Library of Congress The history of Ford’s Theatre doesn’t end there. The murder of a beloved president launched a fascinating evolution of thinking over the subsequent decades. Americans considered and reconsidered the importance of preservation, memorialization, and how to best remember all facets of our past, both the good and the bad. This progression of our national consciousness aligns, in many ways, with the history of Ford’s Theatre.

Ford's Theatre Collection, FOTH 5008 Timeline of Ford’s Theatre, from 1834 to Today

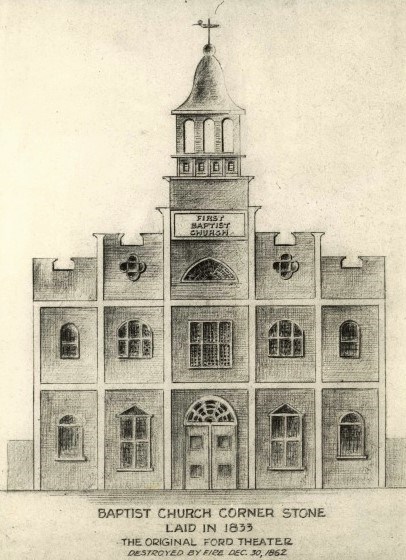

Library of Congress Not everyone was enthusiastic about the new theatre in town. Many residents did not think highly of the transient crews and actors associated with local theatres, considering them lewd and raucous. This sentiment was reflected by a member of the First Baptist Church, who predicted a “dire fate for anyone who turned the former house of worship into a theatre.” March 19, 1862: John T. Ford opened the doors to the “Ford’s Athenaeum," welcoming his first guests to the show The French Spy. December 30, 1862: A fire caused by a faulty gas meter destroyed Ford’s Athenaeum. Undaunted, John T. Ford rebuilt, increasing the size and grandeur of the building.

Library of Congress April 9, 1865: Union General Ulysses S. Grant accepted the surrender of Confederate forces under Robert E. Lee at Appomattox Court House, VA. April 9 – April 14, 1865: Most of the nation celebrated what was perceived to be the beginning of the end of the brutal four-year Civil War. April 14, 1865, 10:15pm: President Abraham Lincoln was shot while watching the play Our American Cousin. His assassin was John Wilkes Booth, a Confederate sympathizer and racist, who despised Lincoln for his efforts at ending slavery and granting citizenship rights to freed slaves. The unconscious president was carried across the street to the Petersen Boarding House. April 15, 1865, 7:22am: President Lincoln died from a single bullet wound to the head. April 15 – July 1865: Secretary of War Edwin Stanton seized control of Ford’s Theatre, now a crime scene. He placed guards around the theatre and limited access to the building as the murder investigation unfolded. Public outcry and grief in the wake of Lincoln’s death prompted closures of other theatres throughout the city. Mathew Brady’s photography studio was permitted to take crime scene photos of the interior of Ford’s Theatre. Almost a century later, these images became invaluable when the theatre was restored. The War Department’s control of the building during this time marked the beginning of federal management of Ford’s Theatre. Ford’s Theatre remained closed throughout the trial of Booth’s conspirators. A national debate played out over the future of Ford’s Theatre. Should the building be destroyed? Should a suitable memorial be established in its location? Or should Ford’s Theatre continue operations as a site for live performances? July 6, 1865: John T. Ford announced the reopening of the theatre via newspapers in Washington, DC. The performance scheduled for July 10 was planned as a benefit for the Lincoln National Monument Fund. He sold over 200 tickets to The Octoroon, the play that had been scheduled to run on April 15. Stanton and the War Department opposed the reopening of Ford’s Theatre. July 10, 1865: The night of the first performance scheduled at Ford’s Theatre since the assassination. From an account published in The Sun about the events of that night: “…an order was issued from the War Department on Monday afternoon directing the building to be closed; and about half-past 5 o’clock in the evening Capt. Peabody, with a detachment of about thirty men, appeared on the ground, and took possession of the building, placing guards at all the entrances of the same, and notifying the manager that he would not be allowed to open the theatre for the present. Shortly afterwards a large poster (bearing the words, “Washington, July 10 – Closed by order of the War Department”) was placed upon the door of the theatre. At about 7 o’clock, the hour at which it was announced the doors would be opened, numbers began to flock towards the theatre, the majority of whom, after pausing a few moments on the pavement in front of the building, quietly took their departure. Parties continued to linger about the building as late as 9 o’clock, but there were no riotous demonstrations manifested. In anticipation that some disturbance might occur, General Augur, commanding this department, instructed Captain Hill, who has charge of the “provisional cavalry” stationed in the city, to hold himself in readiness for service at a moment’s notice. All, however, passed off quietly, and at 10 o’clock the guard having charge of the theatre was greatly reduced.” July 12, 1865: The New York Herald voiced the concerns that were being echoed around the country. It said that allowing performances to continue at Ford’s Theatre was “a violation of the public sense of propriety… an attempt to coin the blood of a great man.” July 1865: The Cabinet of President Andrew Johnson discussed the ethics of seizing private property that deprived an individual from earning an income. Did the federal government have the right to stop performances at Ford’s Theatre, thus preventing John T. Ford from earning his livelihood? Ford threatened legal action as the War Department continued to prevent the operation of the theatre. The federal government began leasing the building for $1,500 per month.

