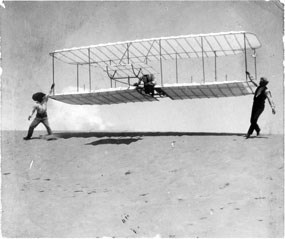

Wright State University Special Collections and Archives Where did the Wrights test their gliders and airplanes? The Wrights tested their earliest kites near their home in west Dayton. However, by studying the data of German aviation pioneer Otto Lilienthal, the Wrights found that they needed a headwind of fifteen to twenty miles per hour to launch their gliders. They also wanted privacy and sand dunes to cushion landings. They learned of Kitty Hawk, a remote community on the outer banks of North Carolina, by studying a table of average wind speeds compiled by the U.S. Weather Bureau. The Wrights tested their gliders and airplanes at Kitty Hawk from 1900 to 1903 and again in 1908. From 1904 to 1905, and again from 1910 to 1916, the Wrights tested their airplane designs at Huffman Prairie, a 100-acre (40 ha) pasture owned by Dayton banker, Torrence Huffman eight miles northeast of downtown Dayton. Orville and Wilbur wanted a testing ground that was closer to their home in Dayton than was Kitty Hawk. The Dayton-Springfield Pike and the Dayton, Springfield & Urbana Electric Railway bordered Huffman Prairie, and trolleys from Dayton arrived at nearby Simms Station every thirty minutes. The Wrights did not test their airplanes from 1906-1907 or during 1909.

Wright State University Special Collections and Archives Where is the 1903 Wright airplane? You may see the airplane that the Wrights flew on December 17, 1903 at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. Orville Wright gave the airplane to the Smithsonian in his will. From 1928 to 1948, the Science Museum in London displayed the airplane. Orville Wright refused to let the Smithsonian display the airplane since for many years a Smithsonian exhibit stated that Samuel Langley’s Aerodrome was the first craft capable of sustained, powered, controlled flight. Langley (1834-1906), the third Secretary of the Smithsonian, also tested his craft in December of 1903, but it failed its tests, falling from its launching craft into the Potomac River near Quantico, Virginia. In 1914, aviator Glenn Curtiss – against whom Orville filed lawsuits claiming patent infringements – flew a modified version of the Aerodrome, prompting the fourth Secretary of the Smithsonian, Charles Walcott, to assert Langley’s priority. The 1903 Wright airplane did not return to the United States until the Smithsonian withdrew its claim that the Aerodrome was the first airplane capable of flight. It made a statement that satisfied Orville in 1942, and the Smithsonian placed the 1903 airplane on exhibit on December 17, 1948 – after the end of the Second World War and after Orville’s death the previous January. Did inventing the airplane make the Wrights rich? Orville and Wilbur’s invention of the airplane brought them enough money to live comfortably. In 1912, Wilbur, Orville, and their sister Katharine together designed a large house in the Dayton suburb of Oakwood. Hawthorn Hill, as the house is known, cost $39,600 to build (equivalent to nearly $710,000 in 2002). Its construction ended in the spring of 1914, and Orville, Katharine, and their father Milton moved there from their longtime home in west Dayton (Wilbur died of typhoid fever in 1912). At his death in 1948, Orville left an estate worth $1,067,105.73, according to Montgomery County probate records. He left $300,000 to Oberlin College, where Katharine graduated in the class of 1898 and later served as a trustee; gave annuities to relatives and members of his household staff, and made small bequests to Berea College in Kentucky and Earlham College in Indiana. Dayton-based National Cash Register bought Hawthorn Hill and converted it into quarters for the company’s guests. In 2007, Hawthorn Hill was deeded back to the Wright family. How much did it cost to invent the airplane? Orville Wright recollected later in his life that inventing the airplane cost about $1,000 – or approximately $20,000 in 2002 dollars. He did not calculate the cost in time or personal energy invested. Interestingly, the U.S. War Department paid Smithsonian Institution Secretary Samuel Langley $50,000 in 1899 (nearly $1.07 million in 2002) to build one of his aerodromes for the military. Unfortunately, the aerodromes Langley delivered to the War Department never flew. What did Orville think about the military uses of airplanes, especially during the First (1914-1918) and Second (1939-1945) World Wars? Orville’s ideas on the military uses of airplanes evolved during his life. In October of 1917, six months after the United States entered the First World War on the side of the Allied Powers, Orville stated in Aerial Age that he believed that their capabilities for scouting made airplanes agents of peace. He wrote that the “nation with the most eyes will win the war and put an end to war.” Days before the armistice that ended the war in November of 1918, he wrote that the “aeroplane has made war so terrible that I do not believe any country will again care to start a war...” During the 1920s, Orville continued to assert that aviation’s potential for destruction made airplanes tools for peace. A 1923 address he wrote for radio broadcast stated that the “possibilities of the aeroplane for destruction by bomb and poison gas have been so increased since the last war that the mind is staggered in attempting to picture the horrors of the next one. The aeroplane, in forcing upon governments a realization of the possibilities for destruction, has actually become a powerful instrument for peace.” The Second World War changed Orville’s perception of the airplane as an instrument for peace. Shortly after two B-29 bombers dropped atomic weapons on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Orville wrote in a letter that he “once thought the aeroplane would end wars. I now wonder whether the aeroplane and the atomic bomb can do it. It seems that ambitious rulers will sacrifice the lives and property of all their people to gain a little personal fame.”

