Wikimedia Commons, public domain President Abraham Lincoln died in a first-floor bedroom at the Petersen Boarding House at 7:22 a.m. on April 15, 1865. In the moments after Lincoln took his last breath, his friend, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, said: “Now he belongs to the ages.” Today, we understand these words as perhaps the perfect thing to say in that moment. They show Stanton's immediate understanding that Lincoln’s legacy would echo through future generations. Today, we continue to see Lincoln's enduring presence in our world.

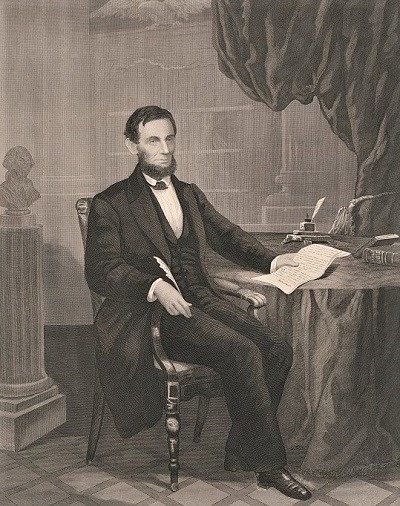

Library of Congress There are countless reasons behind Lincoln's continuing impact. This article will provide a few highlights of one key component of Lincoln’s legacy: his writings. Lincoln's words are an important and relevant aspect of his legacy for modern audiences because they are a part of him that we can still interact with today. His written words give us a tangible measure of the breadth and depth of his many exceptional characteristics. They demonstrate his leadership, empathy, strength, capacity, savvy, and patience. More than 155 years after his death, Lincoln's words help us to define and to understand our America, an America of the 21st century. The timelessness of his words has eternalized a written legacy that has endured long since his own voice fell silent. Abraham Lincoln is often considered one of our most eloquent presidents. He crafted beautifully flowing passages that helped guide a broken nation through a civil war. His writing struck the right balance of literary artistry and simple language. This enabled him to connect his ideas to the masses during an age of print.

Library of Congress Today’s presidents have a variety of ways to communicate with the world. Abraham Lincoln’s main avenue for reaching large audiences was through newspapers. In 1800, there were approximately 250 newspapers in the United States. By 1860, that number had surged to over 2500, more than the rest of the world combined. The desire for information about the Civil War created an even larger newspaper market during Lincoln’s presidency. This medium played a significant role in Lincoln’s writing style. Because newspapers were often shared and read aloud as a form of entertainment, Lincoln “wrote for the ear.” He would whisper or talk out loud as he wrote, to hear how the sentences sounded. He wrote and edited, then he listened. He wanted to hear how the words blended, how the inflections of the sentences helped to enforce a point. Lincoln used alliteration, repetition, metaphors, and contrasts. He was selective about the use of syllables, choosing words based on their melody within a sentence, a paragraph, and the context of the whole work. William Stoddard, assistant to Lincoln’s personal secretaries John Hay and John Nicolay, wrote about this in his diary. He recounted a time when he entered the president’s office to find Lincoln at a long table. The space was cluttered with a variety of newspapers, maps, and “assorted odds and ends” of letters, notes, and orders. Lincoln asked Stoddard if he would be his audience, while he read his work out loud. Stoddard reported that Lincoln said, “I can always tell more about a thing after I’ve heard it read aloud, and know how it sounds.” Clerks in the telegraph office of the War Department reported the same phenomenon. Lincoln sat hunched over a desk in a quiet corner of the large office, reading under his breath as he wrote. He often enjoyed writing in a place away from the distractions of the White House.

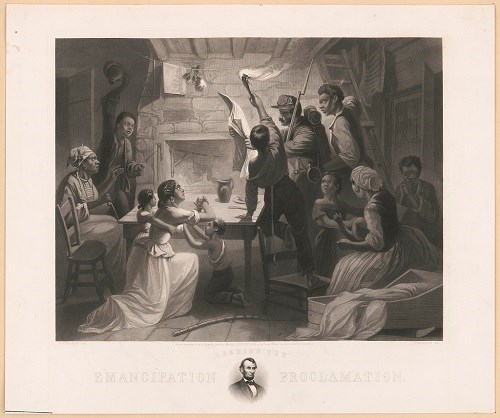

Library of Congress There are plenty of examples of Lincoln’s great talent as an author. Lincoln often thought about large concepts and ideas for his speeches and writings. He would run through these ideas over and over again, in his mind and on paper, sometimes over the period of many months. This means that there are gems of literary eloquence to be found in even his lesser-known addresses and letters. First Inaugural AddressAt the time of the First Inaugural Address on March 4, 1861, the nation was on the verge of civil war. When Lincoln arrived in Washington, DC, seven southern states had already seceded from the Union. No president had ever delivered an inaugural address during such uncertainty and tumult. Lincoln appealed to the sensibilities of the country when he said, “In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war. The government will not assail you. You can have no conflict without yourselves being the aggressors.” Lincoln concluded by reminding us of our connections when he very poetically said, “We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battle-field, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearthstone, all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.” Annual Address to CongressThe president submitted this address in December of 1862, one month before he signed the Emancipation Proclamation into law. Lincoln masterfully articulated his belief that the abolition of slavery was more than morally the right thing to do. It was critical to the survival of the nation and of democracy in the world. It is often considered his finest message to Congress, and perhaps the finest such message by any president. It showcases Lincoln's eloquence while directly and honestly assessing the multitude of problems the country was facing. This is the poetic conclusion to his nearly 8400-word address: “The dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate to the stormy present. The occasion is piled high with difficulty, and we must rise with the occasion. As our case is new, so we must think anew, and act anew. We must disenthrall ourselves, and then we shall save our country.Fellow-citizens, we cannot escape history. We of this Congress and this administration, will be remembered in spite of ourselves. No personal significance, or insignificance, can spare one or another of us. The fiery trial through which we pass, will light us down, in honor or dishonor, to the latest generation.