Library of Congress Fall 1865: Although Congress had not formally approved funding to purchase the building, the government continued to dismantle the interior of Ford’s Theatre, making it unsuitable for plays and other entertainment. By now, the very theatre interior that had been the center of a national dialogue on how to commemorate the murder of a president was completely gone. The removal of the interior at Ford’s Theatre quieted memorial discussions surrounding the site. The theatre was now completely under government control, with updates on its progress reported by newspapers around the country. The New York Herald wrote that “large number of strangers visit Ford’s theatre every day, but the place has been so entirely changed that there is little gratification to be obtained.” November 1865: The construction project was completed. The interior demolition of the theatre allowed for the building to be converted into three floors. The structure still maintained the original four exterior walls and front facade, all present on the night of the assassination. These silent witnesses to a national tragedy are still in place at Ford’s Theatre today. The War Department and the Army’s Surgeon General’s Office planned to move into the newly remodeled Ford’s Theatre building. April 1866: Congress approved appropriations for “the purchase of the property in Washington city, known as Ford’s Theatre, for the deposit and safe-keeping of documentary papers relating to the soldiers of the army of the United States, and of the museum of the medical and surgical department of the army…”

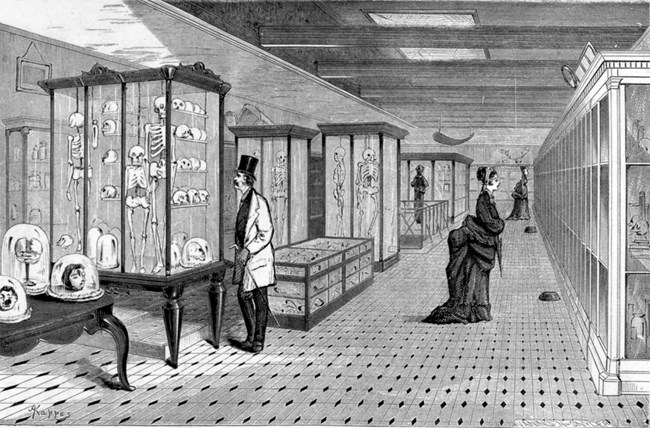

Library of Congress The United States Army Medical Museum, founded in 1862, began moving their collections from the Corcoran Building on H Street to the third floor of the former theatre. The new offices at Ford’s Theatre allowed space for the museum to showcase and archive the rapid changes that army medical services had experienced during the Civil War. Their efforts to create a medical reference book of the museum’s collection began prior to the move to 10th Street and continued in the new offices. The first and second floors were designated as offices for the Division of Records and Pensions, providing needed space for staff to work through the immense backlog of Civil War pension applications. December 1866: The Division of Records and Pensions relocated over 16,000 bound document groups and an accompanying library of 2,200 books. April 16, 1867: The US Army Medical Museum opened at Ford’s Theatre. The New Ford’s Building became active again with the traffic of a curious public. In its first year, the museum hosted 6,000 visitors.The museum was operated in tandem with what had become a work site for government employees. By 1870: The library of the Division of Records and Pensions had grown in size to 10,000 books, an increase from its initial inventory of 2,200 volumes. By 1874: The former Ford’s Theatre, then referred to as the New Ford’s Building, served as the workplace of 134 clerks, an anatomist, an engineer, a messenger, and 22 employees who served as either “laborers or guards.” 1870 to 1880: The US Army Medical Museum published the Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion from the New Ford’s Building. Eerily, a piece of John Wilkes Booth’s spine was displayed in the museum in the New Ford’s Building. By 1874: The US Army Medical Museum’s annual visitation exceeded 31,000 people. By 1881: The museum’s annual visitation had grown to over 40,000. 1880s: Displays at the US Army Medical Museum allowed visitors to examine the remains of both Union and Confederate soldiers. The authenticity and stark reality of these exhibits enabled visitors to contemplate the meaning and purpose of the Civil War, and the legacy of Abraham Lincoln, some 20 years later. 