Howard University While living in the White House, Mary Lincoln formed several friendships. Perhaps her most notable connection was one with a formerly enslaved woman, Elizabeth Keckly (also sometimes spelled Keckley). Elizabeth Keckly’s life was an incredible story of perseverance and survival. It started in the direst of conditions and ultimately involved and influenced some of the most powerful Americans of the day. In February 1818 in Dinwiddie County, Virginia, an enslaved woman named Agnes (“Aggy”) gave birth to a daughter, Elizabeth. Elizabeth’s father was their enslaver, Colonel Armistead Burwell. Agnes had no choice or power in the "relationship." Since her mother was enslaved, Elizabeth ("Lizzy)" was born into slavery as well. Not initially aware of the identity of her biological father, Lizzy grew up believing him to be Agnes’ later husband, George Hobbs. Hobbs was an enslaved man who lived nearby and with whom she had a close relationship. Growing up on the Burwell plantation, Elizabeth worked with her mother on tasks like taking care of the Burwell children. Agnes also sewed for the family and taught this skill to her daughter, along with how to read and write. Living on the Burwell plantation, Elizabeth saw the horrors of slavery firsthand. Lashings and other punishments were all too common. She also experienced heartbreak when George Hobbs’ enslaver took him out west, away from the family. They never saw him again. Sadly, Elizabeth experienced further heartbreak when the Burwells separated her from her mother at the age of 14. The Burwells sent her to work for their son, Reverend Robert Burwell, and his wife Margaret in North Carolina. At Robert Burwell’s home, she continued to experience the horrors of slavery. Robert, his wife, and their neighbor beat Elizabeth frequently. They then gave her to work for a local store owner, Alexander McKenzie Kirkland. Kirkland repeatedly assaulted her over the next four years. In 1839, she gave birth to a son by him that she named George after her assumed father, George Hobbs. After ten years surviving these horrors, Elizabeth and her son George returned to Virginia when Armistead Burwell died. Burwell’s son-in-law, Hugh A. Garland inherited them as property following Armistead’s death. Hugh Garland had married Elizabeth's white half-sister, Ann. The Garlands moved to St. Louis in 1847 and brought Agnes, Elizabeth, and young George with them. Hugh Garland continued his law practice in Missouri. His most famous case was serving as the defense attorney for John Sanford. Sanford was the enslaver of Dred Scott, an enslaved man who became famous for seeking his freedom before the Supreme Court. While living in St. Louis, Elizabeth became an accomplished seamstress. Her wages constituted a major income source for the Garlands, who were increasingly unable to support themselves without her.

University of Delaware Special Collections Over the next several years, Elizabeth became highly successful and mingled with the free Black population of St. Louis. In 1850, she met James Keckly, a free African American man, and they developed a relationship. She refused to marry him until she and her son were free, and asked Hugh Garland for her freedom. At first, Garland refused. He later agreed to free her at the cost of $1200 for her and her son. With this hope of independence, Elizabeth married James Keckly in 1852. Elizabeth Keckly worked to raise the money to secure her freedom for the next three years. The Garlands made this effort difficult with their constant demands, making it difficult for her to earn money of her own. In the end, Mrs. Keckly's connections she had made in St. Louis stepped up. The sympathetic Le Bourgois family came to her aid, giving her money which served as a loan to purchase her freedom. In this way, Elizabeth Keckly finally achieved freedom for herself and her son in 1855. She remained in St. Louis, continued her work as a seamstress, and became a successful dressmaker. By 1860, she had repaid the loans to the Le Bourgois family. She also separated from her husband because of his abuse of alcohol that, she noted, made him “a burden instead of helpmate.”

Library of Congress On Inauguration Day, March 4, 1861, Mary Lincoln was growing desperate looking for a dress for an upcoming party. An acquaintance of Mary, Margaret Sumner McLean, recommended Elizabeth Keckly to her. Mary interviewed Elizabeth Keckly, became impressed with her work, and entrusted her to make the dress. On the day of the party, Elizabeth returned with the dress to an upset Mary, who was concerned that she would be late for the reception. Elizabeth calmed her and convinced her to wear the dress. After putting it on, President Abraham Lincoln entered the room and, declared upon seeing her: “You look charming in that dress. Mrs. Keckly has met with great success.” Mary went on to hire Elizabeth as her personal modiste (dressmaker). Over the next four years, Elizabeth Keckly made many dresses for Mary Lincoln. The two women also grew close after the deaths of their sons. George Keckly enlisted in the Union army (as he passed for a white man) and died at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek on August 10, 1861. Mary helped comfort Elizabeth after his death. Six months later, Willie Lincoln died in the White House, likely from typhoid fever. Elizabeth helped Mary through this difficult time and accompanied her on her trips to New York City.

