Guidelines for Preserving Cultural Landscapes

The Approach

Introduction

In Preservation, the options for replacement are limited. The expressed goal of the Standards for Preservation and Guidelines for Preserving Cultural Landscapes is retention of the landscape’s existing form, features and materials, provided that such actions will not result in a degraded landscape condition or threaten historic resources. Preservation treatments may be as simple as basic maintenance of existing materials and features, such as the upkeep of a pedestrian path with a topcoat of crushed shells, or may be more involved; for example, preparing a cultural landscape report, undertaking laboratory testing (e.g. pollen analysis to identify past uses of the property or hiring conservators to perform sensitive work (e.g. repointing a serpentine garden wall). In all cases, protection, maintenance, and repair are emphasized, while replacement is minimized.

Identify, Retain, and Preserve Historic Materials and Features

The guidance for the treatment Preservation begins with recommendations to identify the form and detailing of those features and materials that are important to the landscape’s historic character and which must be retained in order to preserve that character. Therefore, guidance on identifying, retaining, and preserving character-defining features is always g iven first. The character of a cultural landscape is defined by its spatial organization and land patterns; features such as topography, vegetation, and circulation; and materials, such as an embedded aggregate pavement.

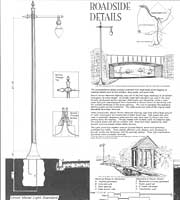

Historic road details were inventoried and documented along the George Washington Memorial Parkway where two light standards were used: an ornate metal post for more formally landscaped areas between Washington D.C. and Alexandria, Virginia, while a rustic cedar pole was employed from Alexandria to Mount Vernon to harmonize with its setting. (HABS, 1994)

Stabilize and Protect Deteriorated Historic Features and

Materials as a Preliminary Measure

Features within a cultural landscape may need to be stabilized or protected through preliminary measures until additional work can be undertaken. Stabilization may include structural reinforcement of a rustic pergola, cabling of a tree, weatherization of a wooden garden bench, or correcting unsafe conditions. This work should always be carried out in such a manner that it detracts as little as possible from the cultural landscape’s appearance. Although it may not be necessary in every preservation project, stabilization is nonetheless an integral part of the treatment Preservation; it is equally applicable, if circumstances warrant, for the other treatments. Protection generally involves the least degree of intervention and is preparatory to other work. Such actions would include the installation of temporary fencing around significant plant materials or the electrical grounding of a tree.

To preserve a century-old oak, a stabilization rod [see left side of photo] was applied to a limb that overhangs a pedestrian walk at the Alamo, San Antonio, Texas. (author, 1993)

Maintain Historic Features and Materials

After identifying, protecting and stabilizing those features and materials that are important and must be retained, maintaining them becomes important. For example, maintenance includes treatments such as removing rust from an iron light standard, repointing a stone footbridge, re-application of protective coatings on a wooden patio deck; pruning to maintain the form of a hedge; monitoring the age, health and vigor of plant materials; or the cyclical cleaning of drainage inlets. As a foundation for these decisions, an overall evaluation of a cultural landscape’s existing conditions should always begin at this level.

[top and right] At the Irwin Miller House, Columbus, Indiana, the integrity of the original design by landscape architect Dan Kiley has been preserved by respecting the original design intent and maintaining the height of the hedges at 8’-6”. (author, 1995)

Repair (Stabilize, Consolidate and Conserve) Historic Features and Materials

When the existing conditions of character-defining features and materials requires additional work, their repair is recommended. Preservation strives to retain the maximum amount of existing materials and features while utilizing as little new material as possible. Consequently, guidance for repairing a historic feature, such as vegetation, begins with the least degree of intervention possible, such as pruning a tree to lighten its canopy [see opposite]; or, in some cases, pruning back a shrub to the ground to encourage vigorous and healthy new growth. Similarly, within the treatment Preservation, portions of a historical structural system could be reinforced using contemporary materials. A capstone on a retaining wall, or a board in a wooden walkway, may be repaired with contemporary replacement parts. In all cases, work should be non-destructive, physically and visually compatible, and documented for future research.

This character-defining avenue of oaks in Forsyth Park, Savannah, Georgia, have been pruned to lighten their canopy, thus providing protection from severe storms. (author, 1996)

Limited Replacement In Kind of Extensively Deteriorated

Portions of Historic Features

If repair by retention of an entire historic feature and/or its historic materials proves impossible, the next level of intervention involves the limited replacement in kind of portions of historic features when there are surviving prototypes. For example, this might involve replacing dead shrubs in a bank planting with same-genus, species/variety shrubs; or, replacing missing fence members to match surviving components. The replacement material should match the historic both physically and visually. In all cases, substitute materials are not appropriate in the treatment Preservation. However, exceptions would include hidden structural reinforcement, new mechanical system components (ex. adding irrigation), and the lack of availability or hazardous nature of original materials. For example, when matching plant materials are no longer commercially available, may not be hardy to a region, or, are highly disease prone, substitute plants may be recommended. In these cases, it is important that all new material be non-destructive, identified, and properly documented for future research. Generally, in Preservation, substitute materials should be avoided, unless in-kind replacement is not possible.

Castings were made to replace a limited number of lost finials along the perimeter fence of Lafayette Square, St. Louis, Missouri. (author, 1994)

Special Considerations (Accessibility, Health and Safety, Environmental, and Energy Efficiency)

These sections of the Preservation guidance address work done to meet accessibility requirements; health and safety code; environmental requirements; or limited retrofitting measures to improve energy efficiency. Although this work is quite often an important aspect of preservation projects, it is usually not part of the overall process of protecting, stabilizing, conserving, or repairing character-defining features; rather, such work is assessed for its potential negative impact on the landscape’s character. For this reason, particular care must be taken not to obscure, damage, or destroy character-defining materials or features in the process of undertaking work to meet code and energy requirements.

This easily-reversible accessibility solution has been installed at Mission San Jose, San Antonio, Texas. (author, 1994)