Not All Who Wander are Lost: Following the Dispersal of Alaskan Wolves

NPS Photo / Tim Raines

Wildlife biologists have long known that wolves sometimes travel great distances in search of new mates and ranges. However, modern GPS-based wildlife tracking now allows researchers to follow in the very footsteps of wolves as they travel across vast and wild landscapes. Alaska National Park scientists have witnessed some surprisingly intimate interconnections between wolves, parks and people by using this technology over the last few years.

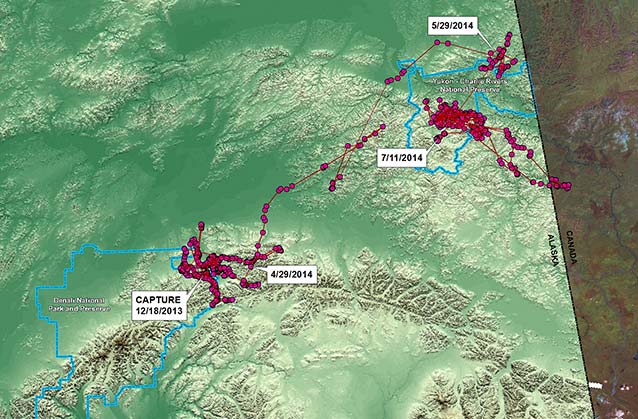

Wolf 1308GM

On December 18, 2013, Denali National Park biologists collared a four-year-old male wolf from the Denali East Fork pack for the purpose of comparing his movements to that of local coyotes. However, 1308 traveled in a direction that no one anticipated. In May 2014, he traveled more than 200 miles as the crow flies to just north Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve in eastern Alaska. Two months later, he moved into the vacated home range of the 70 Mile pack in the center of the preserve.

During a tracking flight in late September, 1308 paired up, presumably with a female wolf. Shortly thereafter, wolf 1308 traveled into Canada apparently following the Fortymile caribou herd, before returning to Yukon-Charley Preserve where he appear to be settling into the home range that the 70 Mile pack previously inhabited.

Wolf 1308's journey to Yukon-Charley National Preserve might seem like an arbitrary move, but shows a connection between two remote Alaskan parks that might not have been witnessed without the use of GPS collars.

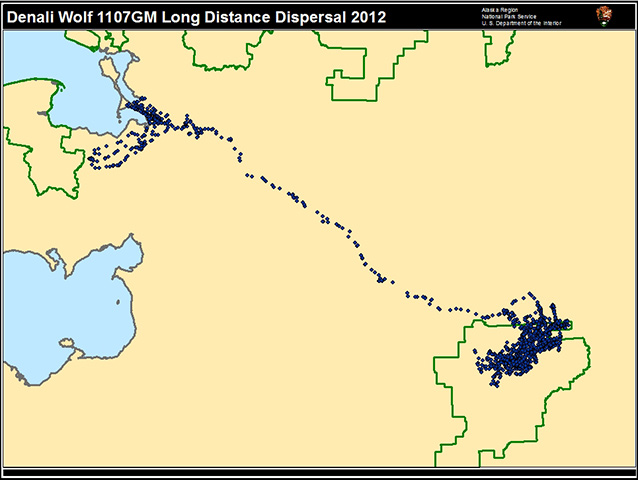

Wolf 1107GM

On March 11, 2011, Denali National Park biologists collared a 10-month-old grey male of the McKinley Slough pack for the purpose of watching his movements in relation to the Denali Park Road. In June of 2012, 1107 left the park and started an incredible journey towards Bering Land Bridge National Park on the Seward Peninsula.

The collar that the wolf wore recorded his location every three hours for two years before releasing automatically on September 19, 2012. When the collar dropped about 100 miles southwest of Kotzebue, park researchers retrieved it and discovered that 1107 had a poignant human dimension as part of his wanderings.

The pilot who picked up the collar had been out hunting a few weeks prior and had heard a lone wolf howling close to his camp. When he reviewed the coordinates for the collar, he discovered that 1107 was less than a mile from his hunting camp on the night that he was there. This could mean that the pilot heard 1107 around the time the collar fell off.

Hearing a wolf howl is a powerful event for any individual and can invoke the feeling of being in true wilderness. Wolf 1107’s travels may have conjured that feeling for people from Denali to Bering Land Bridge.

The dispersal of wolves such as 1308 and 1107 illustrates that modern technology has greatly improved our understanding of wildlife populations that range across huge geographic areas. GPS collars prove that Alaskan wolves know no bounds, and through their travels, create significant connections between America's public lands.

Tags

- bering land bridge national preserve

- denali national park & preserve

- yukon - charley rivers national preserve

- wolf dispersal

- research highlights

- murie science and learning center

- wolves

- yukon-charley rivers national preserve

- bering land bridge national preserve

- denali

- wildlife

- dena

- science summary

- biological resources

- alaska

Last updated: November 17, 2022