1887: The US Army Medical Museum leaves the New Ford's Building, moving to a new brick building on the National Mall. The museum moved several times over the ensuing decades and was dispersed in 1969. The National Museum of Health and Medicine, located in Silver Spring, Maryland, now holds the majority of the old Army Medical Museum collection. By 1892: John T. Ford’s theatre had been transformed into a multi-level structure with an interior that bore no resemblance to the elegant 1865 space that had hosted a president. Yet, despite the fact that 27 years had passed, people came to the site because it was where Abraham Lincoln had been assassinated. Employees in the building were able to point out the general location of the state box to curious visitors and to provide them with the details of that terrible night.

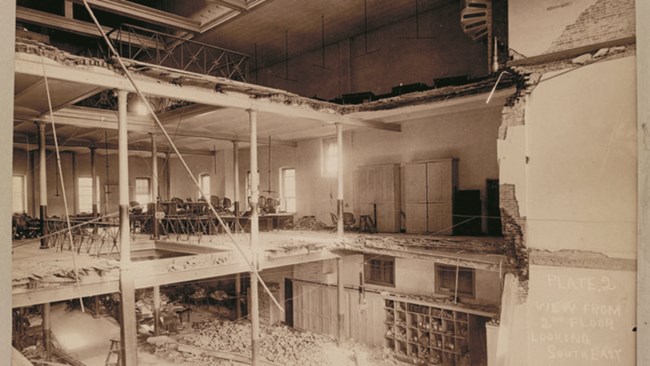

Library of Congress In addition to the outcry from the public over the causes of this disastrous event, there was concern over the loss of important pension records. By this time, the Division of Records and Pensions was responsible for original Civil War medical records. Its workers were in the process of generating references that would help to expedite pension claims and requests for records of military service. December 1893: Repairs to the old Ford's Theatre building were completed. It remained a storehouse for various records and publications until 1931. However, after much discussion, most of the staff from the Division of Records and Pensions were relocated. 1893: The Petersen Boarding House, where Abraham Lincoln died, became an open-to-the-public site for the first time. It was transformed into a museum through an agreement with the Memorial Association of the District of Columbia and amateur Lincoln historian Osborn H. Oldroyd. This provided Oldroyd with the perfect place to showcase his large collection of Lincoln artifacts. 1896: The federal government purchased the Petersen Boarding House, located across the street from Ford’s Theatre. Oldroyd continued operating his museum here. Prior to his death in 1930, Congress purchased his collection of Lincolniana. Oldroyd's artifacts remain part of the Ford's Theatre National Historic Site museum collection today. Late-1920s: Congress shifted management of the Ford’s New Building warehouse and the Petersen House (also referred to as “The House Where Lincoln Died”) from the War Department to the Office of Public Buildings and Public Parks. 1927: During this period of management transition, Representative Henry Riggs Rathbone revived the 1865 discussions around creating a national memorial at Ford’s Theatre. Rathbone was the son of Major Henry Rathbone and Clara Harris, the couple that was in the state box with the Lincolns on the night of the assassination. He presented a “Bill to Establish a National War Memorial Museum and Veteran’s Headquarters in the Building Known as Ford’s Theater [sic]” to the 69th Congress. Representative Rathbone continued to lobby for the idea of a museum at Ford’s Theatre until he died in 1928. By 1931: Although Rathbone’s bill never passed, the public dialogue that it generated, and the transfer of the building to the Office of Public Buildings and Public Parks, created a path for Ford’s Theatre to become a museum. In addition, there were concerns regarding the fire safety of the Petersen House and whether it was an appropriate place to display the Lincolniana. All of this contributed to the development of an exhibit space on the first floor of Ford’s Theatre. By 1932: The role of the National Park Service (NPS) changed. Its important mission of conserving and protecting America’s most significant natural areas now also included the protection and management of the nation's historic sites.

