Guidelines for Restoring Cultural Landscapes

Spatial Organization + Land Patterns

Identify, Retain, and Preserve Historic Materials and Features from the Restoration Period

![]()

Identifying, retaining and preserving the existing spatial organization and land patterns of the landscape from the restoration period. Prior to beginning project work, documenting all features which define those relationships. This includes the size, configuration, proportion and relationship of component landscapes; the relationship of features to component landscapes; and the component landscapes themselves such as a terrace garden, a farmyard, or forest-to-field patterns.

![]()

Undertaking project work without understanding the effect on the existing spatial organization and land patterns. For example, constructing a structure that creates new spatial divisions or not researching an agricultural property’s development history.

Protect and Maintain Features and Materials from the Restoration Period

![]()

Protecting and maintaining features that define spatial organization and land patterns from the restoration period by non-destructive methods in daily, seasonal and cyclical tasks. For example, maintaining topography, vegetation, and structures which comprise the overall pattern of the cultural landscape.

![]()

Allowing spatial organization and land patterns from the restoration period to be altered, for example, through incompatible development or neglect.

Utilizing maintenance methods which destroy or obscure the landscape’s spatial organization and land patterns from the restoration period. For example, allowing field succession to obscure a historic farm and field pattern.

Repair Features and Materials from the Restoration Period

![]()

Failing to undertake necessary actions resulting in the loss of spatial organization and land patterns. For example, allowing a post and rail fence to deteriorate

![]()

Replacing a feature from the restoration period that defines spatial organization and land patterns when repair is possible. For example, replacing a hedge when the original hedge could have been pruned to generate new growth.

Replace Extensively Deteriorated Features from the Restoration Period

![]()

Replacing in-kind an entire feature from the restoration period that defines spatial organization and land patterns that is too deteriorated to rejuvenate. For example, replanting in-kind an historic orchard.

![]()

Removing a feature from the restoration period that is beyond repair and not replacing it; or replacing it with a new feature that does not respect the spatial organization and land patterns of the restoration period. For example, removing a hedgerow and not replanting it.

Remove Existing Features from Other Historic Periods

![]()

Removing or altering features from other historic periods that intrude on the historic spatial organization and land patterns. For example, removing a skinned baseball field from a historic meadow.

Documenting features dating from other periods prior to their removal or alteration. If possible, selected examples of these features and materials should be stored to facilitate future research.

![]()

Failing to remove features from another period, thus confusing the depiction of the cultural landscape’s spatial organization and land patterns during the restoration period. For example, failing to remove a chain link fence where no fence historically existed.

Failing to document features from other historic periods that are removed or altered so that a valuable portion of the historic record is lost.

Re-Create Missing Features from the Restoration Period

![]()

Recreating a missing feature important to the spatial organization and land patterns during the restoration period based on historical, pictorial and physical documentation.

![]()

Constructing a feature that contributes to the overall spatial organization and land patterns which was thought to have existed during the restoration period, but for which there is insufficient documentation; or, constructing a feature that was part of the original design but was never executed.

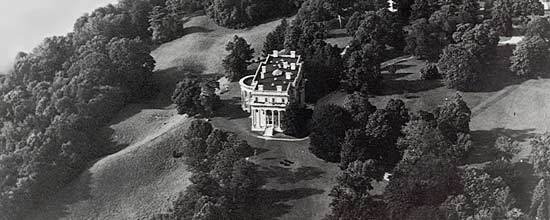

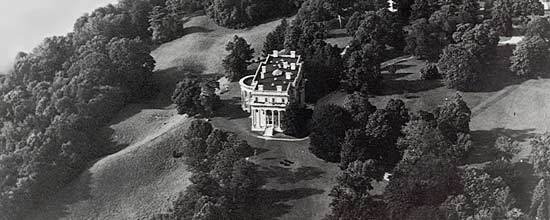

The spatial organization and land patterns of the 211-acre landscape at the Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Site in Hyde Park, New York, woodland edges are being restored. This historic aerial photograph from the 1930s, [top] provides excellent documentation of the spatial organization during the landscape’s period of significance from 1830-1939. Project work re-establishing lost meadow areas that were overtaken from 1939 to the present are illustrated on the treatment plan. [below] (Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Site and LANDSCAPES)

Until recently, spatial relationships at Stan Hywet Hall had changed due to a lack of maintenance [top]. The view, which has recently been reinstated, creates a strong visual link between the house and the larger landscape, originally designed by Warren H. Manning [bottom]. (Stan Hywet Hall Foundation)

Based on historic plans, photographs and tree corings, the ca. 1930 lawn space at the Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site in Brookline, Massachusetts, has been re-created through the removal of invasive woody species. (NPS)