Last updated: March 4, 2025

Article

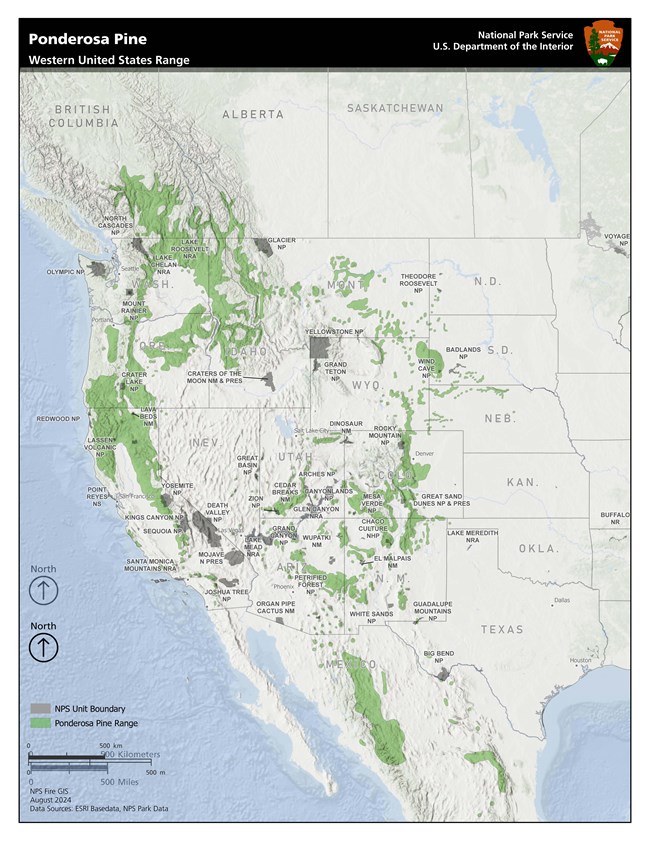

Wildland Fire in Ponderosa Pine: Western United States

NPS

Ponderosa pine is a large coniferous (cone bearing and evergreen) tree. It is the dominant tree in a ponderosa pine forest, or one of many species in a mixed conifer forest, particularly in combination with Douglas-fir. The typical surface cover in a ponderosa pine forest is a mixture of grass, forbs and shrubs. This forest community generally exists in areas with annual rainfall of 25 inches or less. It has the widest geographical range of the pine species in North America. Its range extends as far north as Canada and as far south as Mexico and from Nebraska to the Pacific Coast. Extensive stands of ponderosa pine forest are in the southwestern United States, central Washington and Oregon, southern Idaho, and the Black Hills of South Dakota and Wyoming.

For approximately the first five years of their life cycle, ponderosa pine seedlings must compete strenuously with grass cover for survival and are very susceptible to fire. But, beginning in the fifth year or sixth year of its life, the tree begins to develop thick bark and deep roots and sheds its lower limbs. These factors increase its ability to withstand fire and decrease the possibility of a fire climbing to the crown. Furthermore, a thick bed of needles is deposited on the ground, suppressing grasses in the vicinity, thereby controlling the type of fuel available for burning and the type of fire that the tree may need to endure in the future.

NPS

Conifers, including ponderosa pine, are most flammable in the spring when their old needles are dry and new needles have not yet grown. In the fall, when the needles have dried out, conifers again are susceptible to fire.

Historically, fires in ponderosa pine communities burned naturally on a cycle of one every 5 to 25 years. This frequent fire burned the grasses, shrubs, and small trees, and maintained an open stand of larger ponderosa pine trees.

Fire is essential to shaping and maintaining ponderosa pine forests. Historic ponderosa pine forests supported frequent, low intensity surface fires. However, they also experienced some larger and more severe fires. These forests contained a full range of trees of different ages - from young seedlings, to mid-story trees, and larger overstory trees. There were few understory and mid-story trees. Scattered large diameter ponderosa pines created an open forest and canopy. Light could reach to the forest floor, and many grasses and forbs grew in the understory. From time to time, low-level fires burned forest surface fuels, such as branches, twigs, pine cones and dead vegetation.

Prescribed burning is applied with slightly greater frequency and regularity, keeping in mind that a fire that is ignited too early will not have sufficient fuel to be effective. Similarly, a fire ignited too late in the cycle may potentially develop into a high-intensity fire.

NPS

In the early 1900s, land managers began putting out fires, leading to almost no natural wildfires. After more than one hundred years of fire suppression, ponderosa pine forests have changed. Where there used to be trees of different ages, there are now many seedlings and midstory trees. Large diameter ponderosa pines are now competing for resources, such as nutrients, light, and water.

Left image

Pre-treatment monitoring plot within the restoration unit at Mount Rushmore National Memorial.

Credit: NPS

Right image

Post-treatment monitoring plot within the restoration unit at Mount Rushmore National Memorial. Pole-sized tree density was reduced by more than 95%.

Credit: NPS

Tags

- bandelier national monument

- big bend national park

- big hole national battlefield

- bighorn canyon national recreation area

- black canyon of the gunnison national park

- bryce canyon national park

- carlsbad caverns national park

- chiricahua national monument

- coronado national memorial

- crater lake national park

- devils tower national monument

- el malpais national monument

- el morro national monument

- florissant fossil beds national monument

- gila cliff dwellings national monument

- glacier national park

- grand canyon national park

- great basin national park

- great sand dunes national park & preserve

- guadalupe mountains national park

- jewel cave national monument

- lake roosevelt national recreation area

- lassen volcanic national park

- mesa verde national park

- montezuma castle national monument

- mount rushmore national memorial

- nez perce national historical park

- north cascades national park

- rocky mountain national park

- saguaro national park

- sequoia & kings canyon national parks

- theodore roosevelt national park

- tonto national monument

- tuzigoot national monument

- valles caldera national preserve

- walnut canyon national monument

- whiskeytown national recreation area

- wind cave national park

- wupatki national monument

- yosemite national park

- zion national park

- prescribed fire

- wildland fire

- fire facts

- fire in ecosystems

- arizona

- new mexico

- california

- colorado

- utah

- nevada

- nebraska

- south dakota

- north dakota

- wyoming

- montana

- idaho

- oregon

- washington

- fire ecology

- ponderosa pine

- jmrlc

- fire

- forestry

- natural resources