|

Native American tribes living on the Atlantic coast, being the first peoples to come in contact with European explorers, were hit hardest by the introduction of foreign diseases and wars with the colonists. Many eastern North Carolina tribes were completely destroyed and survivors, if there were any, integrated into other tribes or nearby white and black communities. This rapid loss of life and culture and the limited number of records mean that the lives of many of these people remain cloaked in mystery.

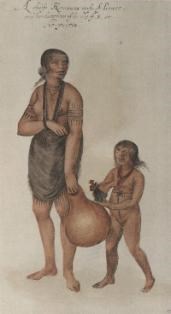

John White, digital image courtesy of the British Museum The Meeting of Three Cultures Carteret and Craven Counties in coastal North Carolina represent a meeting of the three cultures of the North Carolina coast: the Cashie Tradition of tribes belonging to the Iroquois language family; the Colington Tradition of tribes belonging to the Algonquain language family; and the Oak Island / White Oak Tradition of tribes belonging to the Sioux or, perhaps in some locations, Algonquian language families. For this reason and because no part of their language was recorded, experts have not been able to determine with certainty the culture and language family of the Coree, who were living near Cape Lookout at the time of European contact. The Coree were closely tied with both the Machapunga, an Algonquain-speaking tribe located near Lake Mattamuskeet, and the Tuscarora, a large Iroquoian tribe located to the northwest. The Coree fought alongside both tribes: in the Tuscarora War and in small raids with the Machapunga. The connection between the Coree and the Tuscarora is so close that some have speculated that the Coree might have been part of the Tuscarora before moving eastward and becoming a separate tribe (or becoming a less closely tied sub-tribe of the Tuscarora Confederacy). On the other hand, explorer John Lawson notes that the Tuscarora tribe was so large that someone in every town of every nearby tribe knew their language. The Algonquain and Iraquoian tribes of coastal North Carolina regularly traded with each other as well, which could easily explain the Coree tribe's ties to either of these neighbors. Another example of this uncertainty comes from the Piggot Ossuary, a Colington (Algonquain) site located north of Harkers Island. This area likely belonged to the Coree (Coranine) in 1709 when Lawson wrote his manuscript placing the tribe at Cape Lookout, but the site predates Lawson (1420-1640). Archaeologists excavating the Piggot site in the 1970s suggested that it may have belonged to the Neusiok tribe, although others have suggested that the Neusiok were Iroquoian not Algonquian. And, in 1709, Lawson places the Neusoik further north. Did the Coree move into the area around Cape Lookout and Core Banks after an Algonquain tribe left? Or, does this site support the hypothesis that the Coree were Algonquain speakers? We may never know. Why is the language family and cultural tradition of the Coree so important? It would give us a much better view into the daily lives of these people based on the cultural practices of similar tribes.

John White, digital image courtesy of the British Museum Colington Tradition: Colington tribes were organized as chiefdoms: a chief in the capital village ruled the people in several common and seasonal villages. While crops were maturing in the capital village or on farmsteads, some people moved to seasonal villages to hunt or fish. Although the chief held great political power and priests had marked religious authority, Colington tribes were generally ruled by consensus. The chief generally took the advice of the tribal council. This democratic political and religious system was distinctly different from the Mississippian chiefdoms found in the North Carolina Piedmont. As with other coastal tribes, the Colington Algonquians used ossuaries, special buildings designed for storing the bones of the dead. Unlike other coastal tribes, these were community burials. Priests maintained mortuary temples, where the dead were kept until the mass burial ceremony. It seems, although it is not clear, that ossuaries were built near the village on the northern edge. Visit UNC Chapel Hill's Colington Phase (800 to 1600 AD) for more information on this culture.

John White, digital image courtesy of the British Museum Cashie Tradition: The Cashie (ca-SHY) culture gets its name from the style of pottery made in North Carolina by Iroquois tribes between AD 800 and 1750. These tribes occupied the Inner Coastal Plains region, building their villages near the rivers’ uplands where the most fertile soil could be found. Although their daily lives were similar to the other coastal tribes, the Cashie had a different political system. Each village maintained political independence. The most famous example is the autonomy of the three tribes in the Tuscarora Confederacy; although they were allied with each other, each tribe in the confederacy was independent. The Cashie built ossuaries for their dead, as did other coastal tribes. However, these were typically family burials of less than 6 people. Also unlike their Algonquain neighbors, the Cashie included grave offerings such as bone tools and shell beads. Visit UNC Chapel Hill's Cashie Phase (800 to 1650 AD) for more information on this culture.

John White, digital image courtesy of the British Museum White Oak (Oak Island) Tradition: Of the three coastal cultures, White Oak / Oak Island is the least widespread and the least studied. Because their pottery resembles styles found south of this region more so than those of the mid- or upper North Carolina coast, archaeologists believe that this culture held closer ties to tribes in present day South Carolina. However, these Siouian, and possibly Algonquian, tribes buried their dead in ossuaries, like their neighbors to the north. Visit UNC Chapel Hill's White Oak Phase (800 to 1500 AD) for more information on this culture. |

Last updated: April 14, 2015