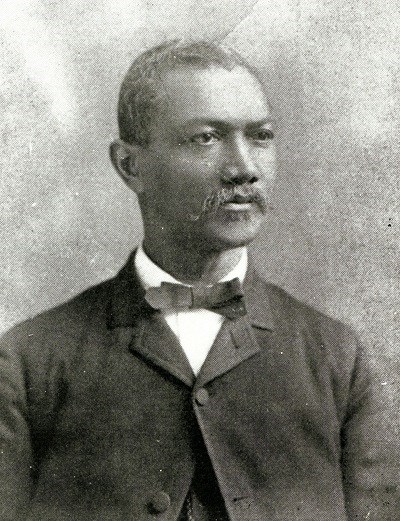

Alexander Thomas Augusta was born to free parents of color in Norfolk, Virginia on March 9, 1825. From his very first memories, he wanted to become a doctor. He spent his early years working towards that goal, something that was not easy for a Black man in the 19th Century. Despite state laws prohibiting the education of Blacks, Augusta learned to read and write. As a young adult he moved to Baltimore, and then to Philadelphia, where he hoped to enroll into the University of Pennsylvania’s medical school. Throughout these transitions, he supported himself by working as a barber. Augusta was denied entrance to the university due to what he called a “prejudice of color.” Because of laws preventing the education of Blacks, he would have lacked the evidence needed to prove that he had the prerequisites for admittance. This was likely another factor for his rejection. Undaunted, Augusta was able to convince a professor who was sympathetic to his cause, to secretly tutor him. Ultimately, Augusta moved back to Baltimore where he married Mary O. Burgoin, a woman of color. It is not certain whether she was Black, Native American or Mulatto, and there are no known images of her. She was listed as “coloured” in one Canadian census, and was noted as being a Native American in two historical accounts. The two would enjoy a strong partnership that endured to the end of Alexander’s life. At some point thereafter, the newlyweds moved to California. Based on the timing of their move west, it is believed that they, like many others, went with hopes of striking it rich in the California gold rush. The 1852 census lists Augusta as a barber in El Dorado County, CA, which was “the heart of the gold country.”

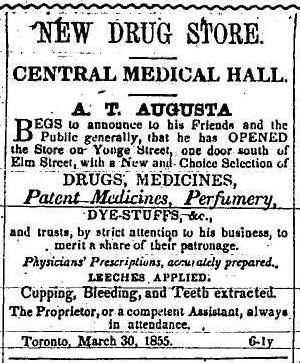

City of Toronto Archives Mary matched her husband’s drive by becoming one of just a few women of color who owned and operated a business. She called it the “New Fancy Dry Goods and Dress Making Establishment.” Her business was located in Toronto’s first working-class suburb, an area that attracted many newcomers, including a large population of formerly enslaved people. She also advertised in the “Provincial Freeman” newspaper that was “committed to ending discrimination and encouraged opportunities and education”, particularly for those who had recently arrived in Canada. This connection makes it likely that Mary, just like her husband, wanted to support her community, and people like themselves who were looking for a chance to succeed.

