Civil War started, the Army, worried that Confederates would sneak into New Mexico, made frequent use of natives from the pueblos as scouts to warn of Confederate infiltration. The Army favored Indians (or native Hispanos) because they blended in easily with the local surroundings. When the Army began its harsh campaign against the Navajos in late 1863, Kit Carson, as field commander, used Zunis and Utes as scouts. Carson wanted to permit the scouts to keep their plunder during the Navajo campaign, including livestock and human captives seized as slaves. (This was common practice at the time in New Mexico during fighting between tribes and between Indians and Hispanos.) But Gen. James Carleton, commander for New Mexico, refused to allow it. He did, however, recognize the Utes' talents. "Utes are very brave, and fine shots, fine trailers, and uncommonly energetic in the field," Carleton observed. Recognizing that the United States was distracted by the Civil War, the Comanches and Kiowas stepped up their attacks on the Santa Fe Trail. In response, Gen. Carleton ordered Carson to launch an attack on those tribes. Carson's advance into the Texas panhandle in 1864 included about 350 soldiers and some 75 scouts from the Ute and Jicarilla Apache tribes. Badly outnumbered at the battle of Adobe Walls, Carson retreated--avoiding complete destruction due to the good work of his scouts and the deployment of two mountain howitzers. (The Indians had absolutely no response against American artillery.)

Timothy O'Sulllivan, Library of Congress. The Scouts Become OfficialOnce the Civil War ended, Congress re-organized the Army, greatly reducing its size, but also authorizing the use of African-Americans as soldiers and the use of Indian scouts. Originally pegged to number no more than 1,000, the authorized scouts were limited to no more than 300 after 1874. The scouts' impact was out of proportion to their small numbers. Despite their many successes in the field, the scouts were still controvesial. Some mistrusted their loyalty, some questioned their abilities, and some feared a negative impact on the morale of regular troops. The Symbol of the Scouts

Left image

Right image

The Apache Wars

National Archives Fort Union funneled supplies and troops to the south for the Apache Wars throughout the late 1870s and into the 1880s. The Apaches proved to be the Army's most formidable enemy in the Southwest. The army used Navajo and Apache scouts in these battles. In some cases, the Apache scouts came from the same bands as the hostile Apaches. The scouts were instrumental in the defeat of the renegade Apaches. The mountainous, isolated terrain was treacherous, water was rare, the physical conditioning of the scouts was superb, and they were masters at living off the land. In many of these campaigns, the scouts fought side by side with the Buffalo Soldiers. In the 1879 battle at Las Animas Canyon in southern New Mexico, two Navajo scouts were killed and Navajo scout Hosteen Tsosie was cited for bravery. According to enlistment records, two Navajo women signed up as scouts at Fort Wingate near Gallup, NM, in 1886. Their duties at the time are unclear. In the army's final campaign against Geronimo in 1886, General Nelson Miles used 5,000 army soldiers, 500 Apache scouts and 150 Navajo scouts. A Day of ShameThe long and bitter fight with the Apaches ended in 1886 when Apache leader Geronimo finally surrendered for good--after several aborted surrenders. What should have been a high-five moment for the Apache scouts turned into a debacle. With Geronimo and his followers to be shipped off to prision in Florida, the U.S. Government rounded up more than 200 scouts and family members (who were then living on an Apache reservation) and sent them away with Geronimo.General George Crook, long experienced in Apache warfare and an ardent advocate of the scouts, wrote outraged letters and telegrams in protest of the scouts' treatment. To no avail. The Apaches were held prisoner in Florida until 1894, when they were moved to a reservation at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Finally in 1913, some of the Apaches were allowed to return to the Southwest.

National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution 06667100

National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution 02091700 Medal of HonorSixteen scouts were awarded the Medal of Honor, the nation's highest award for military valor. Nine of the 16 awardees were Apache scouts. |

Last updated: November 18, 2022