Key Clauses of the 14th Amendment

July 9, 1868

In 1865, the United States approved the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution. They added the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868 and the Fifteenth in 1870. Together, these three amendments are known as the Reconstruction Amendments. On paper, they greatly expanded the civil rights enjoyed by those formerly enslaved. Such rights included the right to be free and the right to vote. The Fourteenth Amendment, passed on July 9, 1868, contains many of the key elements of our modern civil rights. The majority of these elements are in Section 1 of the amendment, listed out below.

Citizenship Clause

All people born or naturalized in the United States are citizens of the United States. These people have every right belonging to citizens. (Naturalization is a way in which people born elsewhere can become citizens of a country.)

Privileges or Immunities Clause

States cannot make laws that take away the fundamental rights enjoyed by all people.

Due Process Clause

States cannot take away a person’s fundamental rights without first following the necessary and proper legal steps.

Equal Protection Clause

States must treat all people within their legal systems the same way that they treat other individuals in the same or similar situation.

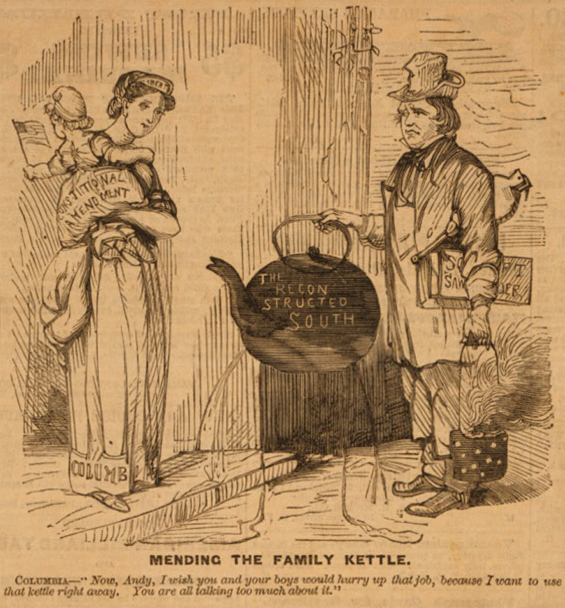

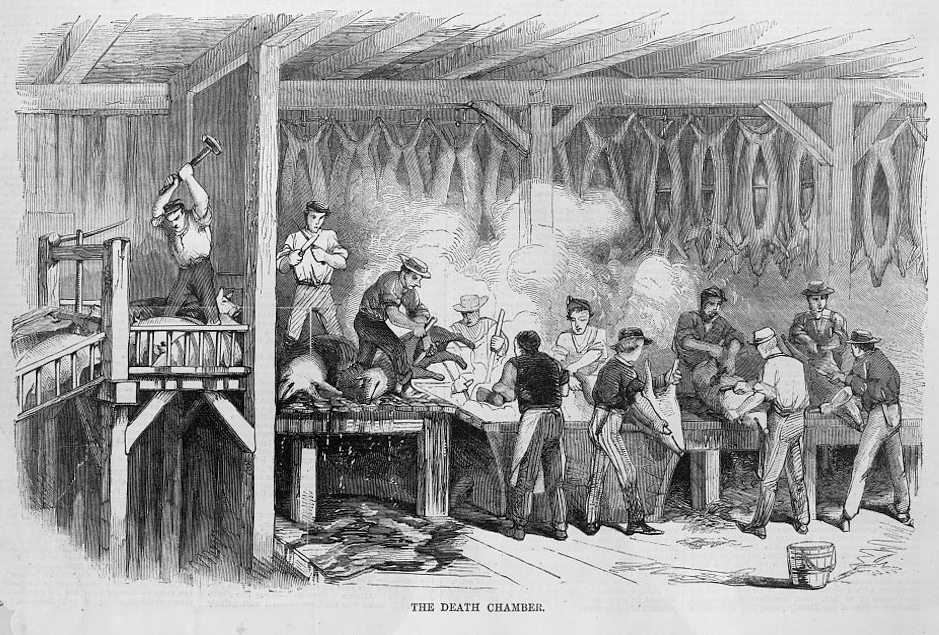

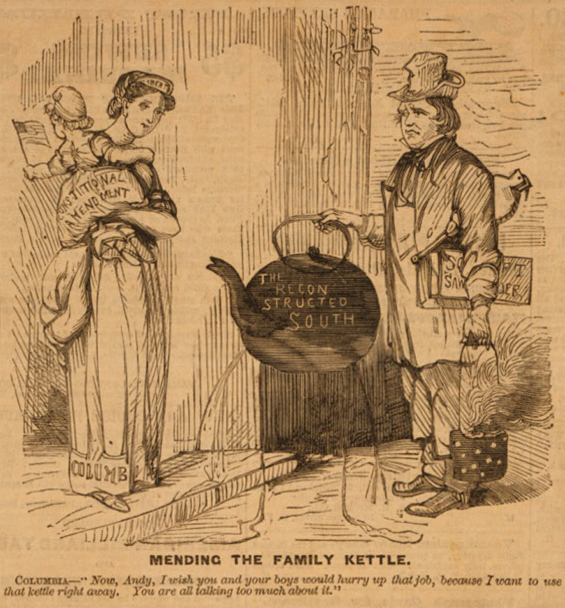

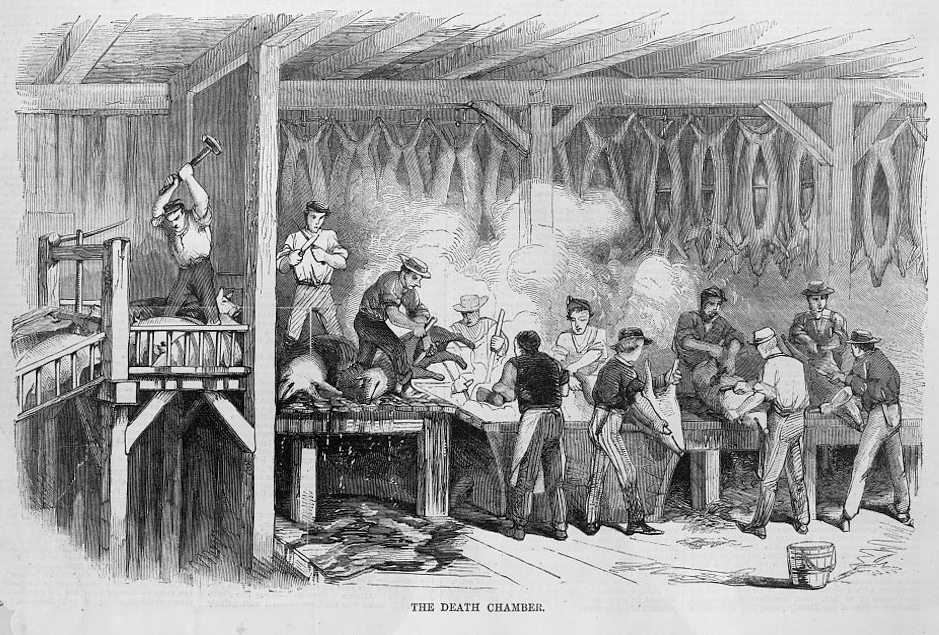

The Slaughterhouse Cases

April 14, 1873

Louisiana passed a law making the Crescent City Live Stock Landing and Slaughter House Company a monopoly in New Orleans’ slaughterhouse industry. A handful of workers sued the state.

The Issue.

1) Can a state government create a monopoly?

2) Did the creation of these monopolies violate the Thirteenth or Fourteenth Amendments?

The Ruling.

1) Yes, a state government can create monopolies. A state can do so using what is called “police power.” Police power allows states to have sole authority over laws regarding local health, safety, and business.