Library of Congress 1933: This new NPS era of management was made official with the Executive Order of 1933. This order placed federally-owned historic sites, like Ford’s Theatre and the Petersen House, under the direction of the NPS. 1933 – 1939: The NPS staff for the Lincoln Museum learned that some of the artifacts most crucial to telling the assassination story were under the jurisdiction of the War Department. Included were some of the key items entered as evidence in the Lincoln conspirators’ trial, like the Deringer pistol Booth used to kill Lincoln, the bullet with which Lincoln was shot, the dagger Booth used to attack Major Rathbone, a boot worn by Booth during the assassination, Booth’s diary, the doctor's probe, and pieces of Lincoln's skull. These important historical artifacts were held in the basement of the State Department building. The NPS requested that they be transferred into its collection for possible public display. 1936: With the Lincoln Museum occupying only the first floor, the second and third floors of Ford’s Theatre remained vacant. To fill this space, the Eastern Museum Laboratory, an exhibit-building workshop, was relocated from Morristown, NJ. Dioramas, exhibits, topographic maps, and other three-dimensional exhibits were built at Ford’s Theatre for NPS sites such as Fredericksburg, Morristown, Fort Frederick, the Gateway Arch, and the Department of the Interior Museum. 1939 – 1940: The War Department relinquished a group of artifacts to the Lincoln Museum on an indefinite loan, with the expectation that they would be placed on display. However, this treasure trove of high-quality pieces launched a debate around the ethics of how to interpret the assassination. Some of the items were deemed as too inappropriate to display and were not included in the exhibits. Those items included the Deringer pistol, pieces of the president's skull, and the doctor's probe. 1941 – 1945: During World War II, historic cannons and other artillery from various locations were stored in the basement of Ford’s Theatre. This provided a space to protect these artifacts from the threat of meltdown during the scrap drives that occurred throughout the war.

