Last updated: January 14, 2026

Article

Cuming Sisters: "She-Merchants" of Boston

Witnesses to Revolution

The sisters peered out their window on Boston's Queen Street, too stricken to fathom the significance of the horrid spectacle playing out on the night of October 28, 1769.

"[Screaming]" and enraged respectable gentlemen chased and nearly killed a controversial newspaper publisher. On the heels of this narrow escape, a thousand-strong mob tarred and feathered a bloodied customs service employee "befor[e] [the sisters'] [door]."[1] The night's events made clear that the women were no longer safe, even in their home.

"Vuë de Boston. Prospect der König Strasse gegen das Land Thor zu Boston Vuë de la Rue du Roi vers la Porte de la Campagne a Boston / / gravé par Francois Xav. Habermann." Library of Congress

Violent street politics such as these culminated during the Boston Massacre on March 5, 1770. In the wake of Parliament's 1767 Townshend Acts, which levied customs duties on key imports to the colonies, explosive factionalism split Boston. Starting in March 1768, a new Committee of Merchants campaigned to halt the importation of British consumer goods.[2]

The Cuming Sisters

Elizabeth and Ame (pronounced "Amy") Cuming, small-scale entrepreneurs in their mid-30s who imported fashionable wares from London, found themselves in the middle of the volatile politics of consumption. Elizabeth described their business of selling luxurious accessories as "very trifling." They considered themselves "two industrious Girls who [were] Striving in an honest way to [get their] Bread."[3] Unmarried and without an adult male guardian, they were financially independent and fought to retain that unusual status.

The sisters grew up in nearby Concord. Their parents, natives of Scotland, followed business opportunities in the wake of the increasing flow of trade between Great Britain and the colonies. They were not refugees starting over, rather educated folk from Scotland's upper ranks. Helen Cuming, Ame and Elizabeth's mother, was the daughter of a baronet, a title that placed her family among the British aristocracy (though not the nobility).

Their father died before the twentieth birthday of the elder Ame, and their mother died soon thereafter.[4] Their insufficient age may have prevented their brother John, a recent newlywed on the path to a brilliant career in Concord, from securing them husbands.[5] They did not wish to be wards of their brother and relocated themselves to Boston by 1765.

Shopkeepers and Merchants

In 18th century colonial port communities, anywhere from 2–10% of shopkeepers were women. The ranks of Boston's female entrepreneurs swelled with each passing decade. The number of newspaper advertisements for fashionable imported items sold by women increased.[6]

The Cuming sisters entered a network of Boston women in business. This network nourished their business acumen and provided them with credit, friendship, and social connections.[7] They sold symbols of refinement to gentlewomen of means.[8] They taught fine embroidery at their own school and boarded young ladies from the countryside in their home.[9]

"Faneuil Hall, 1776" Engraved by John C. McRae. Boston Public Library.

Shopkeeping became an increasingly popular means of making a living among both men and women. Shopkeepers started to contract directly with London suppliers, flooding the port markets with an uncontrolled volume of consumer goods.[10] A successful non-importation campaign would, as Massachusetts Royal Governor Francis Bernard observed, "affect middling & little Traders, many of whom must be ruined by it, whilst Men of Great Property & credit might be benefitted by it by becoming Monopolists."[11]

Considered "little Traders" themselves, the Cuming sisters received a shipment of wares in late 1769 of wrought silk, sewing silk, and haberdashery worth 300 pounds sterling. As Governor Bernard knew, livelihoods dependent on constant cash flow and frequently changing fashions would not survive a long-term boycott of British consumer goods. The sisters would be put out of business if they signed a non-importation agreement.