2a) No, state creation of monopolies did not violate the Thirteenth Amendment. While ‘servitude’ can take many forms, the Thirteenth Amendment only outlawed race-based slavery.

2b) No, state creation of monopolies did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment. There is a legal difference between citizens of the United States and citizens of a particular state like Louisiana. The Fourteenth Amendment applied only to citizens of the United States. Congress lacked the authority to address the claimed violations. The Fourteenth Amendment was not applicable to this case.

Notable Dissent.

Four members of the Supreme Court disagreed with the majority’s ruling. They argued that several parts of Louisiana’s law did not fall under police power. They also maintained that the Thirteenth Amendment outlawed any and all forms of involuntary servitude, including monopolies. Monopolies create a form of slavery by limiting workers’ freedom to pick who they work for. Finally, the dissenters believed that the Fourteenth Amendment protected against violations by states as well as federal violations.

Why Does It Matter?

The majority ruling took on a limited view of the Reconstruction Amendments and a broad view of police power. They ruled that the Fourteenth Amendment does not apply to the actions of state governments. The majority also said that the state has broad authority under its right to exercise police power.

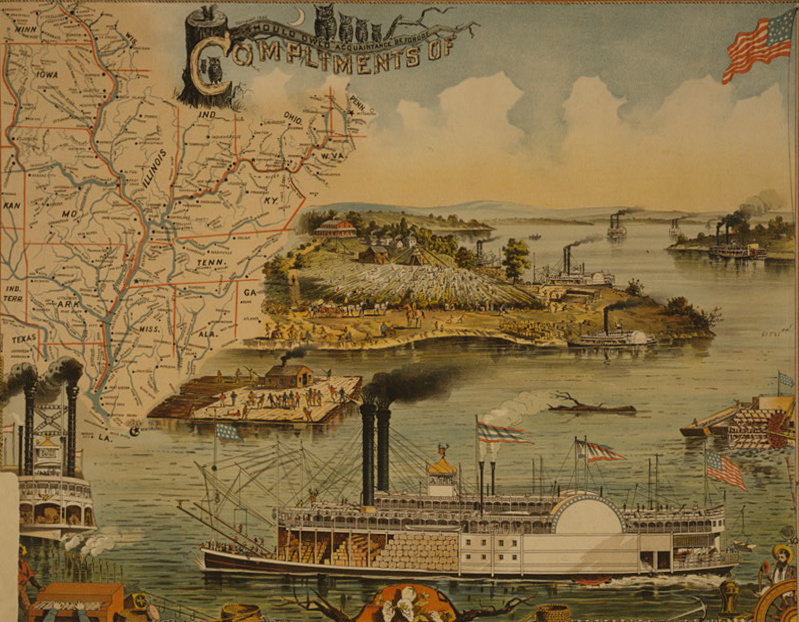

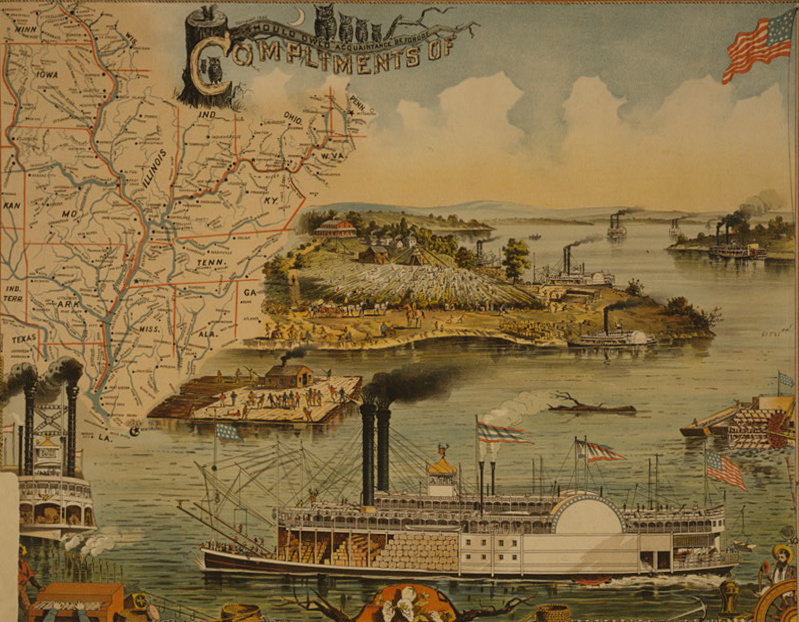

Hall v. DeCuir

October 1, 1877

In 1869, Louisiana passed a law prohibiting racial segregation on common carriers. Common carriers are individuals or corporations that transport goods and/or people for any member of the public who can pay the fee. In 1872, Josephine DeCuir bought a ticket for the steamboat Governor Allen. She tried to enter a whites only cabin. The captain refused to let her in as she was black. DeCuir sued the captain and won in the lower courts. The captain’s estate challenged the ruling.

The Issue.

Did a state law banning racial segregation on common carriers violate the Constitution?

The Ruling.

Yes. The Commerce Clause of the Constitution gave Congress the exclusive right to control interstate commerce. Common carriers like steamboats did business in multiple states and were regulated by national laws on interstate commerce. The state of Louisiana could not pass laws affecting interstate commerce without violating the Commerce Clause.

Notable Dissent.

None. This ruling was unanimous.

Why Does It Matter?

This ruling limited a state’s power over public transportation that passes through its borders.

Ex Parte Virginia

October 1879

