Introduction

National Park Service

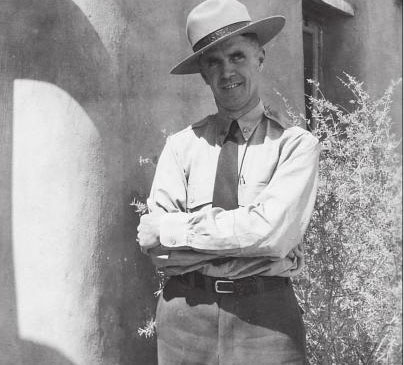

With the passing of two generations since the end of the Second World War, scholars of the National Park Service are now fashioning the context of life at units like White Sands National Monument. What emerges is both the continuity of issues (economic, political, and ecological) that shaped the park, as well as the patterns of change that rendered the monument distinctive within the national park system. White Sands owes its early history to two men. Often referred to as the Father of White Sands, Tom Charles fine-tuned the late New Mexico Senator and later Secretary of the Interior Albert Falls's vision of a yearlong playground. Johnwill Farris would become the “second caretaker” or the first designated superintendent of White Sands NM.

During World War II, Johnwill Faris and his small staff would endeavor to provide the visiting public with the aesthetic and recreational experiences that they had come to expect from the dunes. Yet the vagaries of war surrounded White Sands in ways that few other NPS units could imagine. From this emerged a conflict between preservation and development that would persist for the next five decades, only shifting course as the nation in the 1990s faced the duality of declining economic activity and the demise of the Cold War.

White Sands owed its creation to policies crafted in the Great Depression and subsequent New Deal. By 1940 the monument possessed the boundaries and structures that would entertain millions of guests throughout the second half of the twentieth century. Yet the changes brought to the American West by the entry of U.S. forces into war guaranteed that White Sands would remain one of the most-visited parks in the NPS network. Gerald Nash has written that by 1945 "the West had become a barometer of American life." Ten million men and women passed through the region as members of the armed services, while millions more civilians flocked to the West's myriad of defense installations and industrial centers. The Tularosa basin, while not growing on the scale of Albuquerque or El Paso, nonetheless witnessed a large in-migration of service personnel and their families to the Alamogordo Army Air Base (AAAB). The same conditions of environment that had made White Sands so exotic and forbidding in the 1930s (isolation, distance, aridity, and hot temperatures) suddenly became attractive to the Roosevelt administration's military strategists. The War Department would thus transform southern New Mexico in the space of three short years, and alter the course of White Sands' history.

President Roosevelt’s Social Policies and Wartime Strategies

National Park Service

Three weeks after Pearl Harbor, Interior secretary Harold Ickes initiated the process of change that would fundamentally alter the history of White Sands. Ickes, under whose purview fell not only the NPS but also much of the public land in the Tularosa basin, recommended to President Roosevelt that the Army's request for 1.25 million acres in southern New Mexico be approved. Nearly 275,000 acres of the bombing range belonged to the state of New Mexico, and almost 35,000 more acres had been claimed by private citizens. Ignoring the complex negotiations of 1941 that had "resolved" the NPS-New Mexico disputes over claimants in the monument, Ickes encouraged FDR to sign Executive Order No. 9029, creating the Alamogordo bombing range. The order contained a clause calling upon the Army to "consult" with Interior officials about bombing targets. In addition, the order promised to restore the lands to Interior "when they are no longer needed for the purpose for which they are reserved."

The future of White Sands, and for that matter the nation as a whole, reached a watershed in the spring of 1945. The Allied offensive in Europe had closed within striking distance of the German capital of Berlin, with victory all but assured by April. That month also the nation lost its four-term president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, whose social policies had fostered the growth of White Sands, even as his wartime strategies engulfed the dunes with military training and visitation. But the most distinctive feature of the entire conflict - the detonation of the atomic bomb - touched White Sands as would no other event in park service history. The sequence of events in the Tularosa basin from April to August 1945 created the "atomic age" tensions that bedeviled the monument for the next five decades, even as the permanent presence of a major air base to the east (Holloman) and the White Sands Proving Ground to the west (later renamed the White Sands Missile Range) buffered the dunes from postwar commercial development that became the core of John Freemuth's "islands under siege" thesis.