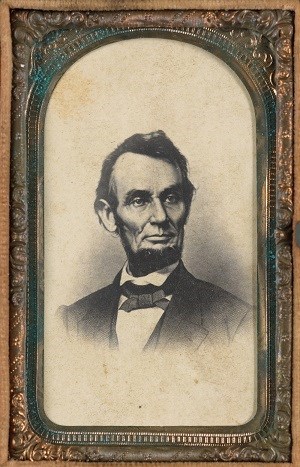

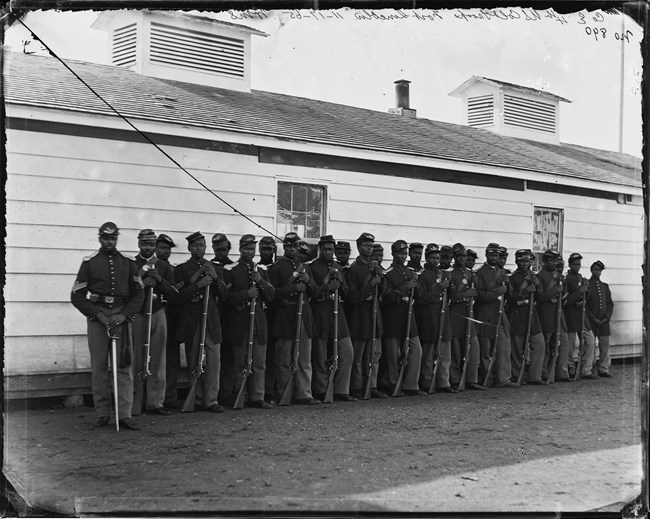

City of Toronto Archives During his time in Toronto, Augusta was an active member of the community, taking a special interest in helping other Blacks. He was president of the Association for the Education of Colored People of Canada. He also spoke out against racial injustices, placing actions to his words. He drafted a resolution for the Canadian Parliament opposing an anti-Black candidate, and decided to leave his all-Black church as a way to protest the segregated institutions that existed throughout Toronto. Despite his deepening roots in Canada, Augusta kept one eye on his home country as it moved into a Civil War. Augusta was stirred into action when the Emancipation Proclamation was signed by President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863. This historic document called for the freedom of enslaved people in the Confederate states. It also allowed for the recruitment of Blacks to the Union Army. Augusta believed that “the coloured people have a duty to perform at this present time” so he wrote to President Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, on January 7, to offer his services to one of the Black regiments in the Union army. He requested “an appointment as surgeon to some of the coloured regiments, or as a physician to some of the depots of freedman.”

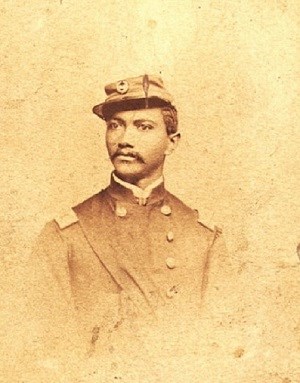

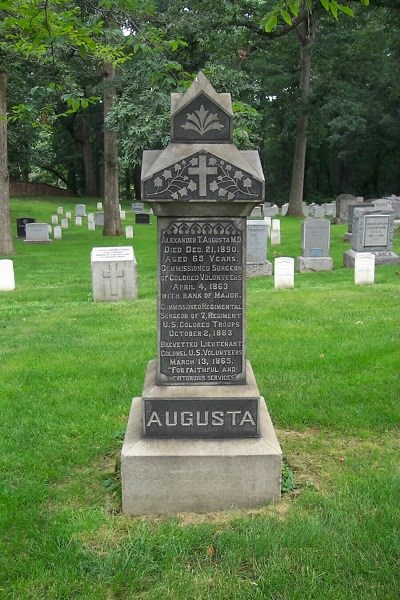

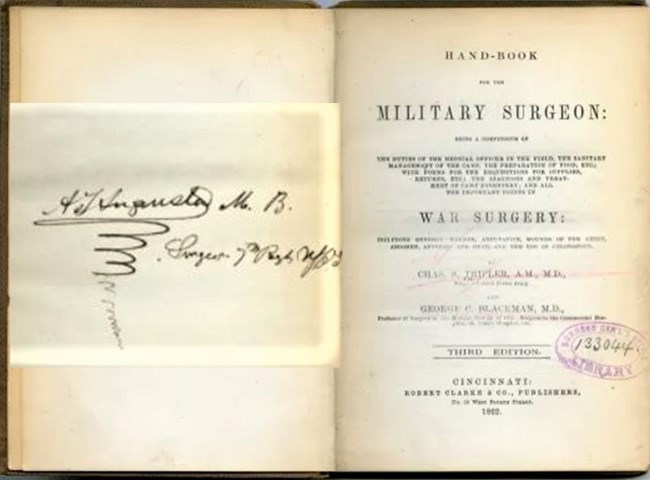

Library of Congress However, trouble commenced upon his return to the United States. Two days before his exam with the U.S. Surgeon General, Augusta received a letter claiming that there had been a mistake. His invitation to join the army was being “recalled” due to the fact that Augusta was a “person of colour.” The letter also stated that his military service would violate Great Britain’s proclamation of neutrality; that his ten years spent living in British North America technically made him a British subject. Alexander fought back and again wrote to President Lincoln, and members of the army’s medical board: “I have come nearly a thousand miles at great expense and sacrifice, hoping to be of some use to the country and to my race at this eventful period.” He mentioned that the rate of death from illness and disease among black servicemen was nearly twice as high as their white counterparts, thus the need for more medical staff in the field. On April 1, the Medical Board changed its stance and recommended that he be appointed as a surgeon for one of the black regiments. On April 14, 1863, at age 38, Augusta was commissioned as a surgeon with the rank of Major in the Union Army with the 7th U.S. Colored Infantry. He was the first of eight Black doctors to hold a commission in the Union Army.