In 1878, Pittsylvania county judge J.D. Coles was in charge of selecting the pool of possible jurors for the year. Not a single man selected was a man of color. Coles was arrested for violating the Civil Rights Act of 1875. This federal law prohibited the exclusion of any citizen from jury duty because of his race. Coles challenged his arrest in the courts.

The Issue.

Did Congress have the authority to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1875?

The Ruling.

Yes. The Fourteenth Amendment added several new rights to the Constitution. One of these rights was equal protection before the law, regardless of one’s race. This amendment was also intended to limit state power and expand federal power. The Civil Rights Act of 1875 fell within the congressional authority granted by the Fourteenth Amendment.

Notable Dissent.

Justices Stephen J. Field and Nathan Clifford disagreed with the majority. They argued that jury duty was not a right of citizens of the United States. If it was, then women and children who are citizens should also be allowed to serve on juries. Instead, jury duty is a right of citizens of the states. Therefore, Congress lacked the authority to pass a law controlling jury duty.

Why Does It Matter?

The majority ruling upheld the Congress’s power to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1875.

Strauder v. West Virginia

March 1, 1880

Taylor Strauder, a black man, went on trial for a crime in 1874. There were no black men on his jury. West Virginia law stated that only white men could serve on the jury in that state. Strauder sued the state for violating his constitutional right to equal protection before the law.

The Issue.

Did laws excluding black men from the jury pool violate the Fourteenth Amendment?

The Ruling.

Yes. One element of the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause was the right to be tried by a jury of one’s peers. States could limit jury pools in some ways but race could not be the limiting factor. Otherwise, such discrimination would make the white and black races unequal before the law.

Notable Dissent.

Justices Stephen Field and Nathan Clifford renewed their dissents from the case of Ex Parte Virginia (1879). Jury duty is not a right of citizens of the United States and cannot be protected by the federal government. Only states have the power to control the jury pool within their borders.

Why Does It Matter?

The majority ruling reaffirmed the right of all races to be treated as equal by the law. The majority also declared jury duty as an essential right of U.S. citizens.

The Civil Rights Cases

October 15, 1883

In five separate situations, a person of color was denied access to businesses. The businesses in question were two inns, two public theaters, and a train car. The individuals each sued for racial discrimination in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. The Civil Rights Act of 1875 also outlawed this type of discrimination. The Supreme Court grouped these cases together for its ruling.

