On March 10, 1902, William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody penned a letter to Curtis L. Hinkle, chief clerk of the Wyoming State Board of Land Commissioners, while in Chicago, en route to the Hoffman House, a leading New York City hotel. Although he was traveling east on business, Cody’s entrepreneurial instincts drove his thoughts out West, where he was making plans for a massive irrigation project in Wyoming – the Cody and Salsbury Canal. Although in the midst of orchestrating his long-running Wild West shows, Cody assured Hinkle, “I am useing [sic] my best energy to get that Canal built.” In fact, Cody and his partners with the Shoshone Land and Irrigation Company had been working for a number of years to line up investors for the canal, which they envisioned would use water from the Shoshone River to irrigate the arid lands of northwestern Wyoming’s Bighorn Basin. Cody also foresaw a “great powerplant to turn the wheels of industry.”

It wasn’t until the 1890s, following passage of the Carey Act, that a significant number of people began to settle Wyoming’s Bighorn Basin. The Carey Act made Federal lands available for private development, as long as projects were state supervised and the lands irrigated and occupied. With his Wild West show partner Nate Salsbury, Cody took advantage of the Carey Act to “withdraw” 60,000 acres near the town of Cody he hoped to develop as an irrigation project, and acquired water rights from the Shoshone River to irrigate that land. In 1903, when it became clear that Cody could not raise the money to build his canal, the Wyoming State Board of Land Commissioners cancelled the land withdrawal and turned to the Federal Government to build an irrigation project. In 1904, Cody transferred his water rights to the Secretary of the Interior, and in 1905 the U.S. Reclamation Service (today’s Bureau of Reclamation) began to build Shoshone Dam, now known as Buffalo Bill Dam. The dam would be the keystone for Reclamation’s Shoshone Project, which would ultimately open about 90,000 acres in northwestern Wyoming to irrigated farming.

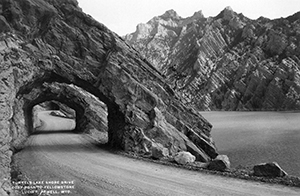

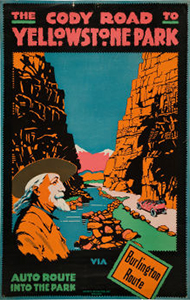

A V-shaped, narrow, steep-walled canyon along the Shoshone River 6 miles west of the town of Cody drew the attention of Reclamation engineers as the perfect site for the new dam. At the onset of the project, crews carved a road through the rugged terrain to the dam construction site. (After the dam was completed, this road was expanded west to connect with the route to Yellowstone National Park. This scenic stretch of road was heralded as the “most wonderful 90 miles in America,” and became part of the National Park Service’s Park-to-Park Highway system, which was established in 1920.)

When completed in 1910, the dam reached a record-setting height of 325 feet. Reclamation had built the dam using only hand labor, teams of horses, and steam-powered equipment – no hydroelectric plant was built to aid in its construction. But the great height of the completed dam provided enough vertical “drop” to develop hydroelectric power, and Reclamation needed electricity for Shoshone Project purposes. The bureau also planned to market excess power to project towns and businesses. (It was common practice for Reclamation to build powerplants for its own construction projects and irrigation facilities, and then sell excess power to help repay project costs.) Preliminary studies for the Shoshone Powerplant, which was to be located 600 feet downriver from the dam, were completed in 1919.

In November 1920, Reclamation crews began to build the Shoshone Powerplant by “force account,” meaning using in-house labor rather than contracting out the work. The harsh conditions inside Shoshone Canyon proved an obstacle. Strong gusts and below-freezing temperatures threatened workers with plummeting ice and rocks. In 1921, water released through the dam spillway flooded construction efforts by crews afloat in rafts on the Shoshone River. With the towering cliffs of the Absaroka Range on one side and a straight drop to roaring waters on the other, the steep canyon concealed the construction zone from tourists motoring along the Cody Road to Yellowstone National Park. In January 1922, the Cody Enterprise reported that the “casual observer would have no idea that there were 135 men employed in the work,” and predicted the powerplant’s completion by the time “the dudes come through to the Park next spring.”

The Shoshone Powerplant was indeed completed later that year, and was Reclamation’s first hydropower plant in Wyoming. The hydroelectricity that was generated immediately benefitted the Shoshone Project. It was used to construct another Project dam, the Willwood Dam, and power was also delivered to the town of Powell. In the spring of 1922, the Powell Tribune announced that “Powell has now become an electrical town.”

The Shoshone Powerplant’s eclectic architecture, built using concrete made from crushed cliffside rock, blended into Shoshone Canyon. Inside, however, control panels, slick tile floors, and two spinning horizontal units generating 1,000 kilowatts of power each filled the space with the sounds and sights of industry. In 1931, a third unit installed at Shoshone increased the total capacity to 6,012 kilowatts.

The Shoshone Powerplant harnesses the energy in the Shoshone River, where flows begin with snowmelt of the Absaroka Mountains in Yellowstone National Park. The water stored behind Buffalo Bill Dam forms an artificial lake, the Buffalo Bill Reservoir. An intake structure located upstream of Buffalo Bill Dam controls the flow of water from the reservoir into a penstock, which is a pipe or tube that funnels the water directly into a turbine within Shoshone Powerplant. The powerful rush of water rotates the turbine blades, which starts the generator. The electric current generated at Shoshone then travels to a transformer, where the voltage – which is the pressure that pushes the current over a wire – is stepped up, transmitting the charge over miles of wire.

Although providing momentary points-of-interest for passersby to Yellowstone National Park, the Buffalo Bill Dam and Reservoir and Shoshone Powerplant principally provide economic stability for residents of the northern Bighorn Basin. The modern benefits of electricity in rural Wyoming boosted nearby development and industry, just as Buffalo Bill Cody envisioned prior to the U.S. Reclamation Service’s Shoshone Project.

In March 1980, Reclamation decommissioned the Shoshone Powerplant because its turbines had deteriorated from more than 50 years of use. However, in 1991, the plant was brought back online after a modern 3-megawatt unit replaced the decommissioned 1931 unit. The two original 1923 units, although no longer in operation, were left in place within the powerhouse.

In 1985, Reclamation entered into a joint venture with the State of Wyoming to raise the crest of Buffalo Bill Dam by 25 feet, with aeration piers and a new walkway adding an additional 15 feet. Construction began in 1988 and was completed in 1992. Raising the crest of the dam created additional reservoir storage capacity to replace original capacity lost to sedimentation, as well as new capacity that is available to the State to market in the future. The increased height also provided the necessary head for an additional powerplant, the Buffalo Bill Powerplant, followed by the Spirit Mountain Powerplant in 1994. Together with the Heart Mountain Powerplant, which was completed in 1948, this brought the total number of power facilities on the Shoshone Project to four. Today, the Shoshone Project generates up to 30.5 megawatts of power at its four powerplants, and is integrated into the Pick-Sloan Missouri Basin Program, a massive program under which Reclamation and the Corps of Engineers have built facilities that develop the Missouri River Basin’s water resources to provide power to a 10-state region.

Visit the National Park Service Travel Bureau of Reclamation's Historic Water Projects to learn more about dams and powerplants.

Last updated: January 13, 2017