NPS Photo/Adams Gettysburg AddressOn November 18, 1863, Lincoln traveled to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. The next day, he delivered "a few appropriate remarks" at the dedication ceremony for one of the country's first national military cemeteries. Gettysburg had been the site of a three-day battle in July of that year. The Union victory there became a turning point in the Civil War. That victory came at a heavy cost, with more than 50,000 Union and Confederate soldiers killed, wounded, or missing. Lincoln's speech, remarkable for its brevity at only 272 words, helped the nation make sense of the loss of life throughout the war. The president also framed the purpose of the war for the struggle still to come. Today, this speech is a reminder of the sacrifices made for the benefit of our freedoms and for the preservation of American democracy. The Gettysburg Address has become one of the most famous speeches in world history. Lincoln's words are prose that read like poetry, penned by our eloquent president. Lincoln goes back in time to the Declaration of Independence, signed “four score and seven [87] years” before he gave this speech. He saw this founding document as defining the United States' national values. Lincoln summarizes those core ideals as liberty and equality for all. Lincoln says that the United States is unique. No country had ever been founded on such high ideals of democracy, liberty, and equality. He says that the Civil War is a test of whether this nation, based on these standards, could possibly survive. Lincoln uses this moment to help the country make sense of the severe loss of life. Why did so many have to die? It must be to allow so many others to gain their freedom. These brave soldiers died to protect American democracy. They also gave their lives to provide permanent emancipation for the four million enslaved people throughout the nation. Lincoln is attempting to give proper tribute to those who perished. He says that their actions speak louder than his words ever could. It is ironic, then, that Lincoln’s words from Gettysburg have been so well-remembered. Within a month of giving the Gettysburg Address, school children were memorizing the speech. Today, these words stand forever etched in Indiana limestone on the south wall of the Lincoln Memorial. In the end, the Union won the Civil War and slavery was abolished. As Lincoln said, the nation underwent a “new birth of freedom” based in those shared national values. However, he also correctly anticipated that there would still be more to do. The United States had to continue working to reach a point of true liberty and equality for everyone. It would be up to all generations to make sure that the United States remains a nation “dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” To ensure that this government of, by, and for the people “shall not perish from the earth”. Lincoln challenged us. He said that this “unfinished work” is the “great task remaining” for every generation.

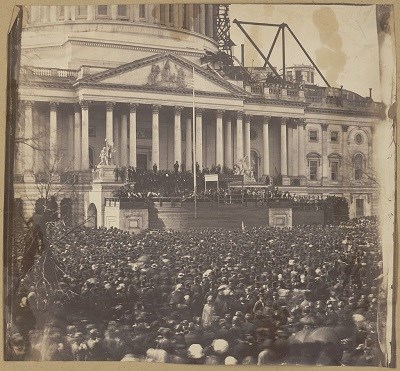

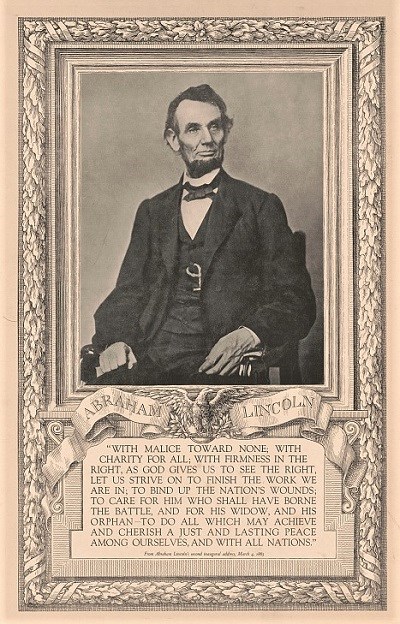

Library of Congress Historian James McPherson wrote that “more than perhaps any other president, Lincoln led and persuaded through the words of his speeches and writings.” Lincoln's words moved people, both then and now. They reflect his intellect and his creativity. They show his firm grasp of the critical issues of the time. They demonstrate his evolving understanding of the meaning and purpose of the war and of his nation. Second Inaugural AddressWhen Lincoln gave his Second Inaugural Address on March 4, 1865, the brutal four years of civil war were coming to a close. The reelected president wanted to unify a broken nation. Anger still persisted across the lines of North and South. Lincoln did not place blame or rejoice in the sanctity of the Federal cause. Lincoln instead offered conciliatory words to citizens on all sides. The address offered a blueprint for what Reconstruction might have looked like. Sadly, Lincoln was assassinated six weeks after he spoke these words: "Fondly do we hope—fervently do we pray—that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue, until all the wealth piled by the bond-man's two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said, 'The judgments of the Lord, are true and righteous altogether.' Want to Learn More?

|

Last updated: August 14, 2025