What do you imagine when you hear of “The West” or “the American Frontier”? Is it wide open spaces? A lone cowboy? John Wayne?

Thanks to decades of western books and movies, the American West has become a place of mythological significance—a place where “Go West, young man” was advice for those seeking to find fortune and prove their bravery and independence. In other words, “going West” would show that you were a man who could live up to American values.

So where were the women?

There are a few female figures that appear in this narrative, like Annie Oakley of the Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show fame. At the time of westward expansion —the mid-1800s—there were fewer opportunities for women. The addition of vast areas to the United States through Louisiana Purchase and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo opened the way for settlers, who felt it was their right to claim land. Men often went in advance of their wives and families to establish a property and income. Women are commonly portrayed as having been dragged along on these adventures.

Women’s historical perspectives can change this perception. Certainly there were those whose stories went like this: “Well, the wife got tired of it and walked out one night and left the country.” (Such is the tale from an oral history given by one early settler of the area that is now Joshua Tree National Park.) However, other women made an empowered choice to go to, and stay in, the desert. This is demonstrated by two prominent women in the park’s history: Frances Keys and Elizabeth Campbell.

Frances Keys

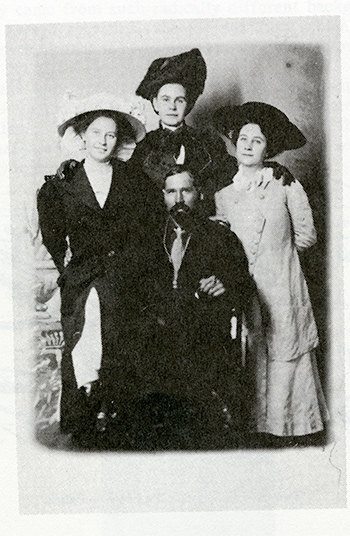

Frances Mae Lawton grew up in Canada and Los Angeles before marrying Bill Keys and moving to Keys Ranch in the 1920s (part of which was a homestead originally belonging to Bill’s grandmother!). One family friend recalls, “Mrs. Keys was a lady. I think she had been raised in a rather sheltered life. But she adapted herself so well to the life out there. …” Photos of a young Frances show a fashionably-dressed woman who was a stenographer for Western Union. She could have continued this work, but chose the no-frills life of the ranch instead. It was demanding, but must have suited her as she stayed at the ranch into advanced age. She assisted with Bill’s mining, washed clothes, butchered meat, canned produce, and taught the children before a school house was built and a woman teacher hired. Those who knew her always remarked that she took great care of her complexion, wearing a bonnet outdoors. These were so popular that she eventually sold them at a small store, her own venture which she opened next to the ranch house.

Elizabeth Campbell

Elizabeth Warder Crozer was born into a wealthy family in Pennsylvania, where she had a French tutor and attended private school. She even went to finishing school where young ladies were usually trained to enter society, while Elizabeth was prepped for college. During WWI she served as a nurse and cared for William Campbell, a soldier who had been exposed to mustard gas. Against the wishes of her family, the two married and moved to the desert for William’s health. While in the Twentynine Palms area, they both became fascinated with the prehistory of the area and dedicated the rest of their lives to archeology, making significant contributions to the field. Elizabeth later wrote a biography called Desert Was Home. She relates how she first resisted permanently relocating to the desert, but that ultimately found her vocation there.

These women were not marginalized in their own time, but have been somewhat covered up by history. The National Park Service has responded to this larger issue with a women’s history initiative called “Telling the Whole Story: Women and the Making of the United States,” launched in 2012. Joshua Tree National Park is also engaged with the fifteen federally-recognized tribes with cultural affiliation to these lands. Ethnographic studies and additional oral histories will help to reflect the diversity of heritage encompassed by the park.

Last updated: June 22, 2020