NPS A Black Woman and $5Charlotte Scott began the journey that led to this monument. After President Abraham Lincoln's murder, Scott gave $5 towards what she hoped would be a memorial. Recently emancipated from enslavement, this was her first money earned as a free Black woman. From here, $20,000 was given by Black Americans, many of who shared Ms. Scott's status as recently freed persons.The St. Louis-based Western Sanitary Commission held the money. These white abolitionists searched for a design. There is no evidence anyone outside this group had a say in the design. Black folks paid for it; white folks chose it. Harriet Hosmer proposed a multi-level memorial showing Lincoln alongside several Black Americans. This ambitious design was compelling, but too expensive. A simpler, more affordable design was needed. William Greenleaf Eliot was one of the monument committee. Years before he saw small sculpture done by Thomas Ball, a white American sculptor in Munich. When Ball heard of Lincoln's death in 1865, he wrote, "I could not free my mind from the horror of it." At the same time Charlotte Scott donated her $5, Thomas Ball began sculpting a memorial. They were unaware of each other. Later, when Eliot saw the completed memorial of Lincoln and an enslaved man and asked Ball if they could use it. "Of course I accepted their offer, for you must remember that every cent of this money was contributed by the freed men and women," Ball reflected.

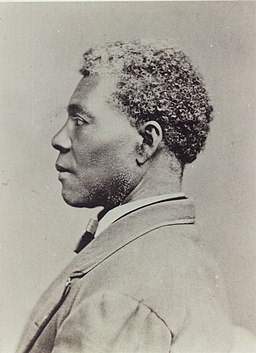

NPS A Black Man as the ModelSome changes occurred. The enslaved individual's face was now modeled off Archer Alexander. Alexander is often called the last person taken under the Fugitive Slave Act. A hat came off, and a pile of books became a pedestal. In 1875, the statue traveled to Washington to be placed in Lincoln Park.The statue, called “The Emancipation Group” or “Freedman’s Memorial,” was dedicated April 14, 1876. On the 11th anniversary of Lincoln’s death, nearly every African American organization in the city joined in a large parade. As it snaked its way through the city, a crowd buzzed in anticipation. Before the crowd stood the statue covered in flags and bunting. A stage next to the monument eagerly awaited them. President Ulysses Grant arrived. The formerly enslaved Blanche Kelso Bruce was with him. Bruce was now a Mississippi Senator. As the parade got closer, they saw “twenty-seven mounted police, followed by three companies of black militia troops, headed by the Philharmonic Band of Georgetown. Numerous other cornet bands, marching drum corps, youth clubs in colorful uniforms, and fraternal orders from both Washington and Baltimore filled in the long line with pride and pomp. The Knights of St. Augustine carried a large banner with a painting of the martyred Lincoln.” With them were Master of Ceremonies, John Mercer Langston, and featured orator Frederick Douglass. The Marine Band struck up “Hail, Columbia” as nearly 25,000 spectators angled for a view. Readings and music occurred. The head of the Western Sanitary Commission gave the history of the monument. After this address, John Mercer Langston invited President Grant to reveal the monument. He grabbed the cord in his hands, and “as Grant stood still for a long moment, the entire crowd hushed in rapt silence.” As the stars and stripes slid off the bronze memorial, thousands roared in applause and shouts. Cannons nearby thundered into the heavens. Lincoln's face again looked upon the nation's capital. The Marine Band erupted in "Hail to the Chief," followed by letters and poetry.

Public domain Frederick Douglass Addressed Attendees of the Memorial DedicationThen stepped forward Douglass. Above him was a standing Lincoln, left hand stretched over the head of Archer Alexander. Lincoln’s right hand gripped the Emancipation Proclamation. The Proclamation was on a plinth – a heavy support structure common for works of art. On it are patriotic symbols: George Washington, a shield with stars and stripes, and a bundle of reeds strapped together. Behind is a small whipping post, draped in cloth. On the back of the post was a pillory and ring where the chains, now broken, once secured. A vine creeps through these rings, showing chains as a thing of the past.

NPS Frederick Douglass' Further Reflections on the Emancipation StatueAs sunset fell upon this new statue for the first time, the immense crowd went about their days. The statue remained. Future generations still ask: Just what exactly shown here? Even Douglass was not sure. In his speech, he both praised and criticized Lincoln. Days later, Douglass continued thinking about this new statue. How do you truly honor and remember all who had a share in emancipation?Five days later, in an April 19, 1876 letter to the National Republican, Douglass revealed more of his thoughts: “Admirable as is the monument by Mr. Ball in Lincoln park, it does not, as it seems to me, tell the whole truth, and perhaps no one monument could be made to tell the whole truth of any subject which it might be designed to illustrate. The mere act of breaking the Negro's chains was the act of Abraham Lincoln, and is beautifully expressed in this monument. But the act by which the negro was made a citizen of the United States and invested with the elective franchise was pre-eminently the act of President U.S. Grant, and this is nowhere seen in the Lincoln monument. The negro here, though rising, is still on his knees and nude. What I want to see before I die is a monument representing the negro, not couchant on his knees like a four-footed animal, but erect on his feet like a man. There is room in Lincoln park for another monument, and I throw out this suggestion to the end that it may be taken up and acted upon.” Discomfort about the statue can serve as a reminder of the exhilarating, turbulent, and often violent period of Reconstruction. It reflects hopes, dreams, and – for many – coming failure. So many questions impacting the future were being forged in those moments. While America transforms around it, the Freedman's Memorial and Bethune Memorial are frozen in time, a silent witnesses to every generation that has battled for justice from Charlotte Scott, with her $5 and a vision, to the present. |

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov

A

.gov website belongs to an official government

organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A

lock (

) or https:// means you've safely connected to

the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official,

secure websites.