It was ironic, therefore, that on the date of FDR's death (April 12), Johnwill Faris called Santa Fe regional headquarters to report that "the [Army] engineers had filed condemnation [papers] on all of the private and state land, not only adjacent to but within the boundaries of the monument." James Lassiter, acting Region III director, assumed that "after the war we should have a good opportunity of having this land [the private in-holdings] transferred to us and added to the monument." Such optimism spread to NPS wartime headquarters in Chicago, where former Region III director Hillory Tolson (now acting NPS director) called upon White Sands to use its water in Dog Canyon so that its permit would be renewed. Soldiers continued to pour into the monument (over 7,000 by June 1), and Johnwill Faris expressed hope that White Sands could coexist with the military despite the dunes' location "in the very heart of the new [bombing] area."

Brave New World

Courtesy White Sands National Monument

The park service could not know the scale of change about to descend upon White Sands, but each passing week in the spring and summer of 1945 revealed a brave new world that challenged Johnwill Faris and his staff. By May the Army Engineers had informed Faris that the extent of test firing might require evacuation of personnel for indefinite periods. Faris learned that the vast stretch of the Tularosa basin (from Socorro to Carrizozo, then south to the Texas state line) had become part of the "Ordcit" project (which Faris for a time called "Ordcet"). On May 28, Faris wrote to Santa Fe NPS officials: "The sands proper are very much in the danger zone. My understanding is that we will be denied any and all use of the sands." Army Engineer appraisers took the monument's "Physical Plant Index" to El Paso to study the extent of NPS facilities that stood in the line of fire. Within days the regional office solicited urgent advice from Chicago, as War Department officials spoke as if "the White Sands are actually going to constitute a bomb target in themselves." E.T. Scoyen, associate director for Region III, underscored this concern with testimony taken from a hearing in Albuquerque of the U.S. Senate Committee on Public Lands. "One is led to conclude that the activity must be of great importance in the conduct of the war," Scoyen wrote to A.E. Demaray in Chicago, as "there could be no other adequate justification for breaking up ranch homes which have been going concerns for well over 50 years with severe financial losses in many instances."

The Army felt confident that it could avoid major damage to NPS facilities at White Sands, but moved nonetheless to secure the park acreage by gaining permission to close U.S. Highway 70 from Alamogordo to Las Cruces. The speed of planning for the atomic test resulted in delays in communications, and also unintended remarks that sustained the levels of anxiety at the monument. On June 4,1945, A.E. Demaray wired Region III with word that the museum need not be dismantled. "We are assured," said Demaray, that the monument was "not a bombing target but merely within [the] path of [the] projectile." Yet the next day, Johnwill Faris reported that a member of his staff, Ray Knabenshue, had spoken with an army captain who said "that unless we [the park service] were out by the 15th [of June] the army would put us out." Faris took Knabenshue's comments seriously, in that he had been well-connected to national leaders prior to coming to White Sands for his health (Knabenshue had been employed by the Wright brothers early in their flying experiments, and his wife had served as personal secretary to FDR while he was governor of New York). The story proved groundless, however, and by June 10 Faris had regained his belief that the postwar era could help rather than hurt the monument. An example was his correspondence with the regional director to plan for "taking in all of the sands area as a postwar movement." Charles Richey had determined that "prevailing winds may move our best sands to lands outside our boundary." The park service should initiate a "complete investigation," and be ready if the acquisition occurred "not in the immediate future, but over a long period of time."