"Enemies to their Country"

In mid-November, Ame and Elizabeth received a visit from the activist arm of the Merchants' Committee. These men knew the sisters planned to sell the £300 shipment from London, "contrary to the [agreement] of the Merchants."[12] The sisters defended themselves against these unwanted visitors with strong words, proclaiming that "[w]e have never [entered] into [any] agreement not to import" and accusing the committeemen of "trying to [injure]" honest businesswomen. Either reluctant to use violent tactics against women or mere messengers, the men left with a threat that the young women "must [take] the [consequences]" of their defiance.[13]

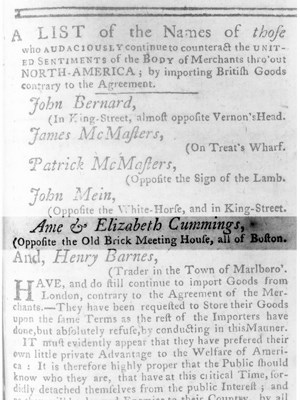

These consequences entailed a very public outing on the front page of Boston's newspaper of protest, the Boston Gazette. The Merchants' Committee denounced the Cumings as "enemies to their country" who "preferred their own little private Advantage to the Welfare of America."[14] By Christmas, every Whig-leaning newspaper had added the Cumings sister to their list of heretics.

On March 19, 1770 Boston's Town Meeting voted that the sisters and nine others be "[entered] on the Records of this Town that POSTERITY may know who those Persons were that preferred their little private Advantage to the common Interest of all the Colonies […]; who not only deserted but opposed their Country in a struggle for the Rights of the Constitution."[15] The price to be paid for financial independence was too high. The Cuming sisters retreated to their small property in Concord.

Driven from Boston

Though the Merchants' Committee and those who enforced its aims never explicitly targeted Boston's "she-merchants," their niche position in that world of commerce guaranteed that women shopkeepers were vulnerable to the pressures of the boycott. Boston’s volatile politics drove the Cuming sisters from the port city. Elizabeth and Ame departed besieged Boston with the Regular Army troops and over 1,000 Loyalist refugees in March 1776. As they watched Boston disappear from view, the ten years they invested in attaining their own version of independence must have appeared wasted.

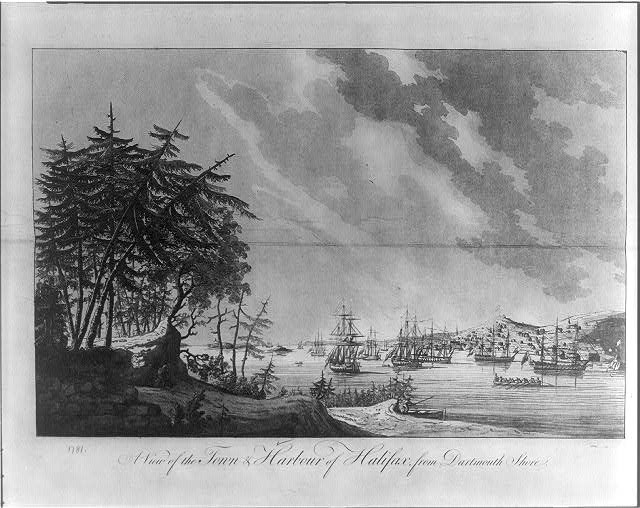

"A view of the town & harbour of Halifax, from Dartmouth shore," published 1781. Engraved by Joseph F. W. Des Barres. Library of Congress.

While the sisters did not understand themselves as political Loyalists, their insistence on their right to chart their fate as individuals irrevocably landed them in the Loyalist camp. They settled in another port town: Halifax, Nova Scotia. There, again with the support of their friends, they made a new beginning. By 1780, "the Miss Cumings [were] well and doing well, by being thrown hither they [had] fallen on their feet and [were] more prosperous than ever they were in Boston."[16]

Footnotes:

[1] Letter, Elizabeth Cuming to Elizabeth Murray, 20 November 1769, Massachusetts Historical Society. Original quotes read as follows: "Skreeming;" "aranged themselves befor the Dorr."

[2] Two perspectives: John W. Tyler, Smugglers and Patriots: Boston Merchants and the Advent of the American Revolution (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1986); Russell Bourne, Cradle of Violence: How Boston's Waterfront Mobs Ignited the American Revolution (Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons, 2006).

[3] Letter, Elizabeth Cuming to Elizabeth Murray Smith, Dec. 23, 1769, Christian Barnes letterbook. Papers of Mrs. Christian Barnes, Library of Congress. Original quote reads "two industrious Girls who ware Striving in an honest way to Git there Bread."

