What happens to a forest when yellow-cedars experience a die-off? How healthy are Glacier Bay’s yellow-cedars?

Project Dates

Field work 2011-2013; data analyses and reporting through 2015.

Did You Know?

Yellow-cedar mortality affects about 500,000 acres of Southeast Alaska’s Tongass National Forest. Recent studies implicate factors related to climate change as key drivers of yellow-cedar decline.

Introduction

Yellow-cedar, a tree species of high cultural, economic and ecologic value, has been dying off in British Columbia and Southeast Alaska since the late 1800s. The roots of yellow-cedar grow close to the ground surface and are very susceptible to freezing in periods of low insulative snow cover. Tree death peaked in the 1970s and 1980s—a period marked by warmer winters, reduced snowpack, and severe temperature fluctuations in the spring.

Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve sits within the northern extent of yellow-cedar distribution and protects intact, live yellow-cedar stands at the current latitudinal limit of decline. Cedar stands to the south are declining in health. With continued climate warming, yellow-cedar in the park could be vulnerable. Much research on yellow-cedar decline has focused on understanding the causal mechanisms, but a species dieback can have cascading effects on the surrounding forest community as well. Patterns of succession can indicate the future composition and structure of affected forests.

This study dovetails with ongoing U.S. Forest Service (USFS) research. It examines questions such as: As yellow-cedars die, what species regenerate? What are the changes in stand structure and the community composition of conifer species? What are the effects on understory plant diversity? The study also provides an assessment of the current status of yellow-cedar populations within park boundaries. Increasing knowledge of how the forest structure responds to yellow-cedar decline may provide insights into possible future changes in the park.

Methods

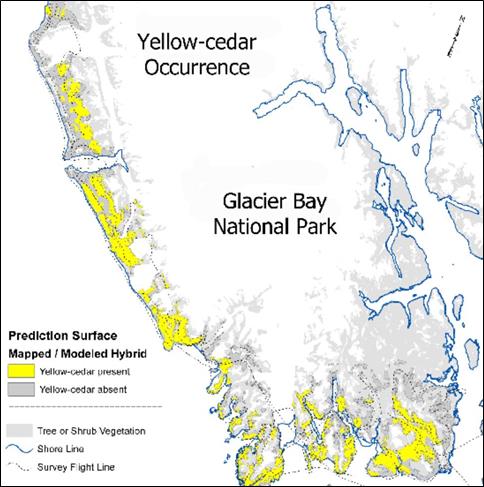

Aerial surveys were conducted during the summers of 2011 and 2012 to map the presence of yellow-cedar throughout Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve and to assess the south-to-north trend of mortality on Chichagof Island (to the south of the park). Researchers conducted ground-based vegetation surveys in live yellow-cedar forests within the park and across a chronosequence of forests affected by decline at various periods on Chichagof Island. This study design was used to make comparisons in the regeneration, conifer community structure, and understory dynamics between unaffected yellow-cedar forests and those affected by decline across time and space.

During the spring of 2013 a series of semi-structured interviews were conducted with forest users and managers to understand the ways in which people value and use the forests and the ways in which the decline may influence patterns of resource use and priorities for forest management. The information generated from these interviews, combined with results from the ecological aspects of this study on succession, will contribute to our understanding of the important cultural, economic, and ecological values of these vulnerable forests.

Findings

USFS aerial surveys showed yellow-cedar occurrence on an estimated 60,000 acres of land within Glacier Bay National Park. At present, the cedar stands within the park are healthy.

Preliminary findings from plot data indicate a dynamic forest community response that occurs in stages as yellow-cedar declines. Understory plants gain access to light and nutrients as trees die and the canopy opens. At sites where the most time had passed since the onset of decline, no yellow-cedar saplings were observed, suggesting a change in the conifer composition of the forest. The researchers are still completing analyses to understand this and other complex overstory and understory dynamics in forests affected by yellow-cedar decline. These dynamics may also have implications for wildlife due to changes in forage and habitat.

Learn More

The U.S. Forest Service website has a wealth of information.

https://www.fs.fed.us/pnw/research/climate-change/yellow-cedar/yellow-cedar_and_climate_change.pdf

https://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/r10/forest-grasslandhealth/?cid=fsbdev2_038830

Lauren Oakes has written a blog about her research for the New York Times. http://green.blogs.nytimes.com/author/lauren-e-oakes/

Last updated: October 26, 2021