The Manhattan Project and the Nuclear Age

Courtesy Los Alamos Photographic Laboratory

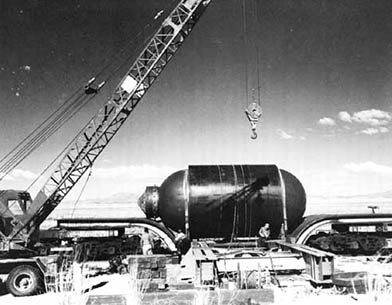

This dream came to an end in July 1945, when the Army Engineers' "Manhattan Project" came south from Los Alamos, New Mexico to detonate the first atomic weapon in human history. When Johnwill Faris learned that White Sands could no longer draw water from the air base because of the project, he realized the scale of the Army's plans. Only two days prior to the July 16 nuclear blast at "Trinity Site," on the White Sands Proving Grounds, Faris discovered that the Army planned not only a twelve-inch waterline from Alamogordo, but also a 115,000-volt power line, and massive airplane runways. "It is a project that is being rushed from all angles," Faris told his Santa Fe superiors, "and things break fast." Then the NPS correspondence became silent on the pace of construction, even though the atomic explosion occurred less than sixty miles northwest of monument headquarters. Thus Faris could not realize how ironic was his letter on August 3 to the regional office protesting the NPS decision to remove the Billy the Kid exhibit from the White Sands museum. Faris, who in 1940 had voiced concern about the park service idolizing such a violent figure where children came to visit , now believed that the early history of the Southwest without Billy was "like the Civil War without [Abraham] Lincoln." Faris had learned in his six years at the dunes that "to a surprisingly large number of people in our southwest Billy the Kid was almost a crusader." To ignore him, "good or bad," said Faris, would now "show a distortion not in keeping with our policy of [portraying] true facts for our visitors."

The need for secrecy lifted on August 6,1945, when press releases heralded the dawn of the nuclear age, and White Sands' place therein. Acting Region III director Scoyen wrote to Chicago NPS officials with an explanation of the impact of the atomic testing on both White Sands and Bandelier national monuments. The Bandelier custodian had once threatened to arrest Los Alamos Army officers engaged in "unauthorized operations," while Johnwill Faris had reported that the nuclear blast on July 16 "was covered up for a time as the explosion of a [munitions] magazine at the air base." Faris' wife Lena, whom Johnwill had sent with their two sons to California just before the test date, remembered in 1993 that the bomb was not only, in the words of historian Ferenc M. Szasz, "the day the sun rose twice" (a reference to the intense glare that pilots saw 600 miles away). The shock waves were also measured 550 miles west of White Sands at the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation office in Boulder City, Nevada. Thus it did not surprise Mrs. Faris that the vacuum created by the explosion awoke Joe Shepperd and his wife, sleeping in their house at the monument, and pulled the covers across their bedroom.

National Monument Proposed – the “Atomic Monument”

Courtesy Los Alamos Photographic Laboratory

For the Alamogordo chamber of commerce, the release of information on Trinity Site provided a unique opportunity for tourism promotion. On the morning of the second atomic blast, over Nagasaki, Japan (August 9, 1945), chamber officials called Johnwill Faris to suggest that the park service create a new national monument to commemorate the atomic test. A.P. Grider and Fritz Heilbron of the chamber wrote to the NPS director to promote the idea, comparing its historical significance to "the spot where the first Pilgrim set foot on this continent." Johnwill Faris saw things somewhat differently, as he dealt more closely with Army officials than did the chamber. "Peace will have no effect on the White Sands Proving Ground operations," he told the regional office. Yet Faris knew that the atomic site held great potential, and suggested that the NPS had "a wonderful opportunity to build and install a museum of super-quality."