The Issue.

Did the business owners’ denials of access because of one’s race violate the Fourteenth Amendment?

The Ruling.

No. The Fourteenth Amendment protected against racial discrimination from the government. It did not protect against the private acts of individuals. For this reason, the Civil Rights Act of 1875 was actually unconstitutional. Congress could not control the actions of private individuals or businesses.

Notable Dissent.

Justice John Harlan was the only one who disagreed with the majority. He believed that Congress did have the right to control the acts of individuals if their work was public in nature. If a business was said to be open to the public, then they had to accept all members of that public as customers. Or, at the very least, public businesses could not reject customers because of their race.

Why Does It Matter?

The majority ruling effectively reversed the finding in Ex Parte Virginia. The Civil Rights Act of 1875 became illegal.

Yick Wo v. Hopkins

May 10, 1886

The city of San Francisco passed an ordinance in 1880 requiring new permits for laundry owners. Of the city’s 320 laundries, about 240 were run by Chinese owners and 80 by white American owners. The laundry owners applied for the new permit. Almost all the white American launderers met the conditions and received permits. At least 151 Chinese launderers met the conditions but did not receive permits. Two of those Chinese launderers, Yick Wo and Wo Lee, sued the city sheriff for racial discrimination. Sheriff Hopkins denied the accusations. He claimed that he was simply exercising the city’s police power.

The Issue.

1) Were non-citizens protected by the U.S. Constitution? 2) Did Hopkins’ actions fall within the limits of police power? 3) Did Hopkins’ actions violate the Fourteenth Amendment?

The Ruling.

1) Yes, the Constitution guaranteed some rights to non-citizens. As the Fourteenth Amendment said, “Nor shall any State deprive any person” of their equal protection under the law.

2) No, Hopkins’ actions were not police power. His enforcement of the city ordinance was not based on a set of impartial rules. Both the Americans and the Chinese launderers met the conditions to receive a permit. It was only due to Hopkins’ own arbitrary whims that the Chinese launderers were rejected.

3) Yes, Hopkins’ actions treated Americans and Chinese as separate and unequal groups before the law. This was a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause.

Notable Dissent.

None. This ruling was unanimous.

Why Does It Matter?

The majority ruling expanded the protections of the Constitution to include non-citizens. At a time when the Chinese were excluded from citizenship, the Supreme Court asserted that even foreign nationals had certain rights that no government could violate. The ruling also limited what was considered police power and affirmed the illegality of racial discrimination by the government.

Louisville, New Orleans & Texas Railway Company v. Mississippi

March 3, 1890

In 1882, the state of Mississippi passed a law requiring railroad trains to have separate cars for white and colored passengers. The Louisville, New Orleans and Texas Railway Company did not have segregated passenger cars while passing through the state. Mississippi sued the company, and the lower courts ruled in the state’s favor. The railroad company challenged the rulings.

The Issue.

Was a state law requiring racial segregation on railroad trains constitutional?

The Ruling.

Yes. Although state laws affecting common carriers such as railroad trains normally violated the Commerce Clause, it was not so in this case. The Mississippi law only affected railroad transportation within the state’s borders. It did not try to control interstate commerce.

Notable Dissent.

Justices John Harlan and Joseph Bradley disagreed with the majority. They argued that the Mississippi law did affect interstate commerce and thus violated the Commerce Clause. Justice Harlan also asked how the Louisiana law from Hall v. DeCuir was an unconstitutional violation of the Commerce Clause while this Mississippi law was not.

Why Does It Matter?

The majority ruling reversed the decision in Hall v. DeCuir. The court expanded states’ powers to control business conducted within their borders. Specifically, the ruling established a set of circumstances in which state-mandated racial segregation was constitutionally permissible.