[4] Caitlin Hopkins, "Massachusetts Archives and Commonwealth Museum," Vast Public Indifference, http://www.vastpublicindifference.com/2009/04/, accessed 10/17/2021; Elise Lemire, Black Walden: Slavery and Its Aftermath in Concord, Massachusetts (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009), p. 180; Mary Beth Norton, Liberty’s Daughters: The Revolutionary Experience of American Women, 1750-1800 (Ithaca & London: Cornell University Press, 1996 (1980)).

[5] In Black Walden, Elise Lemire shares a great deal of information about brother Col. John’s high social standing in Concord – as well as about the people he held enslaved.

[6] Mary Beth Norton, Liberty's Daughters: The Revolutionary Experience of American Women, 1750-1800 (Ithaca & London: Cornell University Press, 1996 (1980)).

[7] Patricia Cleary, Elizabeth Murray: A Woman’s Pursuit of Independence in Eighteenth Century America (Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2000).

[8] For a peek into the Cuming sisters' shop, see "Ame & Elizab Cuming inform their customers," Boston Gazette, 11 November 1765, The Annotated Newspapers of Harbottle Dorr, Jr. Massachusetts Historical Society, http://www.masshist.org/dorr/volume/1/sequence/273, accessed on 10/17/2021.

[9] Robert Francis Seybolt, The Private Schools Of Colonial Boston (Harvard University Press, 1935), p. 70; Pamela Parmal, "Fashionable Accomplishments: Faith Trumbull Huntington." In Women’s Work: Embroidery in Colonial Boston (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 2012). A family coat of arms with gold and silver thread completed in this school is shown in Robert Shaw, The Instruction Of Young Ladies: Arts From Private Girls’ Schools And Academies In Early America https://www.incollect.com/articles/the-instruction-of-young-ladies-arts-from-private-girls-schools-and-academies-in-early-america.

[10] Cleary, Elizabeth Murray; T. H. Breen, The Marketplace of Revolution: How Consumer Politics Shaped American Independence (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004).

[11] Colin Nicolson, "Governor Francis Bernard, the Massachusetts Friends of Government, and the Advent of the Revolution." In: Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, 1991, Third Series, Vol. 103 (1991), pp. 24-107, 109-113.

[12] For more on the Merchants' Committee, see: Charles M. Andrews, The Boston Merchants and the Non-Importation Movement (Cambridge: J. Wilson & Son, 1917), https://archive.org/details/cu31924030152437. Original quote reads as follows: "contrary to the aggremant of the Merchants."

[13] Letter, Elizabeth Cuming to Elizabeth Murray Smith, Dec. 23, 1769, Christian Barnes letterbook. Papers of Mrs. Christian Barnes, Library of Congress. Original quotes read as follows: "[w]e have never antred into eney agreement not to import;" "trying to inger;" "must tack the Conciquances of their defiance."

[14] "A List of the Names of those who AUDACIOUSLY continue to counteract the UNITED SENTIMENTS of the Body of Merchants [… ]," Boston Gazette, 22 January 1770, The Annotated Newspapers of Harbottle Dorr, Jr. Massachusetts Historical Society, https://www.masshist.org/dorr/volume/3/sequence/61.

[15] This assault started on the front page of each week’s edition of the 1769 Boston Gazette. Names and addresses were listed and called "enemies to their country" who "preferred their own little private Advantage to the Welfare of America." Anyone purchasing from them "must expect to be considered in the same disagreeable light." Norton, Liberty's Daughters. See also Pauline Meier, From Resistance to Revolution: Colonial Radicals and the Development of American Opposition to Britain, 1765-1776 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 1972), pp. 128-129. Original quote reads as follows: "entred on the Records of this Town that POSTERITY may know who those Persons were that preferred their little private Advantage to the common Interest of all the Colonies […]; who not only deserted but opposed their Country in a struggle for the Rights of the Constitution."

[16] Caitlin Hopkins, "Enemies to their Country," Vast Public Indifference, http://www.vastpublicindifference.com/2009/10/enemies-to-their-country-essay.html, accessed 10/17/2021. Original quote reads as follows: "the Miss Cumings are well and doing well, by being thrown hither they have fallen on their feet and are more prosperous than ever they were in Boston."