The Alamogordo chamber knew what mattered to visitors and locals as the Second World War came to an end. Whether the curious came to the Tularosa basin for a glimpse of "instant" history, or whether local residents wished to rid themselves of the cares of wartime sacrifice, the numbers at White Sands would grow rapidly in the weeks after the war's end. Visitation in August and September 1945 (11,000) equalled prewar counts, and the monument that December recorded its busiest winter month since 1938. But the numbers also meant a strain upon scarce water resources (already threatened by continued military testing and the onset of drought in the basin). Then New Mexico's political leaders weighed in first with their calls for an atomic monument, and then their fears of the loss of hundreds of thousands of acres of grazing lands. One example of this concern was the idea of Charles S. McCollum of the Farm Security Administration in Las Cruces. He wished to make the test site "a real peace monument or shrine for the entire world." The crater could be fenced and equipped with a visitors center "that would be worthy of comparison with many of the fine buildings in Washington." McCollum would have deep wells drilled, and visitors drawn from around the world to experience both "the surrounding peacefulness of the desert calm," and "the terrible force that can be utilized against any nation that might have thoughts of making war on any other country."

Media attention also focused heavily on the Tularosa basin, with reporters scouring the countryside for evidence of the atomic test. Johnwill Faris kept a scrapbook of the famous visitors who came to the area , as the NPS collected information on the proposed monument. One such group included a reporter from the Los Angeles Times, who wrote of the publicity campaign waged by the Army to disprove Japanese charges of lingering health hazards at Hiroshima. "There was more radioactivity in the atomized New Mexico area visited by the newsmen," said the Times on September 12, "than possibly could have existed at Hiroshima because of the different altitudes at which the two bombs were exploded." As if to prove that Americans had nothing to fear from nuclear radiation, the Times portrayed prominent Manhattan Project officials walking through the cinders wearing "no protective clothing except canvas 'booties' where radioactivity would be 'hottest.'" The Army also allowed the media to take away as souvenirs the "atom-fused earth crust" which resembled "gray-green, crackled glass;" a compound later to be named "Trinitite."

For local boosters, the Times article proved the appeal of the test site to tourism, and by extension economic development. For the park service, however, the actions of the Army at the proving grounds soon indicated a bleaker future for a new monument in the Tularosa basin. On August 22, the War Department announced that it had transported from Europe two shiploads of German-made "V-2" rockets. Because of its vastness, the proving grounds would be the site of test firings for scientific research. The Army wanted to conduct these tests for 20 days at a time, with NPS personnel evacuated two days out of every three. U.S. Highway 70 would also be closed to traffic, thus limiting access for monument visitors. The Interior and War departments then negotiated a "Memorandum of Understanding," which included reimbursement to NPS staff for expenses incurred while away from White Sands. The superintendent at Carlsbad Caverns, Thomas Boles, expressed interest in employing Johnwill Faris and his staff if the White Sands closures were lengthy. This offer became moot in October 1945, when the Army decided to fire the V-2 rockets on four mornings per week, lodging the White Sands personnel overnight in Alamogordo.

The ultimate plan for test firings at the proving grounds did not stop Interior officials, New Mexican politicians, and the Alamogordo chamber of commerce from seeking high-level sponsorship of the atomic monument. Harold Ickes himself announced on September 8 that his General Land Office commissioner would "reserve the lands surrounding the place of the atomic bomb experiment for a new monument." Ickes wished to recognize not only the wisdom of using the bomb, saying that it "reduced the further loss of life and limb among members of the armed forces of this country and our allies." He also saw the monument portraying "the successful wedding of the skills and ingenuity of American, British and other scientists, and of American industry and labor." Then in a pronouncement that would symbolize the Cold War's fascination with nuclear power and energy, the Interior secretary declared: "The atomic bomb ushers in a new era in man's understanding of nature's forces and presages the use of atomic power . . . as an instrument through use in peace, for the creation of a better standard of living throughout the world."