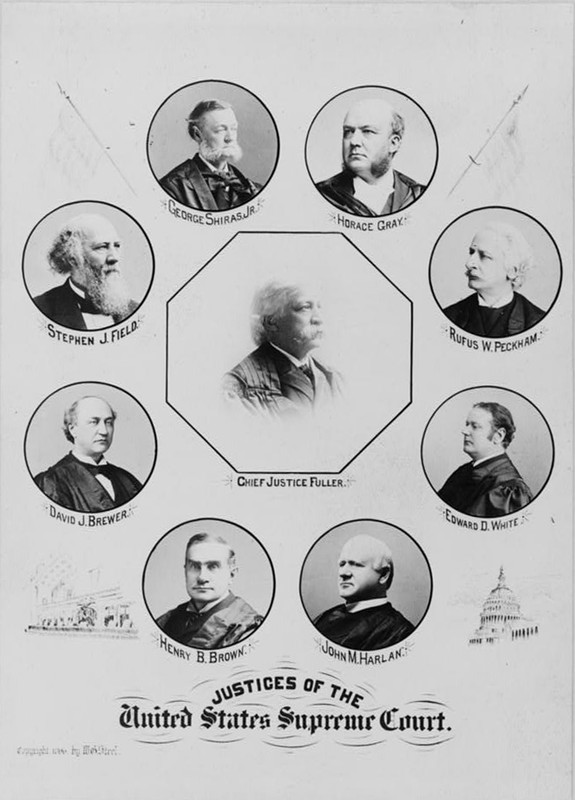

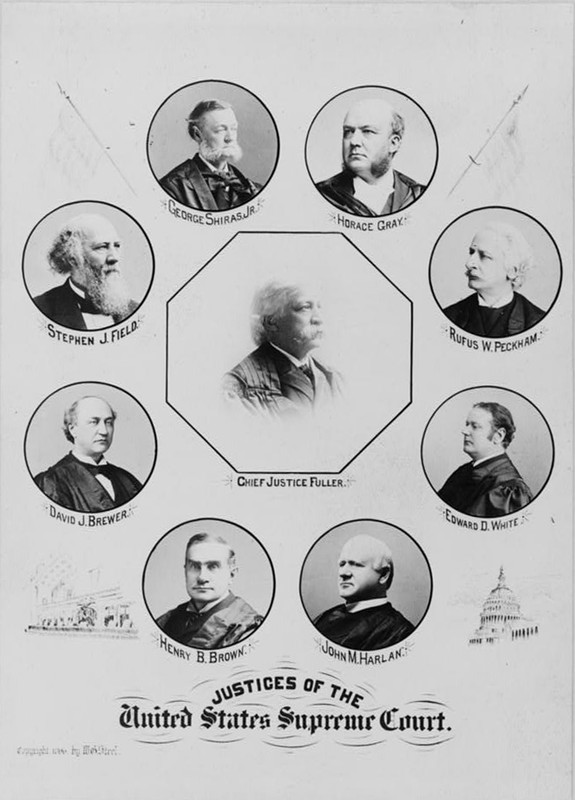

Plessy v. Ferguson

May 18, 1896

In 1890, Louisiana passed the Separate Car Act. This law required railway trains to have separate passenger cars for blacks and whites. These cars were supposed to be of equal quality. On June 8, 1892, a man named Homer Plessy bought a ticket for the East Louisiana Railway. He tried to sit in the white passenger car but the conductor refused access to him. Plessy was mixed race and therefore had to sit in the black passenger car. He did not move to his assigned seat so the police arrested him. He faced legal trial in the District Court of Orleans and was found guilty. Plessy believed that the Separate Car Act was unconstitutional so he challenged the court’s ruling. His case made it all the way to the Supreme Court of the United States in April 1896 as Plessy v. Ferguson. Ferguson referred to John H. Ferguson, the judge in Plessy’s first trial.

The Issue.

Was a state law that required racial segregation on railroad trains constitutional?

The Ruling.