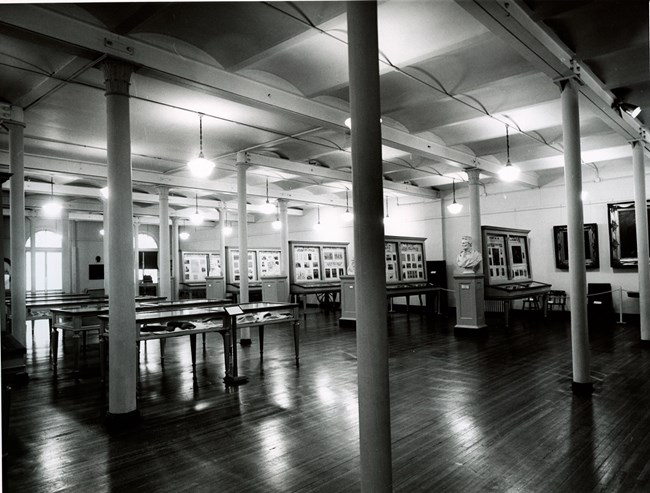

NPS Ford's Theatre Collection, FOTH 3224 From 1932 – the 1950s: Visitors to the Lincoln Museum wanted to see the interior as it appeared at Ford’s Theatre on the night of Lincoln’s assassination. However, it wasn’t until the 1950s that a restoration campaign began to gain support within Congress. 1946 – 1961: Senator Milton R. Young (R-North Dakota) publicly and tirelessly advocated for the restoration of Ford’s Theatre, introducing several bills to Congress over these 15 years. His voice was instrumental in the renovations that we enjoy today. Young proclaimed, “The restoration of the stage, the boxes, and the scenery in Ford’s Theater [sic] is a duty which should be carried by us all.” April 1947: The boots that Lincoln wore to his deathbed were donated to the NPS by schoolteacher Ruth Hatch of Lynn, MA. Hatch was the granddaughter of Justin H. Hatch, a friend of William Clark. It was Clark’s room in the Petersen Boarding House where Lincoln was taken after he was shot at Ford’s Theatre, and where he died 9 hours later. The boots were removed from Lincoln’s feet, then left in Clark’s room. Clark gave the boots to Hatch as collateral for a loan and never returned for them. The cherished pieces were oiled for preservation and placed on display that September. In 1950: The Lincoln Museum received over 112,000 visitors and the “House Where Lincoln Died” hosted over 52,000. By 1953: Annual attendance for the Lincoln Museum had increased to over 152,000. 1954: “Public Law 83-372” was passed by Congress, requiring the Department of the Interior to prepare studies to estimate the cost of restoring Ford’s Theatre to its state on the night of Lincoln’s assassination. 1964: Congress approved over $2 million to restore Ford’s Theatre to its April 14, 1865 appearance.

Ford's Theatre Museum Collection November 29, 1964: Ford’s Theatre closed its doors to the public in preparation for construction and restoration. At that time, it was projected to re-open in late-1966. The “House Where Lincoln Died” continued to operate during the closure of the Theatre. May, 1965: Secretary of the Interior Stewart L. Udall approved changes in the reconstruction plans of Ford’s Theatre to allow for live theatre performances, and for the accommodation of about 600 patrons. He preferred that the productions would focus on “Lincoln’s historical time in Washington,” but he gave his approval without a set plan for the type of live theatre. NPS leadership realized that they would need help implementing live theatre performances. June 1967: The Ford’s Theatre Society was founded, partnering with the NPS to run the theatre, hire the theatre company, and help raise additional funds. January 30, 1968: Ford’s Theatre reopened as a working, live theatre, 103 years after its lights had gone dark. Actress Helen Hayes led off the nationally-televised celebratory event, marking the start of Ford’s Theatre serving as a living memorial to the legacy of Abraham Lincoln.

NPS Photo 1970: Ford’s Theatre, the Star Saloon, and the Petersen House were combined and named the “Ford’s Theatre National Historic Site.” This site remains administered by the NPS to this day. April 10, 1975: President Gerald R. Ford became the first president to visit Ford's Theatre since the assassination of President Lincoln. He attended actor James Whitmore's performance in Give 'Em Hell, Harry, a one-man show about the life of President Harry Truman. Every president since then has visited Ford's Theatre. In the 1970s and 1980s: The focus of interpretation shifted again. The 1981 museum plan proposed a “total rehab of exhibits to shift emphasis from Lincoln’s career to the events surrounding the assassination.” This was a radical departure from the approach of the mid-1960s, when the site deliberately deemphasized the assassination.

Library of Congress 1) Assassination and Aftermath 2) Temper of the Times 3) The Legacy of Lincoln 4) The History and Restoration of Ford’s Theatre. The site’s overall interpretive themes were listed as: 1) the Lincoln assassination and surrounding events 2) President Lincoln and the memorial concept 3) Washington, DC, 1865: the city and its environment in relation to the assassination. 1988: Extensive renovations took place at the Ford’s Theatre Museum. Booth’s pistol and a fragment of the fatal bullet were displayed prominently in the museum for the first time. New exhibits also addressed Lincoln’s funeral and the prosecution of Booth and his co-conspirators.

NPS Photo February 12, 2009: Ford's Theatre reopened on President Lincoln's birthday with a completely new museum layout. April 14-15, 2015: The National Park Service and the Ford's Theatre Society commemorated the 150th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln's assassination. Thousands of visitors attended the ceremonies to pay their respects to Lincoln. Today: Ford’s Theatre National Historic Site continues to interpret the events surrounding the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln and Lincoln's legacy. The building hosts regular theatre shows to carry on Lincoln's love of theatre. Our partners at the Ford’s Theatre Society produce live performances several times each year. For the current theatrical schedule, and for information on tickets visit the Ford's Theatre Society website. Ford’s Theatre National Historic Site is proud to welcome an average of 650,000 annual visitors from all around the world.

NPS Photo Want to Learn More?

|

Last updated: December 11, 2025