Army Seals off the Trinity Site

Courtesy Los Alamos Photographic Laboratory

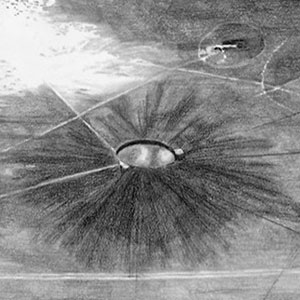

Ickes' directives put in motion a strategy of negotiation between the Interior and War departments that revealed the latter's commitment to national security versus the former's quest for historic preservation. E.T. Scoyen found it amusing that NPS headquarters had awarded $100 to a Mr. Joseph Stratton of the Chicago office for suggesting creation of the atomic monument. Scoyen noted that the first NPS employee to mention the concept was Johnwill Faris, and that his Santa Fe regional office had discussed the idea at length. More important was regional director Tolson's "adverse recommendation" of September 5. Publicity such as the Stratton award drew many curiosity-seekers to the Tularosa basin, and by October 11 Charles Richey reported that "quantities of the 'green glass' which supposedly lined the crater are being carried away." Within a month the Army had sealed off access to the Trinity Site, and even former NPS director Horace Albright could not gain permission to visit the prospective "monument."

For the remainder of 1945 , Johnwill Faris and his staff struggled with the past and future of White Sands. Large-circulation national magazines (Life and Look) sent photographers to prepare stories on the monument, and Harold Ickes asked the NPS to supply him with his own personal souvenirs of "trinitite." Regional director Tillotson had Faris collect specimens of the "green glass," along with a section of cable wire "that was actually used in transmitting the electric impulse which detonated the bomb." Tillotson warned that the souvenirs , while "tested for radioactivity," "should not be carried for any length of time in close proximity to the human skin." Secretary Ickes instead should keep the trinitite in "a glass or lucite container." Other applicants for atomic specimens were turned down, however, and NPS officials thus asked Faris to keep trinitite at White Sands for future display in the museum.

Johnwill Faris closed the momentous year of 1945 by negotiating a second memorandum of understanding with the Army Engineers on the monument's relationship to the "Ordcit" project. The Army not only had no plans to permit creation of an atomic park; it also persisted in its request for "intermittent use of the lands included in the White Sands National Monument within the exterior boundaries of the Ordcit Project." This assumption that Ordcit superseded the mandate of the park service became clear in the memorandum, as Faris agreed to remove all employees and close White Sands at the request of the War Department. In return, the Army would negotiate with all private grazing lease holders within the monument over the loss of access to their claims during test firings. The War Department would also reimburse White Sands staff for their expenses, house employees and their families at the Alamogordo air base at no cost, and pay for any damage to NPS lands and structures caused by Army missile testing.

The pattern of park management that unfolded from 1940-1945 would recur throughout the Cold War era. The military pressed Johnwill Faris in November to sign the memorandum without circulating it through proper NPS channels. The state of New Mexico kept up its demands for an atomic monument, and the local chamber of commerce churned out recommendations for improving the marketability of the Tularosa basin. One such suggestion came from L.A. Hendrix, mayor of Alamogordo, who wired the new Secretary of Agriculture, Clinton P. Anderson, requesting that the B-29 bomber that dropped the atomic device over Hiroshima be brought to town for display at the junction of U.S. Highways 70 and 54. Alamogordo boosters had already begun to describe their town as "the cradle spot of the release of atomic energy." Stimulating their interest was the temporary storage at the nearby Roswell air base (later renamed Walker AFB) of both the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombers. All this activity, plus the potential for vast increases in White Sands' visitation, led Johnwill Faris in December to ask NPS officials to change his status as a park service "custodian." Faris believed that his work at the dunes merited the more-prestigious (and better-paid) title of "superintendent." All that Hillory Tolson could advise from Chicago was that the park service distinction between "custodian" and "superintendent" was "arbitrary," having been "approved by high administrative field officials some years ago." Tolson knew of the awkward status of Faris and his monument within the park system, and hoped that "this explanation will enable you to enjoy more thoroughly and with some peace of mind the forthcoming holiday season."

Last updated: January 5, 2023