The Supreme Court announced its decision in May of 1896. Seven of the eight participating justices sided with Ferguson and asserted that the Separate Car Act was constitutional. Justice Henry B. Brown wrote the majority opinion. The court decided that the law did not violate the Thirteenth Amendment. The mere suggestion of a legal difference between the races did not have any real effect on the legal equality of the races. The ruling found that this was especially true for differences that could not be hidden, such as the color of one’s skin. Such a legal difference in no way, shape, or form created a condition of slavery.

The Supreme Court majority also disagreed with almost all of the claimed violations of the Fourteenth Amendment. Plessy’s side argued that one aspect of discrimination was the suggested inferiority of one group to another. The court responded that laws requiring the separation of races do not suggest any form of inferiority. Furthermore, Justice Brown added that the only reason segregation may imply inferiority was “solely because the colored race chooses to” believe it does. As the court made clear in Strauder v. West Virginia (1880), there was also a legal difference between political equality and other forms of equality. The court maintained that the Constitution only protected political equality. Racial segregation was not a matter of political equality so it was not protected by the Constitution.

Next, the Supreme Court argued that states do have the power to require racial separation. States had long used their right to police power to enforce segregation in many areas, especially in schools. The court’s ruling in the Civil Rights Cases (1883) showed that segregation did not go against any of the rights or immunities in the Fourteenth Amendment. The ruling in Louisville, New Orleans & Texas Ry. Co. v. Mississippi (1890) also showed that train car segregation did not count as interstate commerce. So it was easy for the court to see that states could pass segregation laws as long as they only affected places inside the state. The East Louisiana Railway Line did not go beyond the borders of Louisiana. Thus, the state was entirely within its right to pass the Separate Car Act.

However, the Supreme Court also wanted to limit the reach of police power. Justice Brown wrote that any state use of police power must be reasonable. By “reasonable,” he meant that the overall public benefit of police power must be greater than the harm it may cause any particular group of people. He listed San Francisco’s laundry law from Yick Wo v. Hopkins (1886) as an example of an unreasonable use of police power. But he highlighted Louisiana’s Separate Car Act as an example of a perfectly reasonable law. The public good from the law was maintaining peace between the races on trains. The law also made sure that people who did not want to share a car with members of the other race did not have to do so. The court’s majority argued that the only harm of the law was limiting people’s freedom to pick which car they sat in. In the court’s view, this harm did not outweigh the benefits.

Notable Dissent.

Justice John Marshall Harlan was the only member of the Supreme Court who agreed with Homer Plessy. His opinion was based largely upon four factors.

1) The Separate Car Act did try to control interstate commerce. In previous cases, the Supreme Court ruled that all railroads counted as public highways. This label meant that only the national government had the power to make laws about railroads. This was a right which the Constitution specifically gave Congress and Congress alone. The state of Louisiana lacked the power to pass this law.

2) The Separate Car Act interfered with the personal freedom of railroad passengers. In a free land, a white person may choose to sit next to a black person. It is their right to do so. No state or national government has the power to take away that freedom from its citizens. Laws requiring racial segregation meant that people were no longer free to choose where they want to sit.

3) Reasonableness is not a good standard by which to judge a law. Justice Marshall asserted that governments either had the power to pass a law or they did not. Letting courts decide what was reasonable would mean that people’s personal opinions become important. However, the role of the court is to be an impartial judge and to make rulings based solely on the law.

4) The United States Constitution is color-blind. By this, he meant that the color of one’s skin should never affect what rights and protections they have. Louisiana’s Separate Car Act required that train passengers be treated separately only because of their race. In Justice Marshall’s opinion, the Constitution did not allow racial discrimination like this.

Why Does It Matter?

The Supreme Court’s ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson was a landmark case in the fight for civil rights. It okayed many states’ efforts to continue discriminating against people of color even after the U.S. outlawed slavery. Overt racial discrimination also become fair game as long as states followed the “separate but equal” doctrine.