Last updated: November 4, 2018

Article

West Branch's Quaker Heritage

"The very name of the Quaker has become an instinct in the public mind of integrity, industry, and charity."

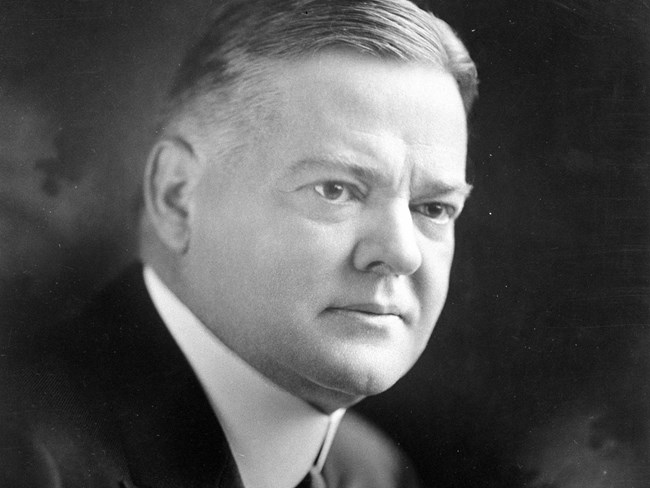

Herbert Hoover

Many of the values that steered Herbert Hoover throughout his long career as a statesman and public servant came from the Religious Society of Friends, or Quakers. The restored Friends Meetinghouse, where the future president and his family worshipped, represents the values of the community that shaped Herbert Hoover’s early years in West Branch.

National Archives & Records Administration

Integrity, Industry, & Charity

At the beginning of the First World War in 1914, Herbert Hoover, then a successful mining engineer in London, faced an important choice: continue his lucrative engineering work or accept an offer to head up a famine relief effort for Belgium. He wrote in his memoirs, “Mrs. Hoover and I spent a prayerful night, and next morning we concluded that duty called me to accept.”

Was this prayerful night the silent worship between two equal partners who searched their consciences and their souls for spiritual guidance? Only the Hoovers knew for sure. Of the Religious Society of Friends, Hoover wrote, “We have here a religious faith starting as a protest… bound together by no ritual, no symbolism, no creed, no clergy or bishop, no hierarchy. This religious faith… has never embraced more than a handful of people; it has suffered long periods of calumny and persecution, but in time it has come to enjoy a universality of high esteem… the very name of the Quaker has become an instinct in the public mind of integrity, industry, and charity.”

Who, then, were the Quakers, and how did their faith guide Herbert Hoover through his remarkable life journey?

NPS Photo by John Tobiason

Religious Society Of Friends

The Religious Society of Friends was founded in 17th century England by George Fox. Fox preached rejection of the hierarchy, dogma, and other “empty forms” of the established churches of his day. He believed that an element of God’s spirit is present in all human beings and that turning to the “Inner Light” in meditation allows direct communication with God for everyone without the intercession of clergy. He and his followers referred to themselves as “Friends of Truth,” or simply “Friends.” At their meetings Friends worshipped in silence waiting upon the Inner Light, speaking only when they felt moved by the Holy Spirit.

Friends believe that social action and worship have no dividing lines. In all aspects of life, they observe “testimonies” aimed at “right, plain living, in humble worship of God.” The testimonies are not written documents but shared understandings arising from the central idea that there is “that of God” in everyone, and each worshipper interprets them according to individual conscience. Friends’ main commitments are to the testimonies of simplicity, peace, honesty, service, and equality.

In the early days, the testimony to the equality of all people led Quakers to refuse to take off their hats in the presence of “superiors” and address everyone with thee and thou (the address of the common people) without regard to rank. They called for improved living conditions in prisons and worked for the protection of the mentally ill. The concern for honesty led Quakers to refuse to take oaths. Taking an oath implied different levels of truth, and they believed you should be completely truthful all the time. Friends are perhaps most widely known for the peace testimony. They consider violence in any form to be violence against “the Christ within” and refuse to go to war.

These differences caused frequent conflict with the English government, and Fox was often jailed. Once, when hauled into court, he suggested that the judge “quake and tremble at the word of the Lord.” The judge referred to Fox as a “quaker.” The nickname, once used in contempt, was adopted by Fox’s followers and has become the popular name for the Religious Society of Friends.

NPS Photo by John Tobiason

Meetings For Worship

Individual congregations are called meetings. Two meetings for worship were held during the week, on First Day and Fourth Day. Quakers referred to the days of the week and months of the year by numbers to avoid using names of pagan origin (such as Thursday, named for the Norse god Thor.) During Hoover’s boyhood, this was an unprogrammed meeting for worship, meaning there was no minister, no planned pattern for the service, and no music. Those who came to worship sat in “silent, expectant waiting” before the Lord. Any persons who felt moved by the Spirit to share their thoughts rose and spoke from their seats in the meeting. Those who spoke often and were acknowledged as being gifted in insight were recognized by being made recorded ministers.

Men and women sat apart, encouraging individual worship and full participation for women. Children attended the meetings also, boys sitting with the men and girls with the women. Once a month, men and women held separate monthly business meetings. Each Monthly Meeting belonged to an area Quarterly Meeting that met every three months. The Quarterly Meeting belonged in turn to a Yearly Meeting. Queries and advices printed from the Discipline of the Yearly Meeting were read at Monthly Meeting as reminders of the Friends’ insight and opportunities for self-examination. An example from the 1863 Discipline of Ohio Yearly Meeting (also used by Iowa Friends at the time): “Do Friends maintain love towards each other, as becomes our Christian profession? Are tale-bearing and detraction discouraged? And, when differences arise, are endeavors used speedily to end them?”

NPS Photo by John Tobiason

West Branch Meeting

Many of the early pioneers who settled in the West Branch area were members of the Religious Society of Friends. Both sets of Herbert Hoover’s grandparents were among these early settlers. His parents, Hulda and Jesse Hoover, met as young people growing up in the community. They married in 1870 and worshipped in the Friends Meetinghouse now located on the Herbert Hoover National Historic Site. The first Quaker settlers in West Branch met in members’ homes.

Quakers contributed to the construction of the first schoolhouse in 1853 and used it as their meetinghouse. By 1857 there were enough Quakers in town to build a separate meetinghouse on Downey Street, half a block north of Main Street. The new meetinghouse was simply furnished and decorated. Until 1883, the West Branch Quakers held twice-weekly unprogrammed meetings for worship.

Males and females sat on each side of an open partition, to encourage individual worship and full participation for women. Recorded ministers sat with elders and other respected members on the facing benches in the front of the building. Hulda Hoover, Herbert’s mother, was a recorded minister. The partitions were closed during the monthly meetings while membership business—marriages, deaths, births, new members, transfers, and disownment—was discussed. Infants and young children sat with their mothers. When infants disturbed the silence of the meeting their mothers took them to the nursery, or “cry room,” attached to the women’s side of the Meetinghouse. On the coal burning stoves, women heated soap stones which they used to warm their feet in cold weather.

Worshippers sat in “silent waiting” and spoke only when moved by an inner spirit. With the emphasis on individual worship, the meetinghouse had no pulpit or altar, no crucifixes or stained glass, nor an organ or a choir. “The long hours of meeting awaiting the spirit to move someone,” Hoover wrote, “may not have been recreation, but it was strong training in patience.” This training put to good use by a man who succeeded in business, fed millions in need, and presided over a nation in the early years of the Great Depression.