National Park Service Why did the Wrights have so many bicycle shops? From 1892 to 1908, the Wright Cycle Exchange/Wright Cycle Company operated in five different locations: 1005 West Third Street, 1034 West Third Street, 23 West Second Street, 22 South Williams Street, and 1127 West Third Street. Only the fourth shop (22 South Williams Street) is intact with its integrity in its original location. The Wrights did not own any of these buildings; instead, they leased space for their shop from building owners. Business conditions and lease expenses prompted their moves; they relocated as their need for additional sales and production space grew. Only the shop at 23 West Second Street was in downtown Dayton, and it failed because it was too close to three other bicycle shops. Fewer competing cycle shops were located in west Dayton. What would a Wright bicycle cost today? Wright-made bicycles, sold between 1896 and 1900, cost from $30 to $65, depending on the model purchased (the equivalent of roughly $650-$1,400 in 2002). Wright models included the Van Cleve, named for one of their ancestral families; the St. Clair, named for Revolutionary general, first governor of the Northwest Territory and founder of Dayton, Arthur St. Clair (1734-1818); and the Wright Special. Five known Wright bicycles exist today; all are owned by museums and are priceless. Why are the house where the Wrights grew up and their last cycle shop in Michigan? The fifth and final Wright Cycle Shop (1127 West Third Street) and the Wrights’ home at 7 Hawthorne Street no longer stand at their original Dayton locations. Instead, they are in Dearborn, Michigan, as part of Greenfield Village, a museum that contains an idealized community of buildings brought to Michigan from across the United States started by industrialist Henry Ford during the 1920s. The first efforts to honor the Wrights in Dayton concerned the construction of stone memorials, not the preservation of buildings connected with their lives (which was uncommon anywhere in the United States before the 1930s). Before 1948, the Science Museum in London displayed the 1903 Wright airplane. With his unresolved feud with the Smithsonian Institution over the recognition given Samuel Langley’s Aerodrome as the first airplane capable of sustained, powered, controlled flight, Orville Wright indicated to Ford and a group of pioneer airplane pilots known as the Early Birds that it was unlikely that the 1903 airplane would return to the United States in the near future. However, Orville was interested in preserving the Wright home and the fifth cycle shop. With preservation of the buildings at their original sites in Dayton uncertain, he worked with Edsel and Henry Ford to purchase the cycle shop building from its owner, Charles Webbert, for $13,000. The Fords purchased the house at 7 Hawthorne Street for $4,100. They then moved the buildings to Dearborn, Michigan, where their craftsmen painstakingly rebuilt them. Twenty tons of dirt from Dayton accompanied the two buildings to Michigan; Ford wanted them to still stand on Ohio soil. Where are the Wrights buried? Milton, Susan, Wilbur and Orville Wright and Katharine Wright Haskell are buried in Woodland Cemetery in Dayton. The family plot is at the base of three flagpoles erected in their honor. Did Wilbur or Orville ever marry or have children? Neither Orville nor Wilbur married or fathered children. However, their elder brothers Reuchlin and Lorin married and had children, and their sister Katharine married later in life. While Reuchlin’s family lived in Kansas, Lorin’s four children – who lived in Dayton – were favorites of Wilbur and Orville. |

Last updated: April 10, 2015