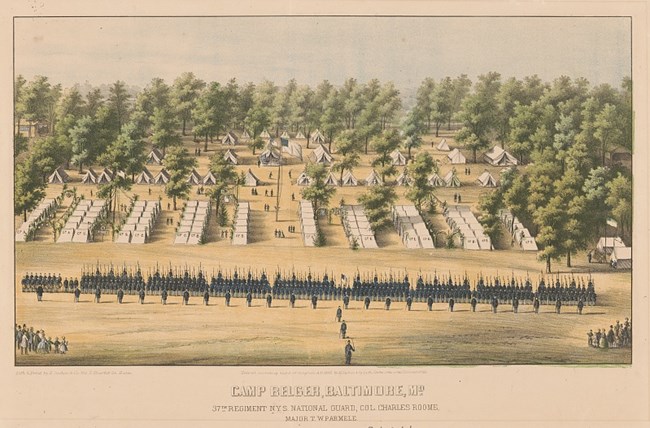

Oblate Sisters of Providence Not everyone wanted Augusta relocated. One White officer wrote in his defense that “surgeon Augusta has worked indefatigably while at Camp Stanton.” Ultimately, the War Department didn’t want to upset the physicians that were so difficult to recruit to the war efforts, and Augusta was transferred. In this move, he made history again. Augusta was placed in charge of a newly created hospital for African Americans at the site of Camp Barker in Washington, DC, making him the first African American to serve as the head of a hospital in the United States. His stay at Camp Barker was brief. He would hold this position until the spring of 1864 when he was reassigned to Camp Belger in Baltimore. Here, he would lead the urgent need of examining newly enlisted Black soldiers.

Library of Congress As he had so often done, Augusta forged ahead and wrote a letter to the judge advocate in DC, with a full account of what had happened. This was forwarded to Senator Charles Sumner (MA) who was sponsoring a law to prohibit street car companies in the nation’s capital from segregating passengers due to race. Sumner, who was a fierce and renown abolitionist, took the story to the floor of the Senate. He made it clear to all that “an officer of the United States with the commission of major, with the uniform of the United States, has been pushed off one of these cars on Pennsylvania Avenue by the conductor for no other offense than that he was black.” Sumner argued that this incident “is worse for our country at this moment than a defeat in battle.” It would take another year, but in March 1865 legislation was passed that made streetcar discrimination illegal. In another battle against inequities faced by Blacks, Augusta took on the disparity in military pay between White and Black soldiers. During this time, all enlisted men of color were paid $7 a month, the standard wage for a Black private. White privates received $13 a month. As a commissioned officer, Augusta was initially salaried at $169 per month, the compensation of an army surgeon holding the rank of major. But this changed in early 1864 when the Army paymaster “refused to pay him more than seven dollars per month.” Augusta rejected this indignation.

Library of Congress Augusta’s lifelong efforts ultimately earned him the attention and respect of the military leadership. At the close of the war, he was awarded an honorary brevet rank of lieutenant colonel. This prestigious distinction made Augusta the highest-ranking Black officer in the U.S. Military, at that time. It was around this period when Augusta became one of the first African Americans to visit the White House. Augusta and his assistant, Dr. Anderson Abbott, were invited by President and First Lady Lincoln to attend a reception on February 23, 1865.

Library of Congress The Washington Chronicle reported their presence at the event stating the two men were “of genteel exteriors and with the manners of the gentleman.” The story was reprinted in newspapers across the country which is believed to have perpetuated the improved reporting of African Americans of rank. In just a few months, Abbott would be one of the attending physicians at the deathbed of President Lincoln, after he was shot by an assassin at Ford’s Theatre on the night of April 14, 1865.

Howard University In 1869, he was hired by the newly formed Medical College at Howard University, becoming the first black medical professor in the country. Some of his subject areas included "Practical Anatomy," "Descriptive and Surgical Anatomy," and “Diseases of the Skin." Augusta embodied the rapid change in the country during the Civil War and Reconstruction Era. A mere 20 years before he became the first African American to teach medical science at the college level, he was denied access to an education. When Augusta was denied membership to the Medical Association of the District of Columbia, he helped create the National Medical Society. The NMS opened membership to all physicians, regardless of race, and still operates today under the same founding principles.

Arlington National Cemetery It is not known exactly what happened to Mary. There is evidence that the years after her husband died were difficult. She applied for a military pension in 1891, and was listed in the 1900 U.S. Census for Baltimore, living in the St. Francis convent, a religious residence for orphans and the poor. She would have been 75 years old. What is known is that both Mary and Alexander Augusta supported one another, and used their own circumstances to help other people of color improve their conditions. His friend and fellow Union Army surgeon, Dr. Abbott, paid him this compliment, observing that Alexander Augusta, “stirred the faintest heart to faith in the new destiny of the race.”

|

Last updated: February 28, 2021