National Museum of American History Elizabeth Keckly also helped many self-emancipated people who entered Washington, DC to seek their freedom. To assist them, she founded the Contraband Relief Association. This organization helped the many camps of escaped enslaved people scattered throughout the city. Abraham and Mary Lincoln helped her in these efforts by donating money to the relief organization. She also met with many prominent abolitionists, including Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth. Keckly arranged a meeting between Sojourner Truth and Abraham Lincoln in 1864. On the evening of April 14, 1865, Elizabeth Keckly learned that Abraham Lincoln had been shot at Ford's Theatre. She immediately rushed to the White House. The soldiers guarding the White House refused her entry and provided her little information. Mary, a few blocks east in the city, asked for Mrs. Keckly to come to the Petersen Boarding House. Three messengers went looking for her, but all went to the wrong address. Elizabeth returned to the White House the following morning to a grieving Mary who asked her, "Why did you not come to me last night, Elizabeth -- I sent for you?" Keckly responded, "I did try to come to you, but I could not find you."

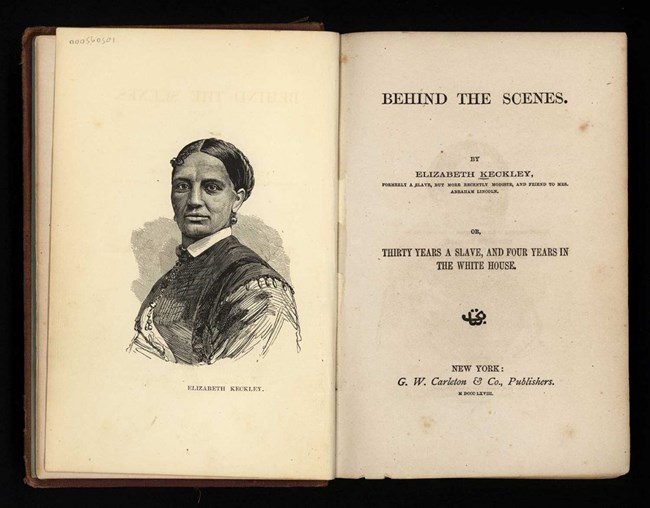

Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection Over the next two years, Elizabeth Keckly remained an important part of Mary Lincoln’s life. She accompanied Mary to Chicago on the funeral train, helping to comfort her during this difficult time. By 1867, Elizabeth Keckly had returned to Washington, DC when Mary Lincoln again asked for her help in New York City. Following President Lincoln’s death, Mary fell into substantial debt. She asked Mrs. Keckly to help her raise some money by selling some of her possessions. Keckly aided her in this effort, but it ended in scandal. The media criticized Mary for going against Victorian principles by selling her wardrobe and other items. To help Mary, Elizabeth Keckly also wrote to other prominent African American leaders, including Frederick Douglass, to raise money. She also placed some of Abraham Lincoln’s possessions on a tour to help raise more funds. Unfortunately, Mary had not agreed to this exhibition and became upset by it. Their friendship began to sour. In 1868, Elizabeth Keckly decided to write about her life and her side of the story in an autobiography. She titled it Behind the Scenes, Or, Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House. In this autobiography, Keckly covered her enslaved life and the years she spent in the White House. She immediately faced criticism. The media criticized the book for going into intimate details of her friendship with Mary Lincoln, arguing that it violated the norms of society. Mary Lincoln expressed her anger about the book, as it included the dress-selling scandal. Keckly explained in the preface that she was trying to show Mary in a sympathetic light, but to no avail. The two never spoke again. Robert Lincoln, embarrassed by the scandal, used his influence to halt publication of the book, and few copies were sold. The book’s scandal damaged Elizabeth Keckly’s reputation, and she lost many of her clients.

NPS Photo/Byers Despite these challenges, Elizabeth Keckly continued to work as dressmaker for decades. In 1892, she accepted a faculty position at Wilberforce University in Ohio as head of the Department of Sewing and Domestic Science Arts. After a stroke the following year, she resigned and returned to Washington, DC. She lived her remaining years at the National Home for Destitute Colored Women and Children, which she had helped to found years earlier. Elizabeth Keckly died on May 26, 1907. She was buried in Columbian Harmony Cemetery in the District of Columbia. When Columbian Harmony closed in 1959, all of the remains, including Keckly’s, were moved to National Harmony Memorial Park in Landover Maryland. Elizabeth Keckly's new grave was unmarked until 2010. That year, a new bronze and granite marker was placed and dedicated to the memory of this remarkable woman. Want to Learn More?

|

Last updated: November 26, 2024