Photo credit Ben Henalt.

Photo credit Ben Henalt.

Zombie Effect

The notion of the zombie –having an infectious disease seize total control of your mind and transform you into a mindless slave –sometimes called the 'walking dead' –is the stuff of horror films. The zombie is inherently terrifying because it is an assault on our most cherished human quality – our free will - to act independently and decide for ourselves.

Fittingly, when one leaves the sun-drenched Chihuahuan desert and ventures into the caverns, the zombie effect becomes something more than fiction –it becomes real, though not for humans, but for the cavern's blind, leaping crickets.

Deep in the caverns, food scarcity looms large. Cave crickets will consume anything available –including each other. Most crickets are famously cacophonous, but you will not hear them in the caverns; they remain silent, so as not to alert any potential prey, or other crickets, of their location.

But the cricket's greatest threat does not walk on land –it lurks in the water. Parasites, in the form of worm larvae, float in the cave's pools, waiting for a cricket to take a sip of water. And once inside their cricket host, the young worms do not simply exploit the cricket's bodies –they take control of their minds.

The goal of parasitism is to benefit from the host, but still continue to keep it alive. The baby horsehair worms at the Carlsbad Cavern's enter the cricket's body cavity, wherein they consume its fat stores but spare the vital organs. Here, they begin to grow.

Four hours north of the Carlsbad Caverns is a researcher, Dr. Ben Hanelt, who has devoted his academic career to investigating this fascinating biological niche. Dr. Hanelt says that horsehair worms cannot live out of water, which provides a challenge because crickets cannot swim, and except when thirsty, avoid water at all costs.

How then, can the worms ensure that their terrestrial cricket hosts will deposit them back into the safe confines of their natural water environment? "The worm literally extends into the head of the cricket," says Dr. Hanelt. "And usually, the worm makes intimate contact with the brain."

One study showed that the worm produces specific neurotransmitters – chemicals that influence the mind –and then excretes them into the cricket's brain.

Similar to one being compelled to enter a house that is engulfed in flames, a cricket will be driven to do something strange and dangerous –seek a body of water. Once there, the worm directs the cricket to jump in the water.

"This is really a death sentence for the cricket," says Dr. Hanelt. "The crickets can't swim."

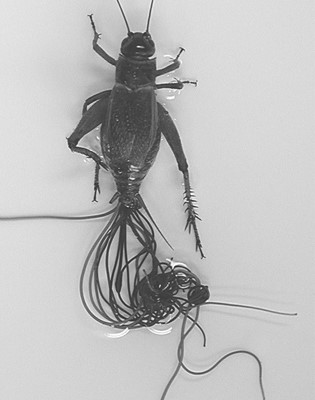

The story grows more lurid: Once the cricket has jumped into the water, the worm is prepared to emerge. It bores through the cricket's body and enters the cave pools, fully grown, and eager to reproduce.

None of this is fanciful – this specific effect has been observed in Dr. Hanelt's laboratory. When infected crickets were placed in a Y-maze that led either to a pool of water versus no water, the infected crickets chose the path that led to water, and once there, promptly jumped in. Conversely, none of the healthy crickets chose to voluntarily drown.

It is common to find lifeless crickets in cavern pools. We can gaze at them and be relieved that we are not susceptible to the selfish whims of a ruthless parasite.

Or are we?

"There are absolutely parasites that can manipulate human behavior," says Dr. Hanelt. Over a century ago, in 1896, Scientific American published an article entitled "Is insanity due to a microbe?," which proposed a link between a small amoeba-like protozoan, toxoplasma, and schizophrenia.

Today, the relationship between this single-celled creature and humans is growing ever more convincing. Toxoplasma changes the brains of warm-blooded creatures, traditionally being passed between rodents and cats. The parasite desires to spread, and its primary behavioral manipulation is to increase its host's propensity for risk-seeking behavior. For instance, infected mice and rats begin to act in strange ways that leave them susceptible to predation; rats lose their innate aversion of the creatures that seek to kill them – cats – and even seek out the smell of cat urine. In this way, cat's become infected too, and the parasite continues its spread.

Unfortunately for humans, toxoplasma is transmitted from infected animals to people via contaminated food. Raw or undercooked meat, specifically beef, is a common source of transmission, although there are others, such as exposure to cat litter. Most of us, however, are able to resist these microbes and keep their parasitism at bay.

But it is when we are weak or sick that the parasite can cross into our brains. An estimated two percent of North American's have enfeebled immune systems, such as pregnant women, senior citizens, and cancer patients.

In its most severe form toxoplasma directly impacts the brain, destroying neural tissue and forming lesions. Similar to toxoplasmosis in rats, humans show an irrefutable increase in risk-seeking behavior. For instance, the effects of this brain damage were associated with car accidents in Europe – researchers showed that infected individuals were nearly three times as likely to be involved in traffic accidents .

Much is still being learned about this curious parasite, but other behavioral manipulations have been observed. For instance, chronically infected men become easily jealous, emotionally unstable, suspicious, and quick to temper. And as noted early, for over 100 years there has been a strong suspicion that toxoplasmosis may precipitate an extreme and involuntary change in one's perception and understanding of the world –schizophrenia.

Like all parasites, toxoplasma will strive to find news hosts, and it is clear that humans are not immune.

Indeed, there are few things as unsettling as brain manipulation. But at the very least, we are not like cave crickets in the dark, unwitting swallowing parasites that can infect our minds and control our actions.

Or are we?